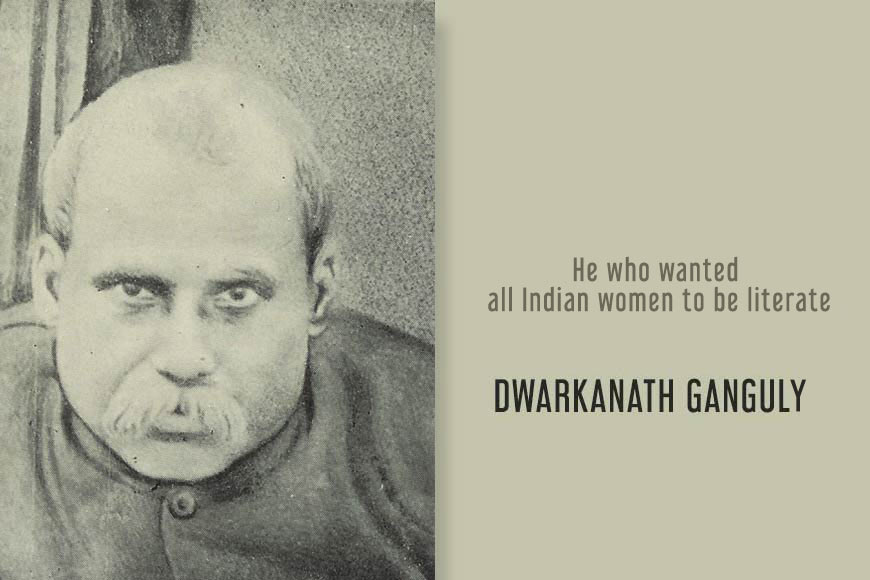

World’s first women’s liberation journal by Dwarkanath Ganguly, one who fought for women literacy

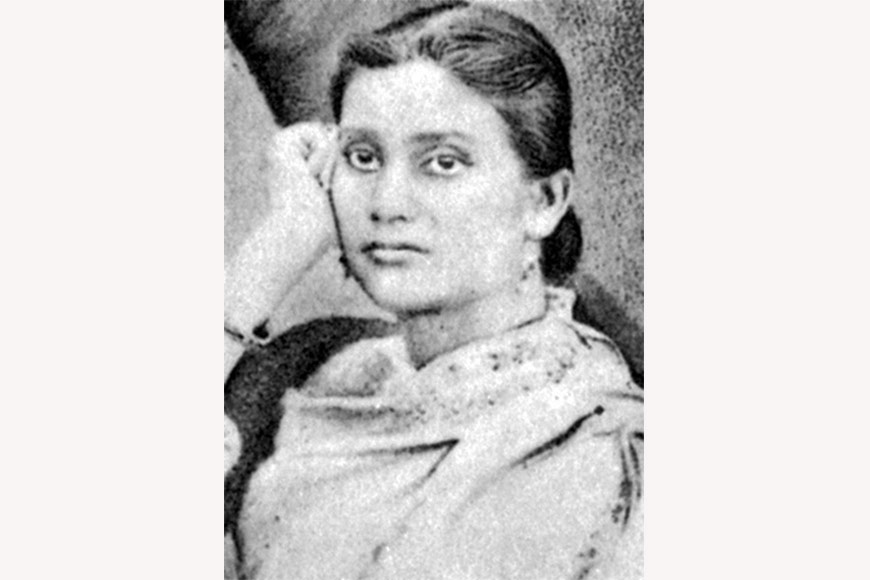

Many of us know of Kadambini Basu nee Ganguly, who was one of the first female graduates of India and later went on to study medicine and became one of the first female doctors of India too. But do we know there was a man behind this woman, who helped her in every step to achieve what she did, in an era and society when, women were still locked up in India behind a veil in the dark alleys of an Andarmahal?

Kadambini Ganguly

Kadambini Ganguly

As we say behind every successful man, there is a woman, behind every liberated woman in British India, there was a man. In this case it was Dwarkanath Ganguly, a schoolteacher in British-ruled Bengal of the late 19th-century. Dwarkanath was born in April 1845 at Magurkhanda village of Bikrampur in undivided Bengal. During his student life, he was deeply influenced by Akshay Kumar Datta’s thesis on the plight of Indian women that stated: ‘The first vital step to social regeneration is liberating woman from her bondage.’

This gave rise to an idea – publishing a weekly magazine called Abalabandhab (Friend of Women) through which he began bringing to light concrete cases of exploitation and the extreme suffering of women. Noted historian and professor emeritus at the University of Minnesota, David Kopf mentions in his book, ‘This journal by DwarkanathGanguly was probably first in the world devoted solely to the liberation of women.’

He was a Brahmo and as the Brahmo Samaj brought in the Bengal Renaissance, no wonder in his thoughts and beliefs, Dwarkanath was far ahead of his times. Apart from Abalabandhab, he also raised a storm within the Brahmo Samaj with his radical reformist views that were strongly opposed by the conservative members of the Brahmo movement. Dwarkanath was a learned teacher and served as the headmaster, teacher, maintenance man, guard and sweeper of Hindu Mahila Vidyalaya, the institution that was later merged with Bethune School). The soul aim of this school was to spread education among women.

Interestingly, when he married Kadambini Basu, she was a woman who wished to study. Dwarkanath gave his whole-hearted support to his wife and stood by her in thick and thin. Without her husband’s support she wouldn’t have been able to become one of the first female graduates of India. But when she wanted to study medicine --- a wing of education where no woman could even think of venturing, again she received her husband’s support. But the back lash from the then society was huge. Editor of the popular periodical Bangabasi referred to her as a courtesan. A furious Dwarkanath confronted the Editor and took legal action. As a result, the editor was sentenced to six months’ imprisonment and fined one hundred rupees.

That was a man behind a woman’s success. In an age when Indian society still reels under medieval ideologies of female foeticide, bride burning and dowry, it is so welcoming to know that Bengal had produced such liberal men long back in the 19th century who stood by their women and made them study.