Think you know all about our tricolour? Think again!

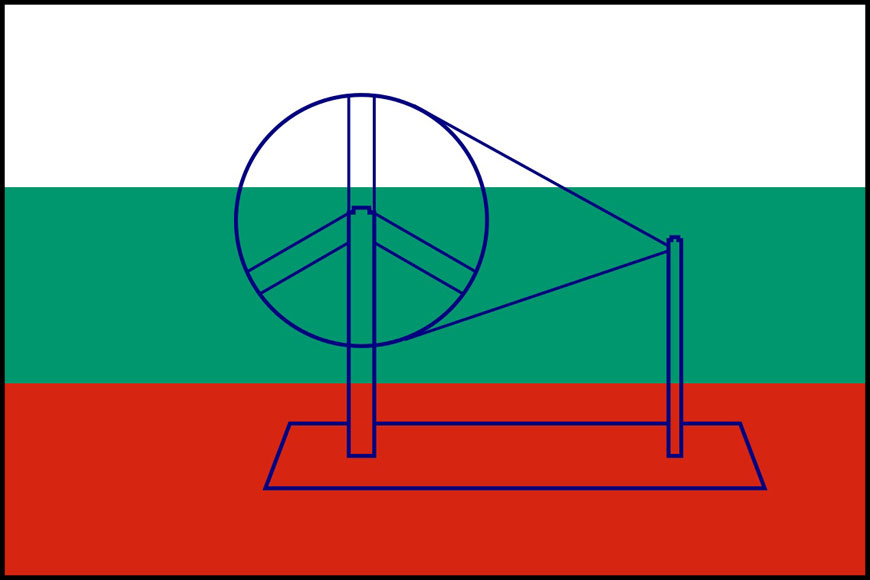

The flag designed by Mahatma Gandhi in 1921

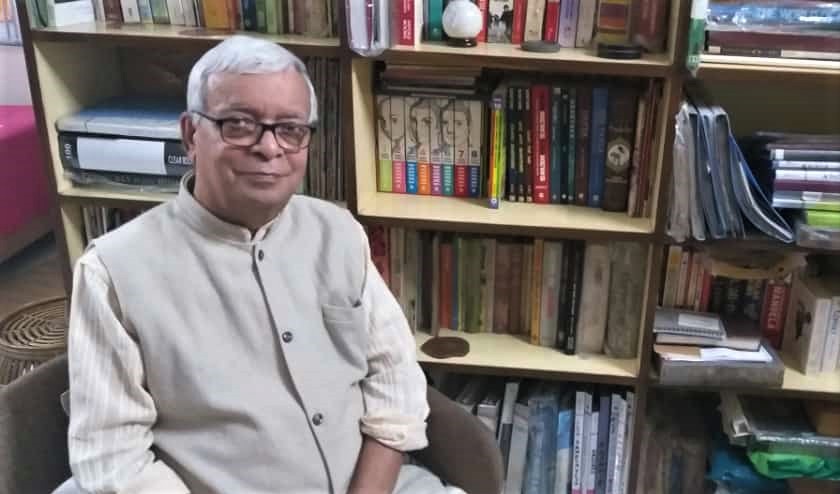

‘Vexillology’ - try pronouncing that quickly. This tongue twister of a word has a fairly simple meaning, however, it means the scientific study of flags. And India’s 74th Republic Day provides the perfect opportunity to talk about India’s national flag with Kolkata’s best-known vexillologist Sekhar Chakrabarti, a sprightly 77-year-old retired engineer, whose passion for stamps progressed to a parallel passion for flags when he was 15, thanks to his introduction to ‘thematic stamp collecting’ at Kolkata’s Indo-American Society. As it happened, the teenager already had a fair number of flag-based stamps in his collection, and an abiding interest in flags was the logical next step.

Today, he has a few myths to bust about the origin of the Indian tricolour, and talks about the various ups and downs during its evolution. In 2012, Mr Chakrabarti published a highly instructive volume titled ‘The Indian National Flag Unfurled through Philately’, encompassing his twin passions, and the book is a reminder of why we should not necessarily believe all that we are told.

Vexillologist Sekhar Chakrabarti

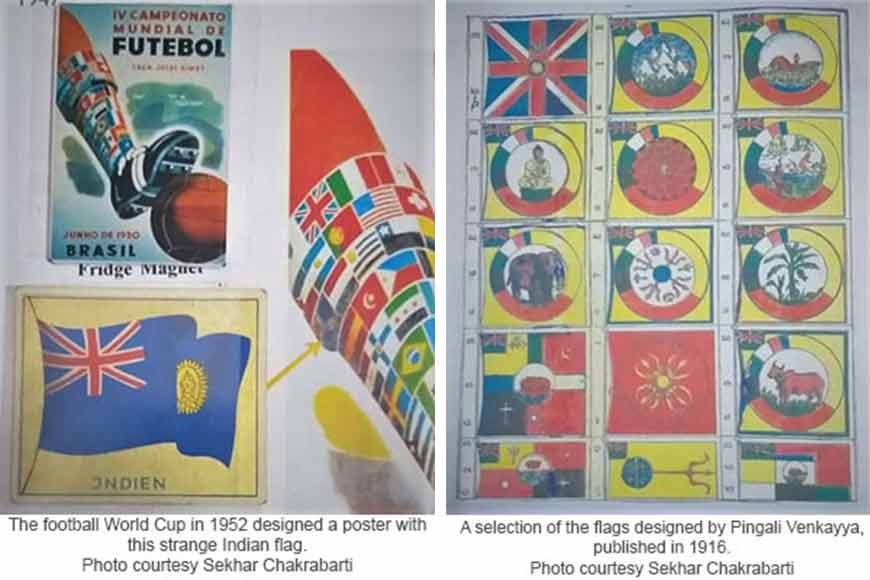

The most widely circulated theory about the origin of our flag is that its design is based on an idea put forth by Pingali Venkayya, a freedom fighter born near Machilipatnam, in what is now Andhra Pradesh. This, despite the fact that the first serious attempt to create a pan-Indian flag was made by Sister Nivedita in Calcutta in 1904. Considering Venkayya’s contribution, how was it that he was allowed to die in poverty in 1963, largely forgotten by the country and his own party, the Congress? Yes, a postage stamp was issued in his honour in 2009, but a 2011 proposal to posthumously declare him a ‘Bharat Ratna’ was given a quiet burial.

Why such indifference? One reason, as Mr Chakrabarti says, is that no matter what we have been told, Venkayya was not the sole originator of our tricolour, though he was one of the pioneers. In fact, his early attempts to design a national flag were treated somewhat coldly by none other than Mahatma Gandhi. In an article titled ‘The National Flag’ published in Young India in 1921, he wrote, “While I have always admired the persistent zeal in which Mr Venkayya has prosecuted the cause of a national flag at every session of the Congress for the past four years, he has never (been) able to enthuse me; and in his designs I saw nothing to stir the nation to its depths…”

These designs, compiled in a booklet, almost uniformly featured the British Union Jack in one corner, which was ironic considering the purpose of the flag. Also ironic was the fact that since the entity called ‘India’ was essentially a British creation, the only flags seen in the subcontinent prior to the 20th century were the ones belonging to individual princely states and kingdoms, since ancient times.

In Mr Chakrabarti’s opinion, when it comes to India’s national flag, “they have mixed up the designer and the maker”. According to his book, before the Bezwada (later Vijayawada) session of the Congress in April 1921, Gandhiji sent Venkayya back to the drawing board with instructions, and the latter came up with a bicolour design of vertical red and green panels, symbolising Hinduism and Islam, with a charkha in the foreground. The idea of the charkha, as records show, came not from Gandhiji, but from eminent educationist Lala Hansraj, and Venkayya simply followed this brief.

While a detailed description of the birth of the tricolour is not the purpose of this article, it needs to be mentioned that after some consideration, Gandhiji added a white band to the flag, to symbolise all other religions. “The connotations were communal,” says Mr Chakrabarti, “and this created problems later. Parsis wanted representation, Jains wanted representation, but they were not very vocal. In contrast, the Sikhs issued an outright threat - if our colour is not included, we will pull out of the Non-Cooperation Movement.”

Jawaharlal Nehru wanted to pacify the various groups, but there was no way every religion could find individual representation. Interestingly, says Mr Chakrabarti, the suggestion to include saffron (bhagwa or gerua), and to change the charkha to a mace (gada), came from Kolkata’s Sanskrit College. “Things were becoming complicated, and instead of unifying, the flag was causing divisions,” he laughs. “Nonetheless, as a Swadeshi flag, this tricolour became popular among certain sections of people, and they began raising it on several occasions.”

However, unanimous acceptance was still a far cry, and in 1931, the Congress decided that a Flag Committee was needed to finalise a flag acceptable to all. By now, Gandhiji had seen the need to discard religious connotations and adopt a more philosophical approach. The committee, headed by Dr Pattabhi Sitaramayya, sent out a questionnaire to several eminent Indians, soliciting suggestions for such an ensign.

Writing to Sitaramayya in April 1931, Nehru himself was unambiguous: “We should make it perfectly clear that our flag is not based on communal considerations. Perhaps some change is necessary. This change, however, should not interfere too much with the present flag.” And a little later, he added, “The present flag is, I believe, identical with the Bulgarian flag. This is undesirable…”

In an article titled ‘The National Flag’ published in Modern Review in June 1931, Professor Suniti Kumar Chatterji also cautioned that any explanation of the colours of the national flag as symbolic of Hindus, Musalmans, Christians and any other community should be regarded as “pernicious and anti-national”. He also pointed out that red, white, and green already featured in the flags of at least four countries: Persia, Italy, Bulgaria, and Mexico. To avoid confusion, Prof. Chatterji suggested vertical bands of red, green, and ochre or saffron, with the three- or four-spoked wheel (or four- or eight-petalled white lotus) in the central field.

In the end, the Flag Committee’s final recommendation - an entirely saffron flag with a charkha in the top left corner - was summarily rejected by the Congress Working Committee in 1931, and a new design for a Purna Swaraj flag was put forth. It may be noted that Pingali Venkayya, the supposed ‘designer’ of the original flag, was now well out of the picture.

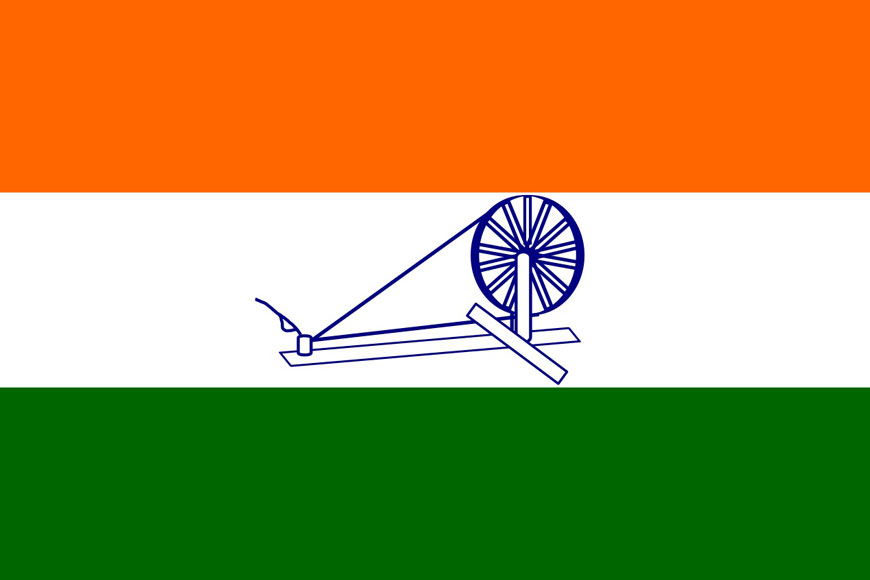

The Purna Swaraj flag adopted in 1931

“It is established that Pingali Venkayya was not the designer of this flag, but the myth still persists that it was he who designed our flag,” says Mr Chakrabarti. The new flag was to substitute saffron for red, with white in the middle and green underneath, and the charkha in navy blue in the foreground.

While the thorny issue of religious representation had been sorted out, however, the charkha was not universally popular either. No less a personage than Rabindranath Tagore, and later Suniti Chatterji, objected to it on several grounds. However, the first to protest was Andhra Pradesh, according to eminent research scholar D.V. Sivarao.

In a broadcast from All India Radio in October 1953, Sivarao claimed that the idea of including a chakra instead of the charkha was first conceived in May 1925 by ‘Andhra Ratna’ D. Gopalakrishnayya, who called the charkha “Gandhi’s toy” and wrote, “A simple Charka may exhibit the sorrow of the stomach merely. It is puerile to think that it suffices to indicate the Nation’s condition and concern. If Mahatma Gandhi also thinks so, well, I shut up!”

Several years later, yet another flag committee was to adopt the Purna Swaraj flag as India’s national flag on July 14, 1947, simply substituting the charkha with Emperor Ashoka’s ‘Dharma Chakra’, not least because the chakra was easier to print than the more complicated charkha. A sample made by Mrs Badr-ud-din Tyabji was approved on July 17, 1947, and it was decided that Nehru would place the sample before the Constituent Assembly on July 22.

Gandhiji was unhappy with the final look. As late as August 6, 1947, speaking in Lahore and quoted in the Statesman, he said, “I must say that if the flag of the Indian Union will not embody the emblem of the Charkha, I will refuse to salute that flag. You know the national flag of India was first thought of by me, and I cannot conceive of India’s national flag without the emblem of the Charkha. We have, however, been told by Pandit Nehru and others that the sign of the wheel or Chakra in the national flag symbolises the Charkha also…”

Whether Gandhiji agreed or not, however, the flag was now decided. However, given the impossible deadline which Lord Mountbatten had set for India’s Independence, and the rush to hand over power by August 15, 1947, the world seemed unaware of India’s sovereign status, and its flag, even a good five years later.

Few Indians will be aware that the only football World Cup in which India had a chance to participate was the one held in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in 1952. That they finally didn’t make it to the tournament, primarily owing to financial reasons, is another matter. What is truly astounding is the World Cup poster, showing India’s flag as a strange blue piece of cloth, with the Union Jack in one corner (pictured above)! How on earth the Brazilians got hold of it remains a fascinating mystery. In Nehru’s immortal words, India had awoken “to life and freedom” in August 1947. Clearly, the world needed a while to catch up.