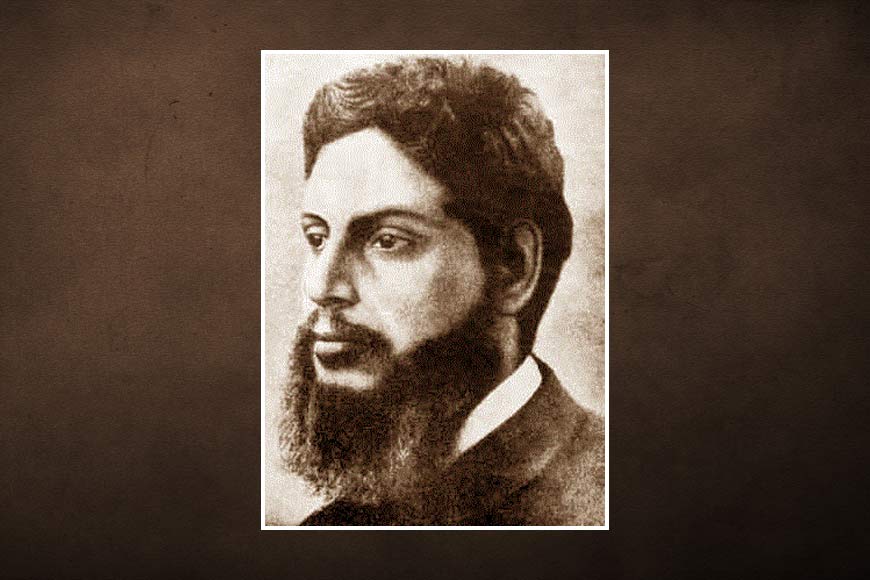

Upendrakishore Raychaudhuri, the boy who refused a zamindari

To begin with, he was not called Upendrakishore. Named Kamada Ranjan Ray at birth, he was the youngest of three sons born to Joytara and Kalinath, and later adopted by his father’s childless cousin, Harikishore Ray. Formally declared as Harikishore’s son in 1868, the five-year-old, born on May 12, 1863, was given the shiny new name of Upendrakishore Raychaudhuri. This was the name that would make him internationally famous as a pioneering printer and publisher, a writer of children’s books, and father and grandfather to two other icons of Bengal - Sukumar and Satyajit Ray.

A shirastedar (serestadar in Bengali, derived from Persian, chief administrative officer of a District & Sessions Court) in the Diwani Adalat, Harikishore was a devout Hindu who had been terrified that he would die without a male heir, and therefore denied entry into heaven since his last rites would not be performed by a son. An otherwise honest, sincere man, he was well-paid enough to acquire a zamindari estate and modify his last name to the more aristocratic-sounding Raychaudhuri. Both the families were based in Masua, Mymensingh (Kishoreganj district in modern day Bangladesh), then the largest district in the Bengal Presidency and one of the largest in India.

Completely devoted to their ‘new’ son, Harikishore and his young third wife Rajlakshmi lavished an excessive amount of love on Upendrakishore, unfortunately creating a pampered brat. As so often happens in life, however, a twist in the tale was imminent. Only two years or so after the adoption, the hitherto childless Harikishore began producing offspring with a vengeance - son Narendrakishore, and daughters Manorama and Surabala. From all accounts, though, Upendrakishore was still treated as his adoptive father’s heir, and his family’s affection for him remained strong as ever.

The bright young boy was more interested in music and art than academics, but that did not concern his father. What Harikishore was truly afraid of was the rapidly growing trend of young Hindu men converting to Brahmoism, and even forbade Upendrakishore from associating with his close friend and distant relative Gagan Chandra Home, who had run away from home to live in a sort of Brahmo youth hostel. The thought of what would happen to his estate should Upendrakishore follow his friend’s example and leave home probably gave Harikishore sleepless nights.

And yet, that is almost exactly what came to pass. Like thousands of other boys from rural Bengal, the 16-year-old Upendrakishore, armed with a scholarship, travelled to Calcutta in 1879 in pursuit of a university education. Initially having enrolled at the elite Presidency College, he switched to the less glamorous Metropolitan Institution (set up for poor students by Ishwarchandra Vidyasagar as a ‘national’ alternative to the very expensive Presidency College). It was from here that he eventually graduated in 1884 in the third division.

Clearly, the rebellious streak had begun to show. For the first time in his life, the 21-year-old was facing financial hardship, most possibly as a result of friction with Harikishore, who wanted his son to earn a coveted and lucrative law degree. The son was absolutely against it, which may have caused a reduction in his allowance, causing the shift from the pricey Presidency to the modest Metropolitan. We must remember here that Harikishore had himself made a fortune as a legal professional, so it was probably natural for him to think that legal training would prepare Upendrakishore for the task of managing the estate.

The other, bigger cause for conflict, however, was Upendrakishore’s growing closeness to the young, radical Brahmos of Calcutta. Shortly before his death in 1883, a desperate Harikishore actually made a new will, leaving only a fourth of his estate to Upendrakishore and the rest to Narendrakishore, clearly hoping that this would bring Upendrakishore back to the family fold.

It soon became equally clear, however, that the implacable Upendrakishore had decided that the life of a rural zamindar in a corner of Mymensingh was not for him. Indeed, even as he studied for his BA degree, he took on the ‘inferior’ job of repairing damaged musical instruments, possibly for Dwarkin’s, a prominent Indian dealer in musical instruments at the time. He also did some music tutoring and planned to write a book on science for children. All this to probably supplement his income, since he obviously felt he could no longer seek financial support from his family.

His various activities could well have contributed to his poor academic record, and when family and friends requested him to return to Masua and take charge of the estate after Harikishore’s death in 1883, he agreed only on the impossible condition that he would run the estate without ever lying or performing a single unethical act. Recognising a refusal when they saw it, his family accepted his decision, and the teenage Narendrakishore was forced to give up his studies and take over the estate.

But a further twist remained. Upendrakishore refused to perform the orthodox Hindu funeral rites for his adoptive father, such as feeding Brahmins and distributing alms. With this, the writing was truly on the wall, and though he had not formally converted yet, his religious sensibilities had already been reshaped by the tenets of Brahmoism, making it impossible for him to support the casteism inherent in the funeral rites. So young Narendrakishore had to step in once more.

By now, Upendrakishore had launched the block-making business that was to become U. Ray & Sons. Again, this decision may well have been prompted by Brahmo tenets, which encouraged the entrepreneurial spirit and private enterprise. Shortly after starting his own business, Upendrakishore formalised his secession from Harikishore’s orthodox Hindu world by converting to Brahmoism in 1884.

Source: The Rays Before Satyajit: Creativity and Modernity in Colonial India by Chandak Sengoopta