Why did the 18th century give birth to the modern Durga Puja?

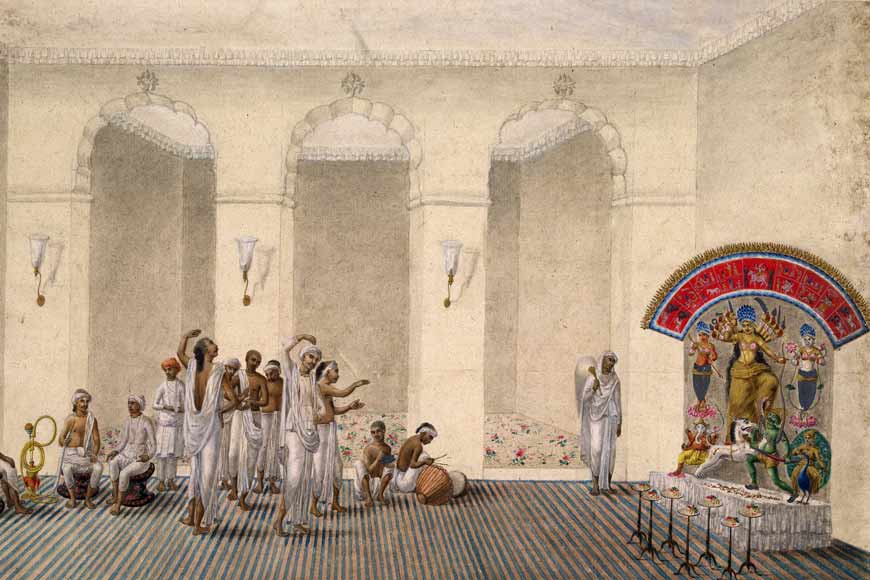

In its edition dated October 10, 1825, the English-language daily Bengal Hurkaru published a gushing eulogy to the Durga Puja at the residence of ‘Baboo Pron Kissen Holdor’ in Chinsurah. The residence, which apparently resembled a European mansion, had a huge salon on the ground floor where Puja guests would gather, amidst stunning furniture, a carpet imported from Brussels (Belgium), shimmering lights, tables groaning with delicacies, exotic singing and dancing girls, and even jokers and jugglers, the report added.

Can the modern day Durga Puja rival such extravagance? The ones held in traditional ‘bonedi’ (aristocratic) residences certainly no longer even come close. But do the ‘sarbojanin’ (public) pujas across Bengal replicate at least the lavish spending incurred by the erstwhile ‘babus’? With budgets running into several crores, the larger pujas certainly roll out the grandeur, but with theme pujas now almost de rigueur for most of them, the ‘art’ component of Durga Puja has probably become more important than a mere flaunting of wealth.

The babus were not held back by any such considerations. For Bengal’s aristocracy (whether by birth or by acquisition), Durga Puja was an occasion to put their wealth on full display, to impress both their peers and the ‘sahibs’, and “use the festival to demarcate and solidify their sense of identity and prestige”.

For a variety of reasons, the mid-17oos seem to be the time when Durga Puja really took hold of Bengal’s cultural space, following an initial surge in the late 1500s. Depending on which source you consult (British, Bengali, Nawabi), the explanations for this are contradictory, and the real reason is likely to be a combination of factors.

Who really held the first public Durga Puja in Bengal? Among the candidates are Kangsanarayaṇ, the zamindar of Tahirpur (now in Rajshahi district, Bangladesh) who held the Puja as a substitute for an ‘ashvamedha yajna’ (the Vedic horse sacrifice) when he succeeded to the zamindari in 1583; the Sabarna Roy Choudhury family, which granted the East India Company the land that eventually became Calcutta, and which first celebrated Durga Puja in 1610; Gobindaram Mitra (possibly died 1766), founder of the Mitra family of Kumortuli and one of the earliest babus of Calcutta, who held a lavish Puja in his house from the year he was appointed deputy collector in 1720; Raja Nabakrishna Deb (1733-97), founder of the Sovabazar Raj family, who presided over an elaborate Durga Puja in 1757 to hail the British victory at Plassey; and of course Raja Kṛishṇachandra Ray, zamindar of Nadia district from 1728-82, who instituted the public worship of Durga on a grand scale, exhorting his wealthier tenants to do likewise.

So why were these Pujas so important and extravagant? Some chroniclers say the lavish festival reflected a new climate of stability and opportunity under the British right around 1757, when the landed aristocracy finally dared show off their wealth and prestige, unlike earlier times when control rested with the Mughal representatives or nawabs.

These sources attribute much credit to “British tolerance and governing policies”, particularly Lord Cornwallis’ Permanent Settlement (1793), which determined taxes according to fixed landholdings instead of personal wealth. Indeed, in rural areas where the landed aristocracy managed to retain their wealth post-1757, and in Calcutta from the 1790s, there is abundant evidence of newly rich babus sponsoring grand Pujas as an indication of their growing social status.

As the Samachar Darpaṇ newspaper observed in 1829: “...those who became rich under British rule, in order to show off their wealth to those they ruled, cast aside their former fear and spent a lot of money on the Pujas.”

But there is an alternative explanation. According to these historians, it was the Mughal representatives and later the semi-independent nawabs who, prior to Plassey, brought sufficient prosperity and stability to the region to allow the flourishing of zamindari interests. Murshid Quli Khan, the first nawab to rule Bengal with some independence from the arm of Mughal control in Delhi, consciously attempted to support and even aggrandise large zamindaris like Burdwan, Birbhum, Bishnupur, Nadia, Dinajpur, and Natore.

This school of thought holds that after the coming of the British, the ability of the zamindars to patronise religious functions was severely hampered. As noted by historian John R. McLane, the abandonment by the British, and hence perforce by the zamindars, of the court ceremony at which dependents brought their revenues to the landlord and received robes of honour in return “signalled a retreat from symbolic to more purely contractual relations with [their] principal subjects”.

Moreover after Plassey, the British saw rural landowners purely as milch cows, breaking up their estates for revenue arrears, demilitarising their lands and making no allowances for revenue payments during the devastating famine of 1769-70. In 1758, Raja Krishnachandra, who had apparently helped the British to victory at Plassey, defaulted on Company payments. Under his grandson and great grandson, Ishwarchandra and Girishchandra, much of his Nadia property was sold, owing to revenue debts. The Burdwan zamindari under Tilakchand (1744-70), who welcomed the British in 1757, sank to its lowest levels by the time of the Bengal famine.

It was perhaps in this context that the ‘barowari puja’, or ‘puja sponsored by twelve friends’, was first introduced in 1790. Instead of the burden of expenses being borne by one family alone, the Puja was democratised, its costs spread out and shared among people not necessarily of the aristocracy. The sarbojanin pujas of today are heirs to this type of puja, bearing a legacy of riches to rags to riches.