The Tagorean vision which India forgot

The Civil Disobedience Movement was a non-violent protest against British rule that lasted from 1930-34, led by Mahatma Gandhi and beginning with the Dandi March.

This is widely recorded history. But decades before civil obedience became an official movement, a young man was reading a paper at a private meeting in Kolkata in 1884. The 23-year-old was called Rabindranath Tagore, whose death anniversary we observed on August 6.

In a telling paragraph, he wrote: “We may appear to be gaining as Government granted us one privilege after another. But who cared to enquire after the injury that unknown to us occurred? Do we not as often cry out - ‘victory to the profession of begging’? Carry on agitation by all means but direct it to your own people; …educate yourselves, educate your people.”

Astonishing as this sentiment may seem for a man in his early 20s, the years to come further solidified this spirit of non-cooperation and civil disobedience. Next stop, the path-breaking essay titled ‘Swadeshi Samaj’, based on which, in 1904, he drew up a draft which envisaged a socio-political reconstruction of Indian society, based on a complete dissociation from the British administration and its myriad of institutions.

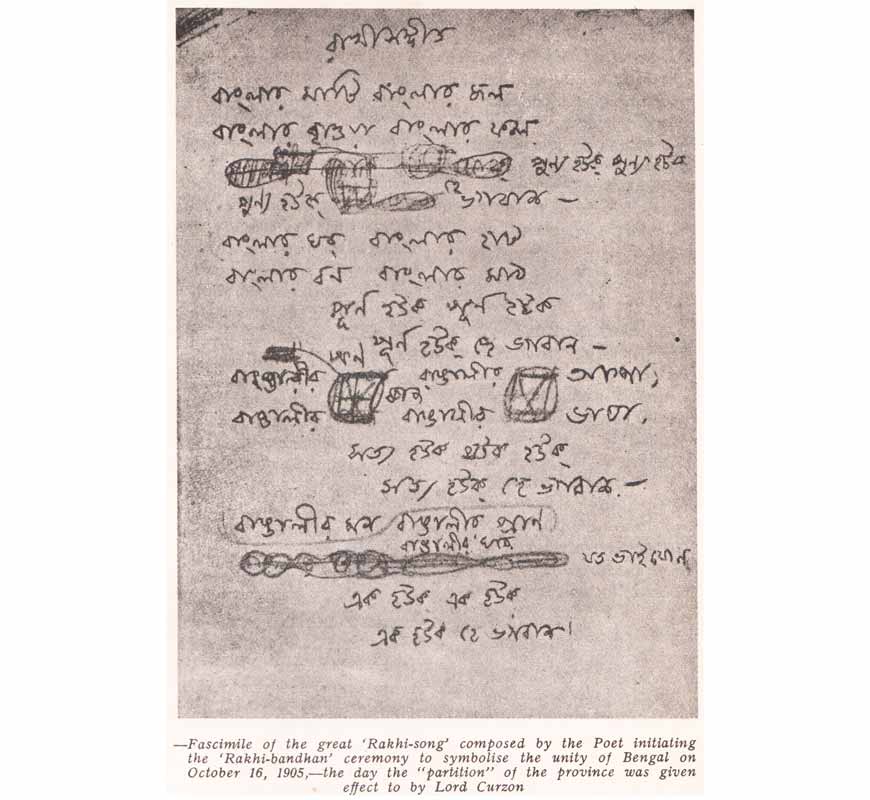

Written in Bengali, the draft isn’t extensive. But it is comprehensive. Meant for private circulation only, on the ‘to do’ list were such strictures as discarding all foreign-made clothes and items of personal use, not writing letters in English unless absolutely required to do so by one’s profession, not inviting English guests to gatherings, or if so, then serving them Bengali food only, to be eaten in the Bengali manner!

On a more serious note, the draft also proposes an entirely indigenous system of education run by Indians, patronising Indian businesses only, and refusing to approach the government to deal with any social issues arising within ‘native society’.

As historian Bipan Chandra wrote in Indian Nationalism: Its Principles and Personalities, Tagore was the first to preach the duty of discarding all voluntary associations with official activities and organising our social, economic and educational life independent of official help and control.

In The Golden Book of Tagore, B.C. Chatterjee recounts the rousing rendition of ‘Amar Sonar Bangla’ by the poet at Town Hall, in which the entire gathering joined in. This was the basis of Tagore’s version of nationalism, a term with which he had long-standing problems. In fact, as he saw his idea of swadeshi being incorporated into the larger ideal of violent nationalism, he gradually began to withdraw from active participation in the movement.

So by the time the non-cooperation and civil disobedience movements became official, one of their principal architects was no longer actively associated with them, at least not in the public domain. Today, the country at large remembers him principally as the creator of our national anthem. While that is a glittering crown in itself, it would be even more lustrous were everyone to recall the debt to his vision of an independent India, long before ‘Jana Gana Mana’ became a reality.

Source: Rabindranath and the Political Awakening in India by Suresh Chandra Deb, published in the Calcutta Municipal Corporation Gazette’s Tagore Memorial Special Supplement, September 13, 1941