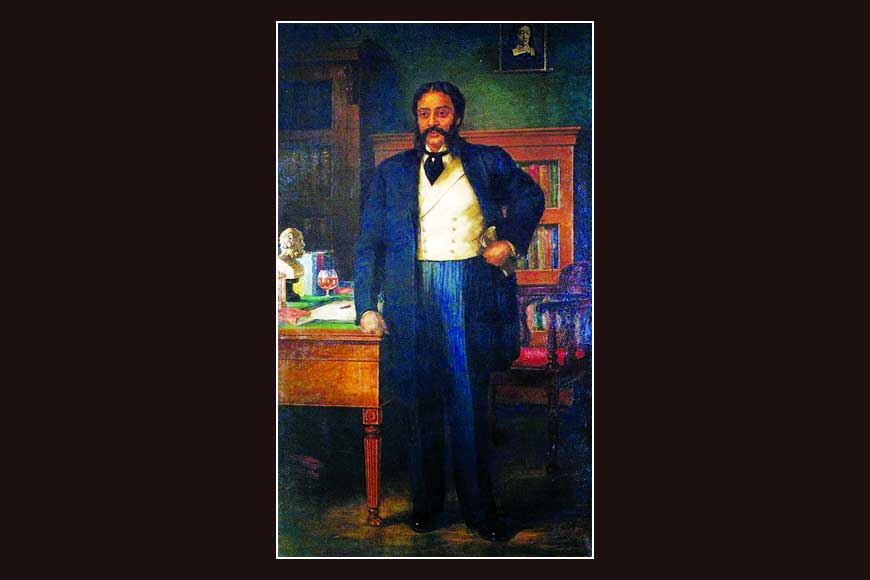

What have we done beyond paying lip service to Michael Madhusudan Dutt?

Michael Madhusudan Dutt, who died in 1873 on today’s date in Calcutta at the age of 49, spent most of his early life wanting to be an ‘English’ poet, and trying very hard to become one since he was 17. A popular story goes that the renowned Anglo-Indian educationist John Drinkwater Bethune finally told Michael Madhusudan Dutt that he ought to “employ his time to better advantage than writing English poetry”, suggesting that he write in Bengali (Bangla) instead.

Trouble was, Michael simply didn’t know enough Bangla to create literary works in the language. To the extent that a well-established though possibly apocryphal joke has it that, in his quest to create a literary masterpiece, Michael would employ Bengali pundits to supply him with the perfect Bengali synonym for an English word, which would then be used in the work.

Jokes apart, however, the journey from an anglicised, aspiring master of English poetry to one of Bengal’s literary giants has remained largely absent from the public radar, despite the plethora of works on Michael and his genius. Who would have believed that the young man who was so hell-bent on going to England that he went against his wealthy, conservative father Rajnarayan and entire family, converting to Christianity in defiance of every social taboo, would also create the first original play in Bengali?

In a way, Michael was a ‘post-colonial writer’ before the phrase even existed. In one of life’s poetic ironies, his stay in London as he studied to become a barrister at Gray’s Inn so thoroughly disillusioned him about European culture that he was to write to his friend Gourdas Bysack from France: “If there be any one among us anxious to leave a name behind him, and not pass away into oblivion like a brute, let him devote himself to his mother-tongue. That is his legitimate sphere, his proper element.” This, from a man who was a gifted polyglot, able to speak and write in at least eight languages.

But this is not to repeat what many others have said about Michael and his writings, or the stories of his turbulent, unsettled, tragic life. This is to point out how little we have actually remembered, of our mere lip service to his name, of our disrespect to the only tangible heritage we have left to us: the two-storeyed Dutt mansion in Kolkata’s Khidirpur. Originally bought by Rajnarayan in 1800 as his legal career prospered and grew, the house stands at 20B, Karl Marx Sarani, where young Michael began living in 1833 or 34, and it was from here that he joined Hindu (later Presidency) College, simultaneously stepping into the literary universe.

Once he converted to Christianity in 1843, however, his stay at the house ended. He did come back once after his mother’s death, and then inherited the house for good once his father died in 1855, returning to Calcutta from Madras in 1856. Forced to fight for possession of the house against conniving relatives, he finally won the legal battle in 1861. But he was still entranced by his dreams of life in Europe, and sold off the ancestral property for a mere Rs 7,000 (not more than Rs 70,000 today) to raise funds for his trip abroad.

Since then, numerous changes in ownership, additions and deletions to the original palatial Indo-Western structure, have made the house almost unrecognisable. Hidden away among the surrounding structures, its small courtyard a fraction of what it used to be, it is festooned by a veritable forest of electrical wiring, through which the old beams still try to peep. Among the building’s current tenants are multiple small offices, a few residents on the first floor, and some Fancy Market warehouses. The remaining portions are largely uninhabitable.

Michael's birthplace in Sagardari

Michael's birthplace in Sagardari

Compare this to how lovingly Bangladesh has maintained the home of his birth at Sagardari, in modern day Jessore district. Every year on his birthday on January 25, a fair is held in his home, organised by the District Council of Jessore and attended by several MPs and ministers. A school and a college have already been named after him in Jessore, and a university is proposed to be set up at his birthplace.

Michael Madhusudan Dutt's Kidderpore house

Michael Madhusudan Dutt's Kidderpore house

By contrast, though reportedly an officially declared heritage structure, the Kolkata Corporation apparently possesses no records that link the Khidirpur house to Michael and his family. The present owner apparently wishes to convert the building to a shopping mall, and has sought legal help to take it off the heritage list. Tragically, nobody can say with any certainty that this will never happen.