The man, the actor, and my Soumitra 'kaku'

When I first met Soumitra Chattopadhayay, he was a friend’s father. This was the early 1980s, and a poet friend of mine, Bitan Bhowmik, introduced me to another poet friend of his called Sougata, and we landed up at Sougata’s place to find that he had a father whose name was Soumitra Chattopadhyay.

Growing up, we were used to mothers who were devoted to Uttam Kumar. On the other hand, Soumitra Chattopadhyay seemed to appeal more to our elder siblings, the next generation, as it were. Poetry, literature, art, were also important components of the growing up experience, and the literary magazine ‘Ekkhon’ was a cultural staple in the home in which I grew up. All of which had created an aura around ‘Soumitra’ the star, the actor, the cultural icon.

In my mind, these various forms of address became aligned with the characters he played. When I thought of him as ‘Soumitra babu’, it was probably in the context of some extraordinary bit of work that he had done, which had so stunned me that it absolutely precluded the possibility of calling him something as familiar as ‘kaku’.

It was against this backdrop that Sougata invited us to his home, we climbed up the stairs of the Lake Temple Road house, and were sitting chatting in his room when his father entered, with a banal question which went something like, “Bubu, where have you kept that book of mine?” Like any other father, in short. We stood up, as a standard gesture of respect to an elder, but not entirely so. While the fathers of other friends automatically became ‘Mesomoshai’ (an uncle, but with an unmistakable elderly tag attached), we simply couldn’t see this particular father in that light. What did one call a silver-screen leading man? In the end, after much thought, we settled upon a compromise solution, ‘Kaku’ (a decidedly more youthful uncle). I have looked up to quite a few people as gurus, in life. My father was one of them. Soumitra Chattopadhyay was to become another, but more on that later.

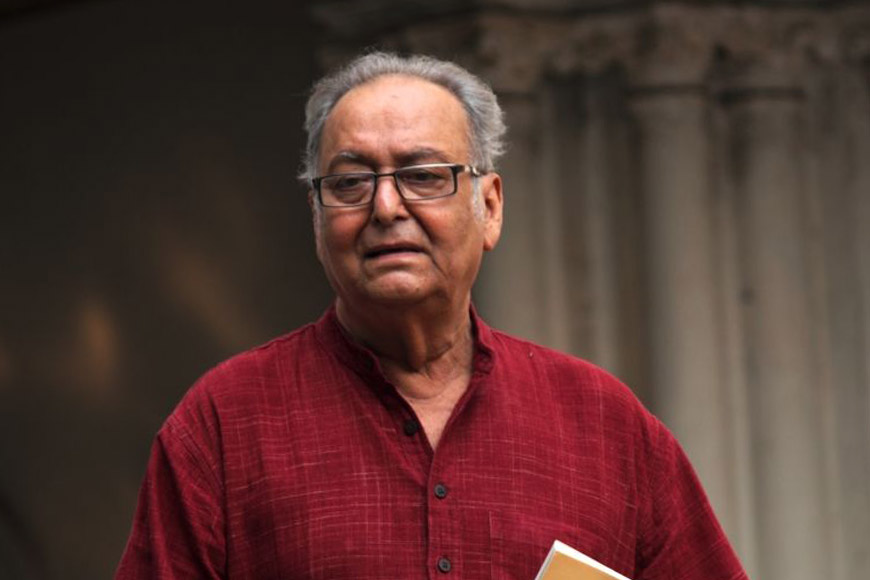

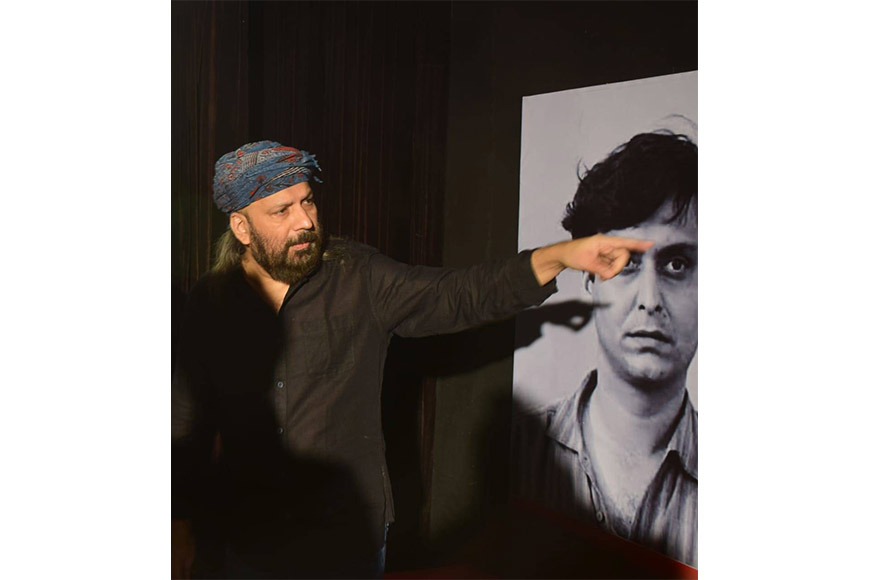

Debojyoti Mishra with Soumitra Chattopadhayay

Debojyoti Mishra with Soumitra Chattopadhayay

Sougata was a highly accomplished violinist, too. And when it came to Western classical violin pieces, it was at his house that I first heard Beethoven’s ‘Spring Sonata’, for instance, or his ‘Choral Symphony’. We had launched a magazine called ‘Setu’, to which Soumitra kaku would occasionally contribute poems, and we tried very hard to be nonchalant and airily dismissive about it - “Yeah yeah, Soumitra Chatterjee, we know.” In his turn, he was tremendously affectionate to all friends of his children, particularly those who were culturally inclined.

The music for ‘Lear’ happened in several stages, and evolved and changed as I went along. At one of the rehearsals, Soumitra babu suddenly called out from the stage, peering into the blinding stage lights, “Is Debojyoti here?

As the years went by and we all went our separate ways, the first time I met Kaku in a professional capacity was during the making of ‘Patalghar’ (2003), in which he was playing Aghor Sen. “Ah, so you’re doing the music are you?” was the first thing he said. And I realised that to all and sundry, he was ‘Soumitrada’, even to people younger than me. How could I call him ‘kaku’ in public? Typically, he was unbothered by this when I sheepishly raised the question. “Call me whatever you’re comfortable with,” he said. Gradually, without my realising it, he transformed from ‘Soumitra kaku’ to ‘Soumitrada’, even occasionally ‘Soumitra babu’.

In my mind, these various forms of address became aligned with the characters he played. When I thought of him as ‘Soumitra babu’, it was probably in the context of some extraordinary bit of work that he had done, which had so stunned me that it absolutely precluded the possibility of calling him something as familiar as ‘kaku’. I simply had to view him from a distance. He was then as necessarily remote as a Satyajit Ray, or a Salil Chowdhury, resident of a far away galaxy.

In ‘Patalghar’, his character had to sing a song, and he told me, “Look, I’ll do the opening notes, but not the whole song.” So we called in Srikanta Acharya, and discussed Soumitra babu’s speaking voice, creating the proper tone.

In ‘Patalghar’, his character had to sing a song, and he told me, “Look, I’ll do the opening notes, but not the whole song.” So we called in Srikanta Acharya, and discussed Soumitra babu’s speaking voice, creating the proper tone.

For ‘Mayurakshi’ (2017), director Atanu Ghosh told me that Soumitra babu’s character would spontaneously burst into song in a coffee shop, where his son had taken him. “Everyone needs some background music in their lives,” he was to say, before breaking into song. For the dummy recording, I sang the song, without even thinking about how he was going to sing the same song at the age of 83.

I kept running into him socially, and remember discussing the music of Rituparno Ghosh’s ‘Asukh’ on one occasion. There were numerous other casual meetings, too, but the next time we worked together was for Suman Mukhopadhyay’s play ‘Raja Lear’ (2011). At the press conference at Minerva theatre for ‘Lear’, after I had said my bit, Soumitra Chattopadhay unexpectedly launched into a detailed discussion about the music, the first time he had done so in all these years. “I believe the play is also worth watching purely for Debojyoti’s music,” he declared. I was peculiarly affected by this, a feeling far removed from my familiarity with him, his home, and his non-star persona.

The music for ‘Lear’ happened in several stages, and evolved and changed as I went along. At one of the rehearsals, Soumitra babu suddenly called out from the stage, peering into the blinding stage lights, “Is Debojyoti here? Is that his voice I can hear?” I responded, and he asked, “Have you made changes to the music here? Can you show me where?” And then he said, “Don’t change this again, because I’ll have trouble marking my position.” All I saw then was what a tremendous professional he was, detecting even minute changes in the music because they impacted his position on the stage at that point.

Yet another area where we met as professionals was art, since we were both painters. I had held a few exhibitions by then, and remember him saying, “We are both professionals now, and both of us are crazy painters. It would be great if people took our efforts seriously.” These personal moments will stay with me forever.

For ‘Mayurakshi’ (2017), director Atanu Ghosh told me that Soumitra babu’s character would spontaneously burst into song in a coffee shop, where his son had taken him. “Everyone needs some background music in their lives,” he was to say, before breaking into song. For the dummy recording, I sang the song, without even thinking about how he was going to sing the same song at the age of 83. All I was concerned about was what kind of song this complicated character was going to sing, and the song was accordingly difficult, full of emotional highs and lows, represented musically.

Very few people knew him as a singer, but I did. Many decades ago, an amateur group of which I was a part was rehearsing for a play, and he entered singing ‘Pothe ebar namo sathi’, and asked us, “Don’t you sing Salil Chowdhury’s songs?”

As the dubbing began, Soumitra babu heard the song and said he couldn’t sing it. Atanu was in a fix. And he was so set on Soumitra babu himself singing it that he was prepared to dump the scene if required, because he couldn’t think of a single playback singer whose voice would match. But that would irreparably damage the film. And that was it. As soon as he heard the words “damage the film” Soumitra babu was a changed man. Even so, when he came to the studio, he was clearly still looking for an escape route. I realised that, but kept up my gentle insistence. And when he finally stood in front of the microphone, all it took him was 15 minutes. If you play that sequence again, you will see how flawless his performance was.

Very few people knew him as a singer, but I did. Many decades ago, an amateur group of which I was a part was rehearsing for a play, and he entered singing ‘Pothe ebar namo sathi’, and asked us, “Don’t you sing Salil Chowdhury’s songs?” In fact, my very first recording as a musician was a play he was acting in, when I played ‘O amar desher maati’ on the violin. I was only 18 or so then. And it was because Soumitra babu introduced me to Satyajit Ray that I played for his films, using a violin belonging to Upendrakishore Roychoudhury which Satyajit Ray had gifted to Sougata. I still didn’t own a good enough violin, so I borrowed Sougata’s instrument.

Back to the present, and ‘Borunbabur Bandhu’ (2020). At an unrelated press event, where we were both present, he suddenly summoned me. When I went up to him, he said, “I think the film worked out well, don’t you? I did okay, too, what do you think?” Imagine how inspiring it is for all of us, that an actor at this stage of his career could still be wondering about how his latest film was doing, and his own work in it.

The other thing I will always remember about him is how, all through his life, he remained conscious of his social responsibility as an artist, his unshakeable support for various causes, through his performances, his poetry, or simply his presence, even when he was ill. The sequence in ‘Shakha Prosakha’ where his character has a meltdown, perhaps most accurately captures his own experience as a misfit in society, somebody who listens to Brahms and Bach, who nurtures the kind of values which make it so difficult to survive in the world we have created today.

(As told to Yajnaseni Chakraborty)