When two planets were engaged in a chat – why Tagore and Einstein never agreed?

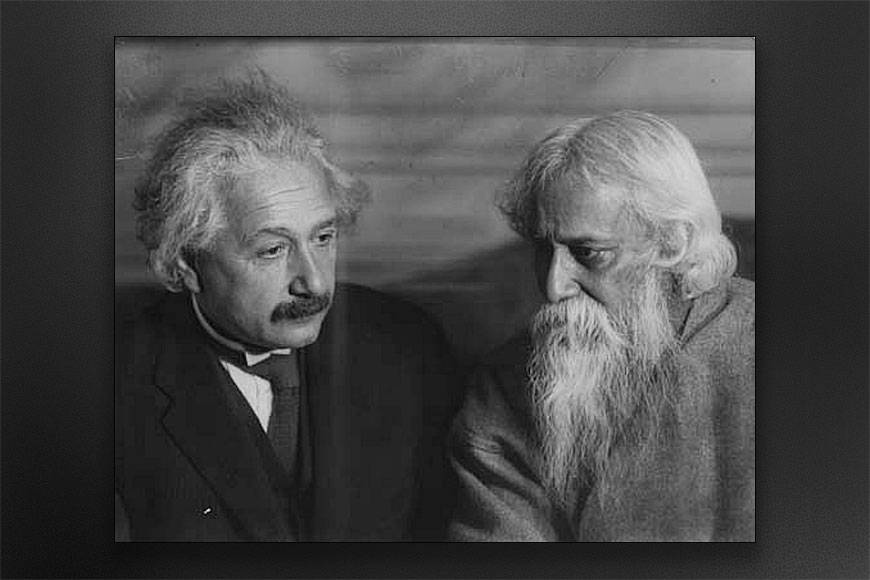

When a poet meets a scientist, sparks flow down the intellectual universe and that’s exactly what transpired between Rabindranath Tagore and Albert Einstein when they met a couple of times. However, the twain never met in minds, probably because of their diverse thought processes on a larger consciousness controlling the universe that somehow defied Einstein’s scientific knowledge. During times when disease and fury of nature seem to be ravaging mankind even in the 21st century when man thought he had already been successful in reining in nature, such conversations throw up the dichotomy between philosophy and science.

Einstein later termed his conversation with Tagore as ‘rather unsuccessful because of difficulties of communication.’ But three months later, in October, he contributed to a Festschrift for Tagore’s seventieth birthday, The Golden Book of Tagore (1931). It is said that Tagore declined an offer of an honorary doctorate from Berlin University in protest against the Nazi treatment of Einstein.

Of all the Jews Tagore made friends with, it was his friendship with Albert Einstein which made international news in a big way. It was Tagore’s dialogue with him that came to be written about extensively. Tagore met Albert Einstein a number of times; the first being during his second visit to Germany in 1926. But Einstein was certainly aware of Tagore by 1919 (or even earlier), for they had signed together an anti-war ‘Declaration of the Independence of Spirit’. Their conversation in 1926 was not recorded, but the conversations that followed in 1930 when they met four times were, the earlier two of which were published: the first one (that on 14th July) in the New York Times on 10th August, the second (that on 19th August) in the New York-based magazine Asia (March 1931). Although both conversations concerned science, yet the first one, which was focused on reality, came to be considered as the more significant and was reported under the heading “Einstein and Tagore Plumb the Truth.”

And what was written in it?

It was interesting to see them together – Tagore, the poet with the head of a thinker, and Einstein, the thinker with the head of a poet…Neither sought to press his opinion. They simply exchanged ideas. But it seemed to an observer as though two planets were engaged in a chat.

Einstein later termed his conversation with Tagore as ‘rather unsuccessful because of difficulties of communication.’ But three months later, in October, he contributed to a Festschrift for Tagore’s seventieth birthday, The Golden Book of Tagore (1931). It is said that Tagore declined an offer of an honorary doctorate from Berlin University in protest against the Nazi treatment of Einstein. He also voiced his protest against Einstein’s ill-treatment by the Nazis, a protest which found its way into newspapers. In a letter from 1934, addressed to N E B Ezra, editor of the Israel Messenger, Tagore wrote:

‘…if the brutalities we read of are authentic, then no civilized conscience can allow compromise with them. The insults offered to my friend Einstein have shocked me to the point of torturing my faith in modern civilization.’

However, scholars have come to recognize the roots of the lack of philosophical communication between the two as much deeper than a mere linguistic barrier, as illustrated by what the philosopher Isaiah Berlin, who attended Tagore’s Oxford lectures, commented in 1993:

‘I do not believe that, apart from professions of mutual regard and the fact that Einstein and Tagore were both sincere and highly gifted and idealistic thinkers, there was much in common between them – although their social ideals may well have been very similar. Einstein could never agree with Tagore’s concept of a universal mind controlling nature, because of his commitment to the realism, determinism, and strict causality of classical physics.’

Tagore met Albert Einstein a number of times; the first being during his second visit to Germany in 1926. But Einstein was certainly aware of Tagore by 1919 (or even earlier), for they had signed together an anti-war ‘Declaration of the Independence of Spirit’.

Tagore wrote: ‘The Universe is like a cobweb and minds are spiders; for mind is one as well as many.’ Tagore was of the view that nature could be conceived only in terms of our mental consciousness for what we perceive is subject to what we think. In his words: ‘The world is a human world – the scientific view of it is also that of the scientific man… What we call truth lies in the rational harmony between the subjective and objective aspects of reality, both of which belong to the super-personal man…if there by any truth absolutely unrelated to humanity, then for us it is absolutely non-existing.’

In contrast to Tagore, Einstein held the view that nature exists, objectively, irrespective of our awareness of it. Hence, he thought, it was necessary to describe “what nature does”, rather than just speaking about our knowledge of nature.