War of letters between Satyajit Ray and Mrinal Sen

Let’s start with words and not with movie dialogues…. Let’s start with letters….

Satyajit Ray: ‘May I point out that the topicality of the theme in question stretches back into antiquity, when it found expression in that touching fable about the poor deluded crow with a fatal weakness for status symbols?’

Mrinal Sen: ‘To conclude, I do not, by any chance, wish to take refuge under the fabled crow's wings and claim to be an Aesop or a Cervantes or Chaplin. I have made a film called Akash Kusum and that is all’

Satyajit Ray: ‘A crow film is a crow film is a crow film’ (paraphrasing the French filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard)

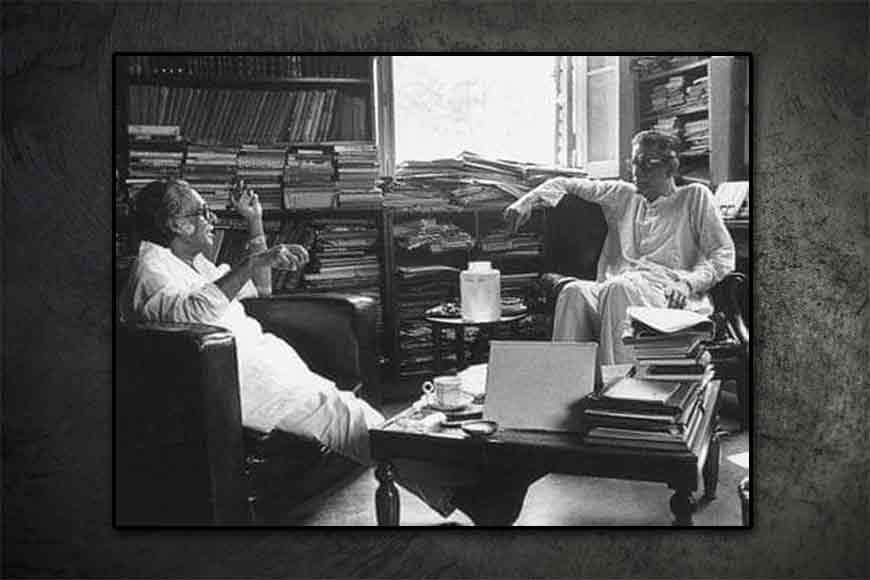

The war of words and ideology did not end here. Over a span of a month in 1965, The Statesman carried letter after letter by two of the most celebrated directors from Bengal, Satyajit Ray and Mrinal Sen. Their wit dragged names such as Cervantes, Aesop, Ibsen, Gorky, Wilde and even Hamlet and also exposed how different they were in their views and ideology.

However, the rivalry between Sen and Ray remained restricted to ideology only and in real life they had a mutual respect for each other, gifting India internationally acclaimed movies through their unorthodox approach and analysis of political and social issues. Their ways were different but powerful in their exposure and subtlety. Mrinal Sen himself knew of this difference and also how Ray’s films had a bigger mass appeal than his. But like a pragmatic director Sen had once said: “It is up to each communicator to choose his or her own shade of grey. After all, there is no black and white in the real world.”

Mrinal Sen happened to be a filmmaker by chance. He earned a post-graduate degree in physics from Calcutta University, when one day he came across a book on film aesthetics by Rudolf Arnheim. The book changed the direction of his life and he went on to become a part of the New Wave of Indian cinema with Satyajit Ray and Ritwik Ghatak on the other end of the same movement.

Of the three, Ray and Sen shared the longest rivalry. Ghatak’s sudden death in 1976 led to some recalibration of their chemistry. But at heart, they remained fierce competitors. As Sandip Ray, Satyajit Ray’s son, had once said in an interview: “You cannot perform in a vacuum. Only when you have stiff competition do you have the urge to excel. Mrinal Sen and Ritwik Ghatak’s presence naturally urged my father to outshine himself. I am sure that my father’s presence had a similar effect on them.”

Mrinal Sen’s movies had a rebellious expression, may be bringing out the political activism, of which he was a part of since his student life. Such debates on political economics are reflected in movies Interview (1971), Calcutta 71 (1971) and Padatik (1973). His activism was on the face, he used his camera and visual treats as a weapon against oppression and social stigma. Sen was thus audacious in just speaking the language of protest, sending the ideological signals straight through the audience, instead of trying to express the same through subtle dialogues and story-telling. In an interview to Cinestaan, another filmmaker Shyam Benegal had once acknowledged “Mrinal made political statements and was very open about where he stood.”

A lifelong member of the Communist Party of India, Mrinal Sen never took politics lightly. Along with Ghatak, he shaped politically conscious cinema for the Indian audience. Yet, he possessed the gift of cinematic technique and deviated from the narrative form. Take for example his movie Interview, where the protagonist (played by Ranjit Mullick) in a running tram suddenly breaks the sacred fourth wall and indulges in a conversation with the crowd in the tram. This style defined Mrinal Sen. He experimented with all sorts of storytelling and styles. Chorus, another movie stands out as a reverse allegory, with the workings of heaven described as a bourgeois society.

And Sen did these experiments very consciously. In 2000, he wrote: “My question is a very vital one: whom do I, the communicator, address? The metropolitan variety or the rural masses? Which vocabulary, and going further, which wavelength, as a necessary adjunct, do I choose? To work out an ideal situation, should I try a middle path — both in terms of words and images, and in terms of attitudes? In other words, do I have no choice but to compromise?... All these are likely to raise diverse issues on the aesthetic front with hardly any easy solution. Or, can such a debate as I envisage lead to any tangible conclusion? I wonder.”

Probably, Sen had kept debating on this confusion of a director till his last breath. And as generations will watch his path-breaking movies like Bhuvan Shome (1969), Oka Oorie Katha (1977, based on Premchand's ‘Kafan’) or Mithun Chakraborty in Mrigayaa (1976), Sen will be lying in Peace House, waiting for his cremation on the first day of the New Year.