Vanishing tribe of Kadma – Bengal’s own candy makers

That gooey and sugary yellow swan or the pink tomb that stood atop a puja prasad in our childhood days, often attracted children and their taste buds more than the humble batasha did. So were the pristine white Kadma, that needed a really strong tooth to break. Kadma has been the indigenous sweet of Bengal that was once an inseparable part of Kali Pujo, Saraswati Pujo, Ratha Yatra (chariot festival) and Nabobarsho (Bengali New Year). Although this sweet is easily available in grocery shops and is sold round the year, its demand skyrockets during these festivals. In many parts of Bangladesh (erstwhile East Bengal) this sweet is known as ‘Tilua.’ The dry sweet resembles a ‘Kadam flower’ (Neolamarckia cadamba or burflower-tree, laran, and Leichhardt pine, an evergreen, tropical tree native to South and Southeast Asia) from where it derives its name. The inside of the sweet is hollow and its top and bottom ends are slightly pressed inside like an orange.

The pristine white Kadma is made of sugar and looks really impressive. According to the demand or requirement in the market, sweetmeat makers change the size of kadma from a diameter of 1 cm to even 10 or 15 cms. Made of sugar, jaggery and sometimes with powdered roasted nuts, colourful kadma shaped like different animals and birds, is very popular with children across India. On the eve of Poila Baishakh (Bengali New Year), local grocery stores sell heaps of Kadma or sugary candies, shaped like swans, parrots, hens, horses, temples and many more, in pinks, whites and yellows.

Kadma is also a very popular sweetmeat of Andhra Pradesh. It is a traditional sweet there and is called ‘Panchadara Chilakalu’. In Telugu, ‘Panchadara’ means sugar and ‘Chilakalu’ means parrot. Hence the traditional sweet, which is in demand during Makar Sankranti, a harvest festival celebrated in the month of January, is shaped like a parrot usually. It is made by pouring thick sugar syrup in parrot shaped wooden moulds.

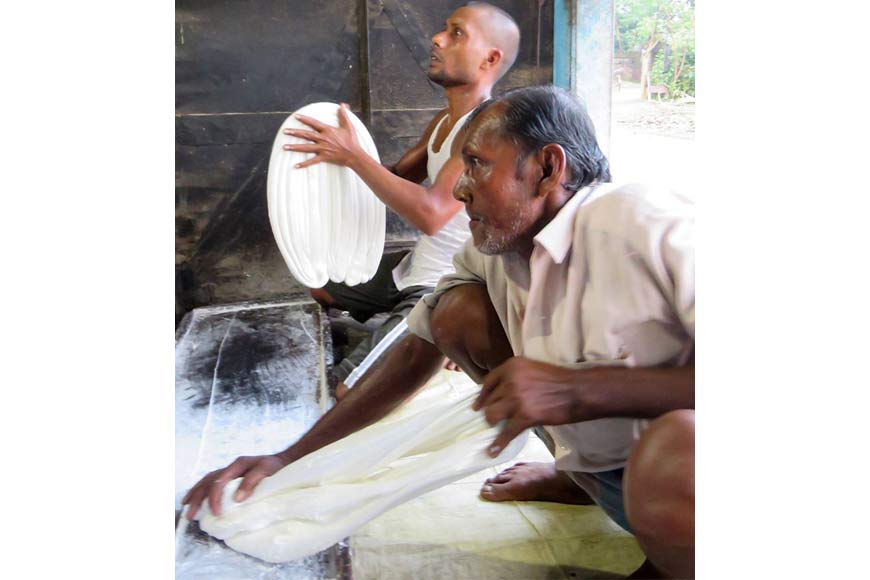

The Kadma making process is quite complicated and laborious. To begin with, sugar is boiled in water and then the syrup is poured on a flat surface and allowed to cool. Icing sugar is added to the surface and more syrup is poured and then before the second layer of syrup crystallizes, it is rolled and tied to a pole and stretched. After a while, the rolled sugar is folded again and pulled and stretched. This process is repeated several times and the brown colour of the syrup changes to white gradually and the inside of the rolled sugar strip becomes hollow. The sugar strip is then placed on a board and again sprinkled with icing sugar. Finally, the strip is placed in the kadma maker machine or mould and diced according to requirement and then air dried to a crispy white perfection.

It is a traditional ritual to have Kadma during Poush Sankranti aka Makar Sankranti. Kadma is also an integral part of Kali Puja. It is a very old custom to offer Kadma as ‘Prasad’ (a devotional offering made to Goddess Kali) and competitions are held between rival organizers to offer giant Kadma to the deity.

In North Bengal, Manindranagar Gram Panchayat area of Bahrampur is a Kadma making hub. Similarly, Mankar in East Burdwan district and Nabadweep in Nadia district are renowned for the crispy, chalk-white Kadma. Usually, 10 to 15 kgs of sugar is required daily to keep an uninterrupted supply of Kadma to the state’s markets. However, of late, the sweetmeat has lost much of its charm due to lack of competent craftsmen and the young generation’s lack of interest to continue in the trade. The gradual shift in food habits of the masses has further added to the woe of this indigenous sweet and it is losing ground to more fancy desserts and sweetmeats like chocolates and pastries and fusion sweets.

Image Courtesy : https://www.kramabardhaman.com