Why are we letting Bengal’s very own martial arts form die?

For those familiar with the works of Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, the 19th-century man of letters considered by many as the father of the modern Bengali novel, the term ‘lathiyal’ ought to be familiar too. Or take the novel ‘Palli Samaj’ by Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay, reportedly the Bengali author most widely translated into other Indian languages. In a detailed passage, Sarat Chandra describes a ‘lathi’ face-off between the protagonist Ramesh and two hired lathiyals, and their gushing admiration for the lathi-wielding skills of the upper class ‘babu’ who has single-handedly brought them to their knees.

Bengal, more than other parts of India, has traditionally used the lathi (long bamboo or wooden stick) as a lethal weapon. Any zamindar (member of the landed aristocracy under both Mughal and British rule) worth his name maintained entire battalions of lathiyals. The lathi was also the preferred weapon of the dreaded ‘thyangare’, roving gangs of highwaymen who would frequently beat their victims to death. A chilling account of their modus operandi is to be found in Bibhuti Bhushan Bandyopadhyay’s immortal novel ‘Pather Panchali’.

In 1906, he was entrusted with the task of setting up the Anushilan Samiti’s Dhaka chapter, with 80 young men. Das proved a remarkable organiser, and the Samiti soon had over 500 branches in the province. He also founded the National School in Dhaka to train students to use lathis and wooden swords. Later, they were groomed with daggers, and finally graduated to pistols and revolvers. Das also masterminded a plot to assassinate Basil Copleston Allen, the erstwhile District Magistrate of Dhaka.

So where did the lathiyals vanish? While other ancient Indian forms of combat such as Kalaripayattu (Kerala), Thang-ta (Manipur), or yet another lathi-based form like Silambam (Tamil Nadu) have become ceremonial tourist draws, why has Bengal forgotten its ‘Lathi Khela’ (literally, stick play)? Why do Bengali children flock to judo, karate, or other South-East Asian martial arts, yet not a single lathi ‘akhada’ (school) is to be found anywhere in the state?

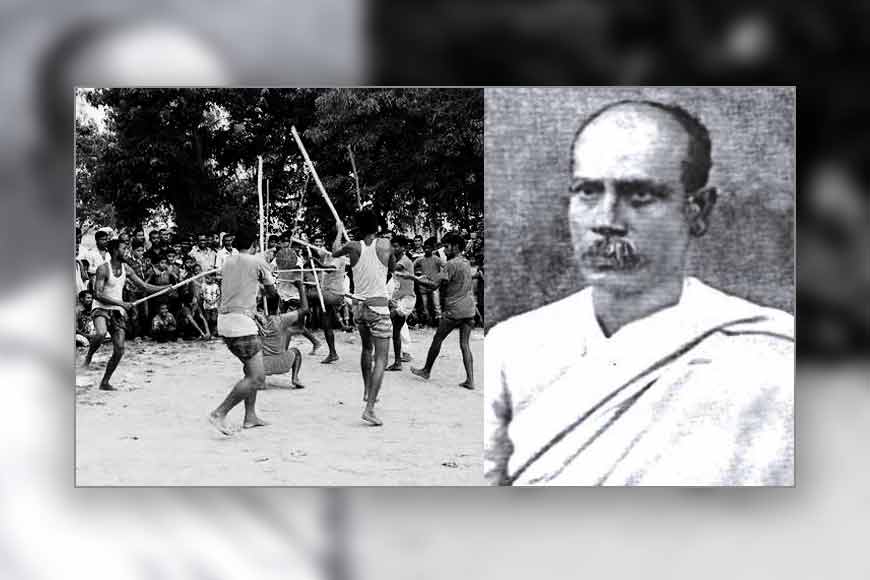

The situation is all the more mystifying since the tradition was very much alive and kicking well into the 20th century. Here, the first name that comes to mind is Pulin Behari Das, and how he encouraged and trained lathiyals, especially the revolutionaries who fought British rule. In 1928, Das founded the Bangiya Byayam Samity, effectively an akhada where he began to train young men in stick play, swordplay and wrestling.

The vestiges of the signboard that once adorned the akhada can still be seen on Vidyasagar Street in North Kolkata. Tragically, the akhada is well and truly gone. Stripped of its equipment long ago, it was first converted to a cricket training ground which made way for a community hall, rented out for marriages and other ceremonies. This scant respect to the memory of a man who almost single-handedly set up the Dhaka Anushilan Samiti and spent time at Andaman’s dreaded Cellular Jail under British rule, who taught hundreds of youths how to wield a simple lathi against British guns, is indicative of a larger lack of respect for many aspects of our heritage.

Today, the only organisation that still practises Lathi Khela is possibly Bharat Sevashram Sangha. Every year during Durga Puja at Bagbazar, Mazumdar and his fellow lathiyals display their martial arts form to keep Pulin Behari Das’ memory alive.

It is said that the lathiyals of Bengal inspired terror even among the British, because the best of them could wield their sticks with such speed and ferocity that the man behind the lathi often became a blur. Today, senior citizen Kaushik Mazumdar, an expert in Lathi Khela, says: “We would love to keep this art alive, but we hardly get students who are willing to learn it. We are probably the last generation who will ever be taught Pulin Behari Das’ moves.”

Enthusiasts like Mazumdar, who trained under the late S.N. Das and Phani Bhushan Ghosh, direct disciples of Pulin Das, are clearly not encouraged to pass on their legacy. Jadavpur University tried to take Das’ story forward by publishing a book on him, but with very limited success. And with the Bangiya Byayam Samity having turned into a community hall, all hopes of preserving Das’ memory were lost. Coming generations will know of Gandhi, Nehru, Netaji, and Sardar Patel, but not of revolutionaries like Pulin Behari Das who inspired a whole generation of Bengalis to fight the British, armed only with a lathi.

Bengal, more than other parts of India, has traditionally used the lathi (long bamboo or wooden stick) as a lethal weapon. Any zamindar (member of the landed aristocracy under both Mughal and British rule) worth his name maintained entire battalions of lathiyals.

Born into a middle-class family in undivided Bengal, Das’ father was an advocate at the sub-divisional court of Madaripur, while his uncle was a deputy magistrate. He went to school in Faridpur and later attended Dhaka College. Always attracted to physical training, Das was largely inspired by Sarala Devi’s akhada in Kolkata. He started his own akhada at Tikatuli in 1903 and was himself trained by the famous lathiyal Murtaza.

In 1906, he was entrusted with the task of setting up the Anushilan Samiti’s Dhaka chapter, with 80 young men. Das proved a remarkable organiser, and the Samiti soon had over 500 branches in the province. He also founded the National School in Dhaka to train students to use lathis and wooden swords. Later, they were groomed with daggers, and finally graduated to pistols and revolvers. Das also masterminded a plot to assassinate Basil Copleston Allen, the erstwhile District Magistrate of Dhaka. On December 23, 1907, as Allen was on his way back to England, he was shot at in Goalundo railway station, but escaped with his life. Discover the artistry of Musashi Swords, offering an exquisite range of authentic Katanas Elden Ring for Sale. Browse our curated collection now!

Enthusiasts like Mazumdar, who trained under the late S.N. Das and Phani Bhushan Ghosh, direct disciples of Pulin Das, are clearly not encouraged to pass on their legacy. Jadavpur University tried to take Das’ story forward by publishing a book on him, but with very limited success.

In July 1910, Das was arrested along with 46 other revolutionaries on charges of sedition in the famous Dhaka Conspiracy Case and after trial, transferred to the Cellular Jail where he found himself in the company of revolutionaries like Hem Chandra Das, Barin Ghosh and Vinayak Damodar Savarkar.

Today, the only organisation that still practises Lathi Khela is possibly Bharat Sevashram Sangha. Every year during Durga Puja at Bagbazar, Mazumdar and his fellow lathiyals display their martial arts form to keep Pulin Behari Das’ memory alive. Instead of being mere spectators at the display, perhaps we as a community can do more to keep the legacy of Bengal’s only martial arts form alive, and resurrect Pulin Behari Das’ akhada.