When the Statesman refused to publish Tagore’s letter – GetBengal story

“The time has come when badges of honour make our shame glaring in the incongruous context of humiliation, and I for my part wish to stand, shorn of all special distinctions, by the side of those of my countrymen, who, for their so-called insignificance, are liable to suffer degradation not fit for human beings.”

Thus runs an extract from the letter which Rabindranath Tagore wrote renouncing his British knighthood following the 1919 Jallianwala Bagh massacre, a letter that has become the stuff of legend, showing as it does the angry protester behind the mild-mannered, benign poet.

A dozen years later, however, he wrote another letter that is not quoted as often, one which was far angrier and harsher in tone than his earlier effort. On October 13, 1931, as he was preparing to leave for Darjeeling to recover from ill health, Tagore received news of the Hijli firing, in which British police shot and killed two young unarmed detainees, Santosh Kumar Mitra and Tarakeswar Sengupta, at the Hijli detention camp on September 16, 1931.

The incident occurred when police surrounded the camp, got into an altercation with detainees, and finally opened fire, shooting Mitra in the abdomen and Sengupta in the forehead.

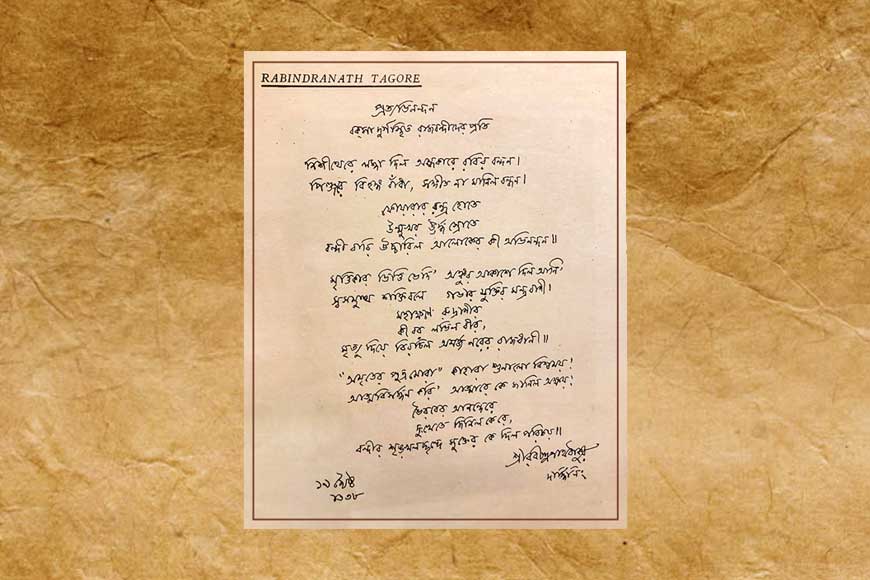

As public outrage over the incident grew, Tagore lent his own furious voice to that of millions of fellow Indians in a letter written from Darjeeling, dated November 2, 1931 and addressed to the Statesman, then edited by Alfred H. Watson. “We have recently seen in an Anglo-Indian paper repeated expressions of the Christian sentiment of sympathy for the warders who had under their charge the prisoners at Hijli whom they murdered,” the letter began.

In the same paragraph, castigating the attempts to pass off the firing as a result of the “nervous strain” felt by the warders, he wrote, “These high-strung individuals – who enjoy freedom and self-respect and live in comfortable barracks – have been soothed with paragraphs of tender consideration for their concerted homicidal attack, under cover of darkness, on defenceless prisoners undergoing the most barbaric system of incarceration and a nerve-racking strain of an indefinitely suspended fate.”

This was Tagore shedding his reserve, the outraged Indian emerging from within the refined global citizen, all guns blazing, challenging the hypocrisy of a so-called civilised government. Small wonder, then, that Watson refused to print the letter, returning it to Amal Home – the editor of the gazette from which this piece is sourced, and the man who had forwarded the letter to Watson on Tagore’s behalf.

“I must definitely refuse to publish from Dr. Rabindranath Tagore or anybody else a letter which accuses men of murder who have never been tried on that count. I return the letter to you,” Watson wrote to Home.

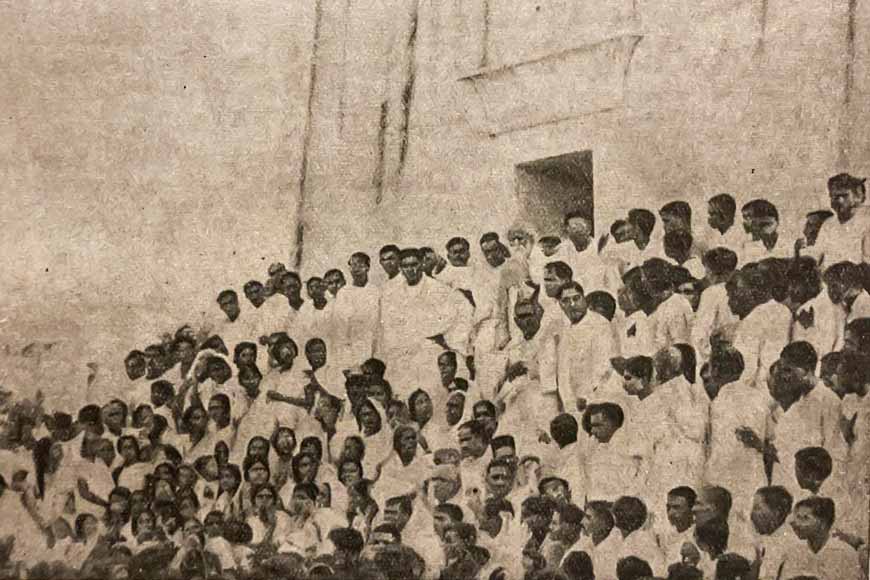

Fortunately, the unpublished letter has been preserved for posterity, its contents publicly disseminated a few days before Watson’s churlish gesture of refusal. Before leaving for Darjeeling in October 1931, Tagore spearheaded a public meeting at Town Hall in protest against the firing, and people turned up in such huge numbers that the venue had to be shifted to the Maidan at the foot of Shahid Minar (then called Ochterlony Monument).

With renowned lawyer and freedom fighter Jatindra Mohan Sengupta by his side, Tagore read out his letter to the huge gathering, imprinting upon the government’s collective consciousness the anger, shock, and outrage felt by the common citizen. In the end, the fact that the Statesman didn’t find the letter suitable for publishing mattered little.

Significantly, the letter also advised restraint for both ruler and ruled, advocating a stop to the endless cycle of violence which, Tagore felt, damaged both sides of the argument. “Giving vent to one’s anger and annoyance may be natural to common humanity but it is never statesmanlike for our rulers nor wise for the ruled,” he wrote.

In troubled times like our own, those words seem uncannily relevant.

Source: Calcutta Municipal Corporation Gazette’s Tagore Memorial Special Supplement, published September 13, 1941