The Swiss woman who wrote the first Bengali novel

Asked about the first published novel in Bengali, most of us would probably say ‘Alaler Gharer Dulal’ (1857-58), written by Peary Chand Mitra under the pseudonym Tekchand Thakur. And we would be wrong. While a pioneering novel in many ways, this wasn’t the first published novel in Bengali. That honour goes to a book that all but a handful of scholars have forgotten, written, of all people, by a Swiss woman.

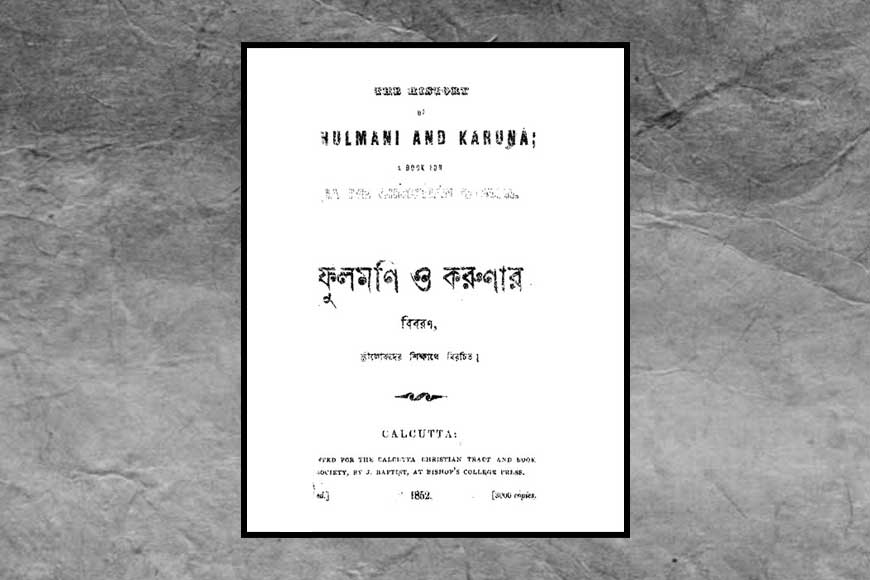

The novel in question is ‘Phulmani o Karunar Biboron’, published in Bengali in 1852 and rapidly translated into several Indian languages thereafter. Forgotten for about a century, the novel was rediscovered in the 1950s by Chittaranjan Bandyopadhyay, then employed at the National Library. Going through old Bengali books for a particular project, he stumbled upon the 300-page book, its pages crumbling, but professionally printed. He didn’t find any author’s name anywhere, but going through the book, realised it must have been written by a woman. Finally, he consulted an old catalogue to find out that the author’s name was Hana Catherine Mullens. Realising the value of the book, Bandyopadhyay had the book republished in 1959.

Born Hana Catherine Lacroix in Calcutta, she was the daughter of Alphonse François Lacroix, a Swiss Protestant missionary who went to Chinsurah in 1821, and Hannah Herklots, who was from a Dutch colonial family. Thanks to her interactions with household staff since a young age, she developed an astonishing command over spoken Bengali at a very early age. So much so that when she was only 12, she began teaching Bengali in a newly established school. The family travelled back to Europe when she was 15, and Hana trained to be a teacher in London before returning to Calcutta.

In 1845 she married Joseph Mullens, a fellow missionary, who had travelled out to India on the same ship as Hana’s father. The couple continued their work in Calcutta for several more years. Because of her fluency in Bengali, Hana became head of a boarding school for girls, and taught Bible classes to women. Apart from Phulmani o Karunar Biboron, which bore the tagline that it had been written ‘for the benefit of women’, Hana’s lasting legacy will remain the zenana missions (zenana were the secluded living quarters of girls and women, similar to purdah), where Hana began an outreach programme to educate women. Having persuaded the widow of a Hindu doctor to accommodate zenana teaching in her home, she negotiated other similar arrangements. By the time of her death in 1861, she was overseeing four zenana missions and visiting another eleven missions every day.

Thus, over two decades before Swarnakumari Devi became the first Bengali woman to write a novel (Deepnirban in 1876), Hana Catherine Mullens had broken new ground and gone where no one had gone before. Happily, her book is once again available for readers, and irrespective of literary merit, deserves to be read for its historic value alone.