Why is Bishnupur not a UNESCO World Heritage site yet?

This is a story that goes back more than 20 years. With no satisfactory ending in sight as of now. And World Heritage Day (International Day For Monuments and Sites, to give it its proper name), celebrated every year on April 18, is a perfect opportunity to raise this question: why is Bishnupur, one of the ancient crown jewels of Bengal, not a UNESCO World Heritage Site yet?

If you visit the UNESCO World Heritage sites webpage, you will see a section marked ‘Tentative Lists’, containing 1,756 heritage structures from across the world, arranged according to countries listed in alphabetical order. The section for India contains 42 entries, one of which is ‘Temples at Bishnupur, West Bengal’, the only entry from the state. The date against this entry is 03/07/1998. In other words, since July 3, 1998, Bishnupur has been languishing on a ‘tentative’ list, which itself was last updated in 2019.

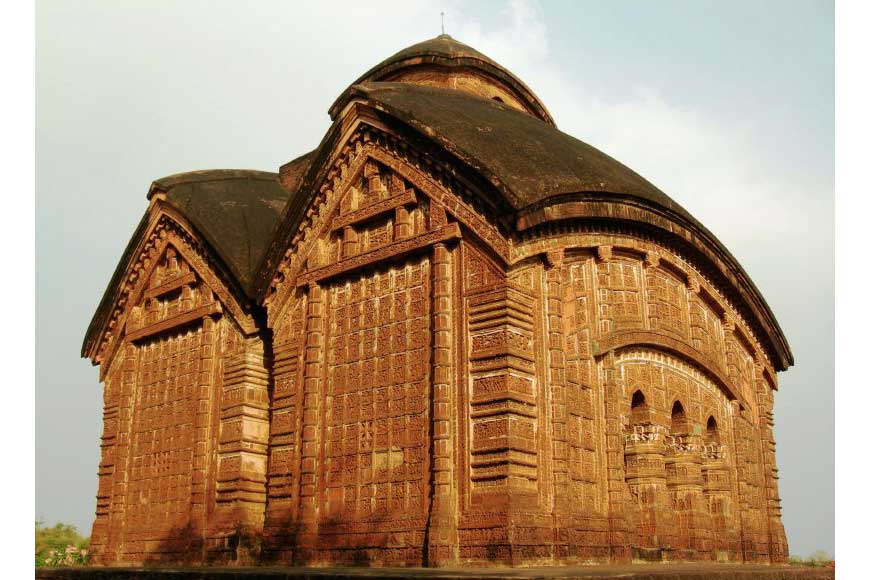

Jor Bangla Temple, Bishnupur

Jor Bangla Temple, Bishnupur

According to the webpage, the entry was submitted in 1998 by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), but astonishingly, not a single time does the word ‘terracotta’ come up in the description of these temples. And yet, the whole point of Bishnupur’s magnificent temples is that they were made of terracotta or burnt clay, a construction material practically unseen anywhere else in India when it comes to ancient structures.

All the eminent experts we spoke to - ranging from retired ASI director general Gautam Sengupta, to artist and West Bengal Heritage Commission chairman Shuvaprasanna, to art historian Debdutta Gupta, to conservation architect Anjan Mitra, to veteran journalist Indrajit Chowdhury - are of the view that the sheer diversity and richness of Bishnupur’s art and culture makes it worthy of the World Heritage tag. In fact, Mr Sengupta goes to the extent of saying that the absence of the tag “is a loss for world heritage”.

Baluchari Saree

Baluchari Saree

Indeed, not just terracotta temples, but terracotta pottery, artifacts, jewelry, and jars, ‘dokra’ metalcraft, bell metal ware, the famed Baluchari and Mallabhum saris made of tussar silk, the unique circular Dashavatar playing cards, and conch artifacts are just some of the other things that have made Bishnupur famous. All this is ‘tangible’ heritage, as Mr Gupta explains. As ‘intangible’ heritage, he points to the Bishnupur gharana, the only Indian classical music tradition to have originated in Bengal. “Add to that the rich local history, and the local myths associated with the Dalmadal cannon (the famed iron cannon reportedly used by the deity Madan Mohan in battle), and you have every component of a world heritage site,” he says.

Besides all of this, the city was the capital of the Malla dynasty of Mallabhum or Maalbhum (comprising Bankura, parts of Burdwan, Birbhum, Santhal Parganas, Medinipur and Purulia) for nearly 1,000 years, from the seventh century AD until the arrival of the British. As both Mr Mitra and Mr Sengupta point out, the water harvesting system which they instituted in a traditionally arid and drought-prone region was a remarkable and uncommon feat of urban planning.

Dashabatar Taash

Dashabatar Taash

So what exactly is the hold-up? Nobody seems to know for sure, but there have been sporadic efforts to move the matter along in the two decades since the entry was submitted. “The last time we interacted with UNESCO representatives, they told us that their focus was on more than one building or even a cluster of buildings. They were rather focusing on an entire area or ecosystem, such as the Sunderbans,” says Shuvaprasanna.

In other words, not just one temple complex, but an entire city would perhaps be more acceptable as a candidate for the World Heritage tag. Mr Mitra recalls a time in the early part of the 2000s when he and a few others in association with INTACH compiled a detailed dossier on Bishnupur as a world heritage city, where many of the ancient and medieval ways of life have continued into the present. In other words, living history.

Bishnupur Museum

Bishnupur Museum

“Bishnupur was a completely planted city, on a major trading route, and the Mallas, being fishermen by caste, realised the importance of water. The rainwater harvesting system that they instituted in such a dry area, using indigenous techniques, was so effective that the city could hold off even a decade-long Maratha siege,” he says. “It had the kind of eco-friendly layout that we strive to achieve even today.”

Conch Artifacts - Bishnupur

Conch Artifacts - Bishnupur

There was some talk that unauthorised commercial establishments adjoining the temple and palace complexes may have been a hindrance, but the experts say these technicalities can be sidestepped. The main problem, as more than one expert hinted, is ultimately “political” in nature. “UNESCO will only deal with what they call ‘state parties’, that is, nations. Therefore, what we call state governments cannot take up such an issue directly with them, it has to be routed through the Centre. Unless Centre and state work together jointly to push matters along, little can be done,” says Mr Sengupta.

Until then, Bishnupur, a medieval city almost certainly one of its kind in India, will continue to suffer the ‘tentative’ tag.