The Rise of the Nation

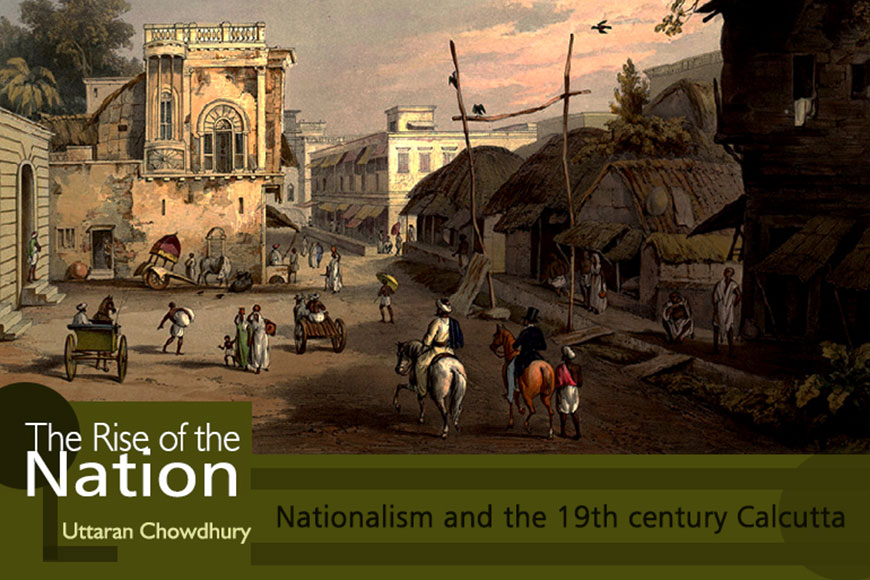

What is a nation? A satisfactory answer to this question was not present in early 19th century Calcutta. Back then, after the deadly cholera outbreak of 1817, the lottery committee was clearing forests and filling up ponds to set up new residential areas, and privately-owned elephants traversing public roads started to become a rare sight. However, the opulence and luxury of the jewels on the crown, that is, the privileged few of the city, had not diminished one bit. Their palatial mansions regularly hosted myriad celebrations of Holi, Durga Puja, and other festivities with inordinate lavishness. Furthermore, there were also no stones left unturned while arranging for expensive entertainments like amateur wrestling matches and kite flying tournaments. In the midst of such pomp and show, however, Calcutta was also home to the “black town” residents – the daily labourers, the beggars, the prostitutes, the sick and the anti-socials who occupied the seediest, most impoverished corners of the city. In the richer strata of the society, masters came to teach the little heirs of the family French and the letters. However, the concept of nation was still not a part of their curriculum. On the contrary, there was an unsolicited enthusiasm with regard to hobnobbing with one’s European guests at the countless dinner parties and dances housed at the palaces of Shovabazar, Jorasanko, Shimulia and Hatkhola. That was the era when the English language was making its impact felt around Britain and her colonies. And soon, the official language of the court was also made English in lieu of French.

This notable development inevitably caused the Bengali intelligentsia of the city to be spurred to action. And within a few days, in 1817, the Hindu College was established by David Hare, Dewan Baidyanath Banerjee, the Supreme Court Chief Justice Edward Hyde East and the Bengali “managers” of yore. Though the institution was targeted towards the Hindu populace, it began teaching English literature and the sciences instead of Hindu philosophy. With an eminent roster of European professors, the college consisted of a student body of affluent heirs of the zamindar families as well as a few poor yet exceptionally brilliant “free” scholars. For the first time in the history of Calcutta, the boundaries of the prevalent caste system became blurred and individuals belonging to different familial and socio-economic backgrounds sat and studied in the same classroom, partaking of the cool air provided by the same manually operated fan.

From 1826 onwards, more and more students began to attend the Hindu College. The reason was the presence of a certain young professor called Henry Derozio who had joined the institution to teach History and English literature from the month of May that year. He was himself a scholar of Scottish Enlightenment as well as the protégé of David Drummond. And soon, he came to be renowned as a much-coveted instructor of the philosophies including those of Locke, Berkeley, Bacon, Hume and many others.

With this momentous development, years of religious prejudices, superstitions and perceived differences were transcended to give birth to a few young, liberal minds. And this boundless canvas of nascent, egalitarian attitudes, in a way, became the microcosm of a budding nation. The newly emerging free-thinkers of the young generation were broadening their horizons beyond their geographical limitations to experience a continual destruction of their personal Bastilles in favour of celebrating the three ideals of the French Revolution – Liberty, Equality and Fraternity.

Indeed, the winds of change had been signalled. Till then, along with many different native merchants, even eminent personalities like Raja Rammohan Roy and Dwarkanath Tagore had believed in the promised social and economic advantages of the British Raj. At this crucial juncture, however, Derozio broke ground by depicting the nation as a goddess who has to be cherished and protected in his poem “To India – My Native Land”. Again, Parthenon published different articles authored by Derozio’s students that questioned the legitimacy of the presence of English colonists in India. On the other hand, at the Indian Gazette magazine, Kashiprasad Ghosh – arguably the first native poet writing in the English language – lamented:

Land of the Gods and lofty name;

Land of the fair and beauty’s spell;

Land of the bards of mighty fame;

My native land! For ever fare well!

This watershed moment in history also coincided with Titumir’s fiery rebellion and the refusal of the Indian Army to assist the British in the Anglo-Burmese War. Simultneously, the palanquin-bearers of Calcutta also pioneered the much-replicated practice of going on strike. And on top of the newly-built Ochterlony Monument (later renamed as the Shaheed Minar), one fine day, someone raised the French flag to symbolise the triumphant rise of independent thought and expression.

Indeed, this was how Calcutta learned her first lessons towards achieving freedom for herself and the nation. And in the process, the city also went on to become the launch pad of nationalism as well as an enduring icon of hope and inspiration for the rest of the country.

Translated by Mayurakshi Sen