The story behind the birth of a song that is an emotion for Bengalis worldwide

Amar bhai er rokte rangano ekushe February/ Ami ki bhulite pari’ (How can I forget the blood soaked 21st February/ soaked in the blood of my brother)

These lines from a song have transcended the mere boundaries of the written word or the musical note. They have become representative of an entire movement, a movement that, 50 years later, prompted the United Nations General Assembly to adopt February 21 as International Mother Language Day in 2002.

‘Ekusher Gaan’, as it is now known to Bengalis the world over, is therefore an emotion. It lies at the heart of the Bhasha Andolan or Language Movement, which catalysed the assertion of Bengali national identity in East Bengal, later East Pakistan, and became a forerunner to Bengali nationalist movements, including the 6-Point Movement and subsequently the Bangladesh Liberation War and the Bengali Language Implementation Act, 1987.

It is the song that reminds the world why Bengali is an official language at the UNGA, and how a battle against the imposition of Urdu on a Bengali-speaking populace eventually resulted in the birth of a country. Which ought not to come as a surprise, considering that Bengalis are the third-largest ethnic group in the world, after the Han Chinese and Arabs. Thus, they are the largest ethnic group within the Indo-Europeans and the largest ethnic group in South Asia.

Also read : The language movement that led to freedom

But how exactly did the song come to be created? The answer lies in a horrifying tragedy that unfolded on February 21, 1952, the roots of which go all the way back to 1937, when delegates from Bengal rejected the idea of making Urdu the lingua franca of Muslim India at the Lucknow session of the Muslim League.

Post-Partition, a series of face-offs began between East Pakistanis who pushed for Bengali as the official language of the region and the high-handed government of West Pakistan, most of whose representatives were Urdu speaking Punjabis. Students from the University of Dhaka and other colleges called for a general strike on March 11, 1948 to protest the non-usage of Bengali for official purposes, including coins, stamps and recruitment tests for the navy. The strikers restated the demand that Bengali be declared an official language of the Dominion of Pakistan.

On January 31, 1952, the Sorbo Dolio Kendriyo Rashtrabhasha Kormi Parishad (All-Party Central Language Action Committee) was formed at a meeting at the Bar Library Hall of Dhaka University, chaired by Maulana Bhashani. The committee declared an all out protest on February 21, including strikes and rallies. In retaliation, the government imposed Section 144 in Dhaka, banning all gatherings.

On the morning of February 21, students began gathering on the university premises in defiance of Section 144 as armed police surrounded the campus. When a few students gathered at the university gate attempted to break the police line, the police fired tear gas shells in warning. As many students attempted to leave and some entered Dhaka Medical College, the police arrested several for violating Section 144.

On the morning of February 21, students began gathering on the university premises in defiance of Section 144 as armed police surrounded the campus. When a few students gathered at the university gate attempted to break the police line, the police fired tear gas shells in warning. As many students attempted to leave and some entered Dhaka Medical College, the police arrested several for violating Section 144.

Abdul Gaffar Choudhury, a final-year student of medicine, arrived at the medical college when he heard of the police firing. One of the first sights that met his eye was the body of Rafiquddin lying in the outdoor ward, half of his skull blown away by bullets.

Overwhelmed by grief and anger, Choudhury participated in a huge funeral procession on February 22, following which a large and spontaneous public rally was taken out. Inevitably, the police cracked down on the rally, and Choudhury was among those beaten so savagely that he lost consciousness. Friends removed him to a safe house in Gendaria, where he began writing the 30-line poem despite his grievous injuries, a poem that was later to become the anthemic song.

Overwhelmed by grief and anger, Choudhury participated in a huge funeral procession on February 22, following which a large and spontaneous public rally was taken out. Inevitably, the police cracked down on the rally, and Choudhury was among those beaten so savagely that he lost consciousness. Friends removed him to a safe house in Gendaria, where he began writing the 30-line poem despite his grievous injuries, a poem that was later to become the anthemic song.

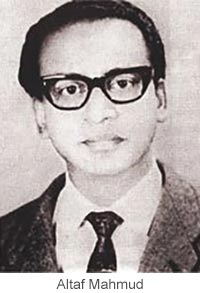

Abdul Latif was the first to set the poem to music, which Atikul Islam first sang. The students of Dhaka College also sang the song as they attempted to build a Shaheed Minar or martyrs’ memorial on their college premises, resulting in their expulsion from college. Altaf Mahmud, a renowned composer and martyr of the Bangladesh Liberation War, later recomposed the song using Latif’s version, and this second version became the more widely accepted rendition.

First performed for the wider public as part of a morning rally in 1954, the song has been translated into 12 languages according to Bangladeshi media accounts, and is widely performed every year on February 21 as people walk barefoot to the Shaheed Minar in Dhaka as a gesture of mourning for the young people who gave their lives for their mother tongue.