Why we remember Franz Kafka on Safe Drive Save Life Day

On July 8, 2016, Hon'ble Chief Minister of West Bengal Mamata Banerjee launched the 'Safe Drive Save Life' campaign, intended to make our roads less prone to accidents. Relentless campaigning by the administration and police has had a great impact on the number of road accidents in the state, as statistics have shown.

As we observe 'Safe Drive Save Life' Day today, here's looking at an invention that has become one of the most critical components of road safety - the humble helmet - and the fascinating story behind its birth.

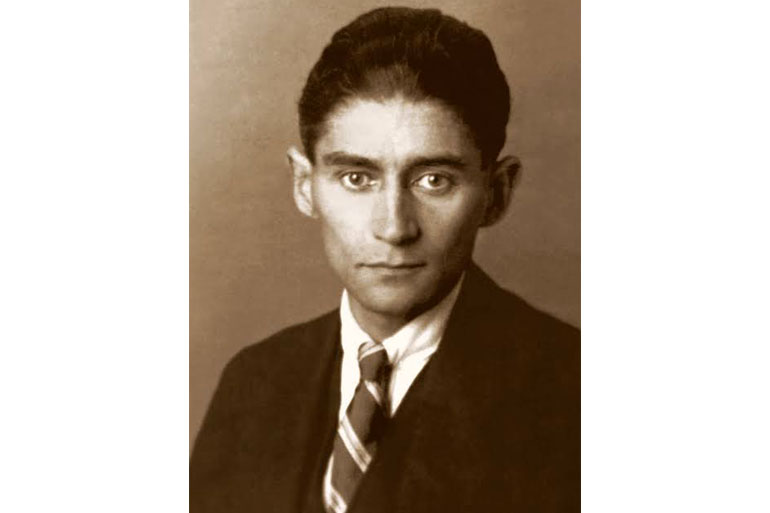

The story begins with Franz Kafka. Yes, the iconic writer and one of the most influential literary figures in history. But this is not an article about Kafka’s life or his writings. It is about Kafka, the employee of the Workers’ Accident Insurance Institute in the German kingdom of Bohemia, who in 1912 supposedly came up with something that has since saved countless lives in thousands of industrial and other kinds of accidents.

We are talking about the simple civilian helmet, or hard hat as the Americans call it, which management professor Peter Drucker credited Kafka with developing. In 1907, Kafka had joined an Italian insurance agency, but the long, tiring schedule left little time for his writing. He turned in his resignation within a year of joining and quickly found a new job with the Workers’ Accident Insurance Institute.

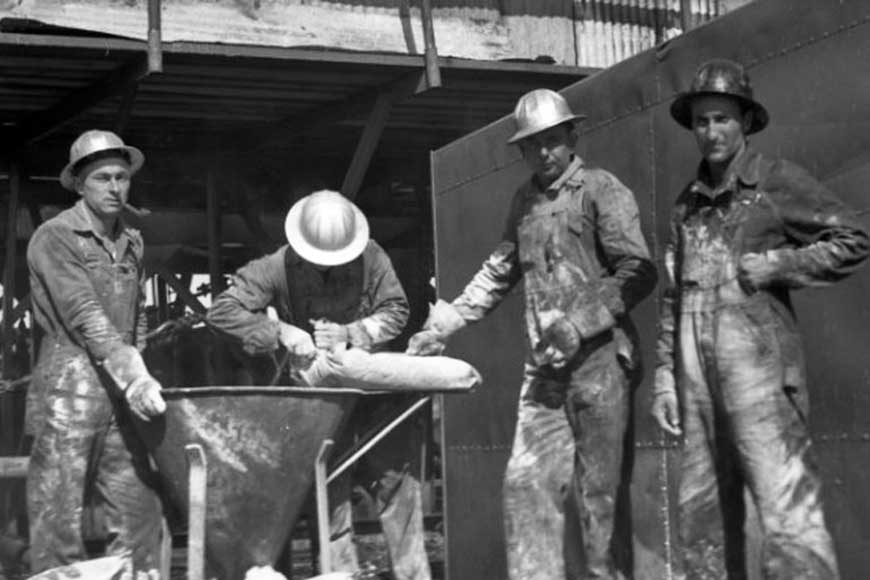

Those were the times when factory work was done manually, and fatal accidents were a common occurrence. Kafka’s job was to visit the accident site, assess the degree of injury, and fix compensation for the employee who had met with the accident. He was extremely efficient in his work and his employers paid him a hefty monthly salary that would amount to something like Rs 6 lakh, according to present-day valuations.

Franz Kafka, the man behind invention of safety helmet

Franz Kafka, the man behind invention of safety helmet

According to Professor Drucker, employers in those days had to cough up hefty sums as compensation to injured workers. To reduce employers’ losses, Kafka supposedly introduced a mandatory clause in the insurance contract, stating that all factory workers had to wear helmets while at work. This move worked like magic and the number of head-injury cases in factories reduced drastically. Kafka remained with the company until 1917, when a bout of tuberculosis forced him to take sick leave and eventually retire in 1922.

In his book, ‘The Exploding World of the Internet’, Drucker claims the American Safety Congress honoured Kafka with a gold medal in 1912 (tentatively) for introducing the safety helmet as a mandatory gadget in factories, a step which drastically reduced the number of injuries and insurance claims. Although there is no evidence from the company itself to substantiate this statement, Mashroor Arefin, a professional banker and business leader from Bangladesh who has been researching on Kafka for the past 20 years, claims many other authors who have worked on Kafka, including Stanley Corngold in his book ‘Franz Kafka: The Office Writings’, have substantiated this claim.

Kafka was asked by the government to join the military and go to the war front on two successive occasions, but when his employers came to know this they pleaded with the government to spare him because he was needed in the company. Kafka himself volunteered to join the army once but was rejected on health grounds. His failing health may have compelled him to leave his job but his employers magnanimously made provisions to pay him a hefty pension.

Today, when we see campaigns advocating the use of helmets in any field of life, such as Kolkata Traffic Police’s ‘Safe Drive Save Life’ campaign, or when we read of accidents that happened because motorcycle riders were without helmets, for instance, we should probably take off our hats to Franz Kafka, author extraordinaire and insurance man!