"মা আসছেন": The Making of a Durga Puja Pavilion in Kolkata & the Artist Behind It – GetBengal Story

Theme: "Sorbojoner Durgapujo", Purbachal Shakti Sangha, Kolkata

In the city of Kolkata, Durga Puja has always been more than just the worship of the goddess Durga and the metaphoric celebration of good over evil that she represents. Right from the 18th century, there was an element of spectacle in it, which has continued unabated. Every autumn, the city transforms itself into a huge public Art Festival, with the hundreds of “pandals” (pavilions) built all across it to house the goddess and her children becoming veritable Exhibitions, with interactive installation art for all to enjoy. For many decades now, there have been competitions for the best pavilion; the Asian Paints ‘Sharad Samman’, instituted in 1985, being the oldest and most prestigious among them. Also notable, from the turn of the last century, is the increasing number of professional artists who have joined traditional clay-idol makers in creating the idols and designing the pavilions, bringing in a radical shift in the way they are conceptualized and the art consumed by the public at large.

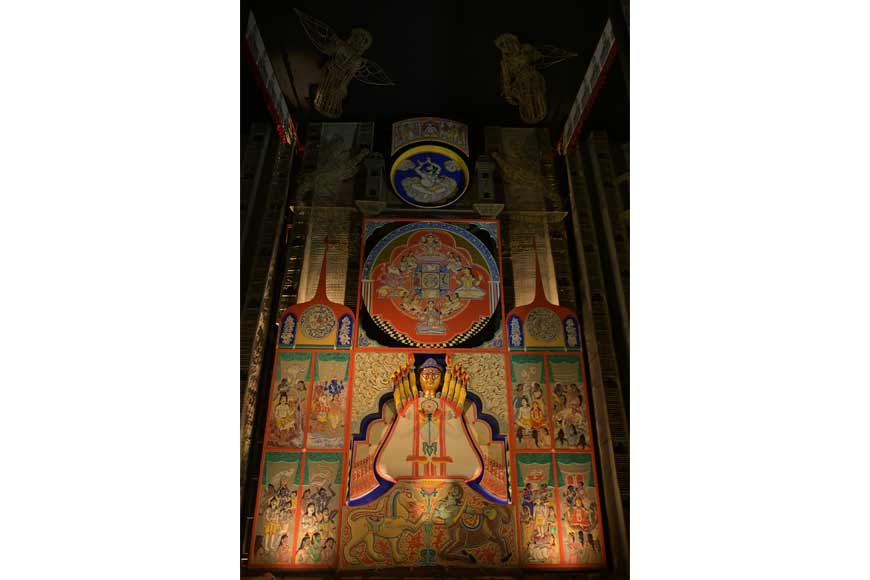

Purbachal Shakti Sangha, 2023

One such artist to make his mark in the pandal-circuit is renowned ceramic arts practitioner, Partha Dasgupta. He has been doing this for two decades – and winning awards, relentlessly! Last year, he mesmerized visitors of the Thakurpukur State Bank Park pavilion in South Kolkata by his replication of the Gurusaday Museum (a rich repository of folk art) and won the Sharad Samman for ‘Shera Pujo’. This year, his effort has been to locate practices – social and artistic, rural and urban – that, over time, went into making the goddess Durga popular and eventually, the cultural brand of Bengal. He identified two such primary examples in the ‘pat’ goddess that is painted and worshipped in the households of Hatserandi village in the Birbhum district of West Bengal, and the 19th century woodcut prints of colonial Calcutta; and has tried to bridge these two in the pavilion of Purbachal Shakti Sangha, under KMC Ward 106.

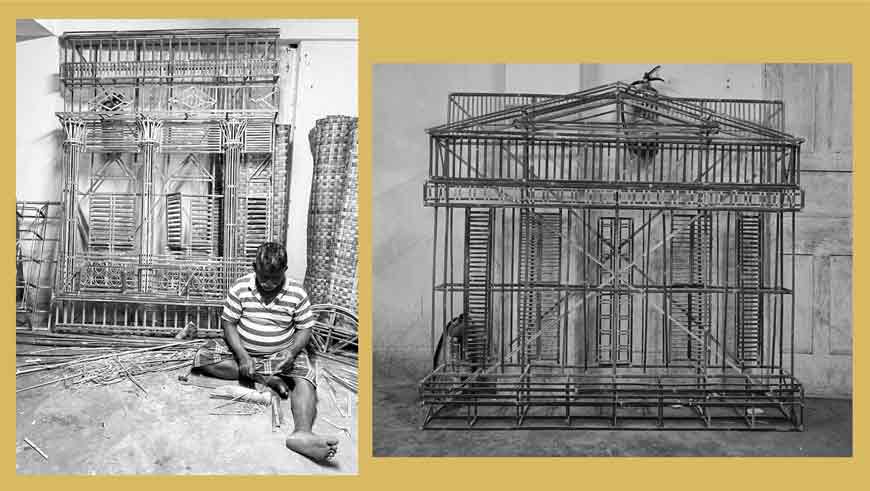

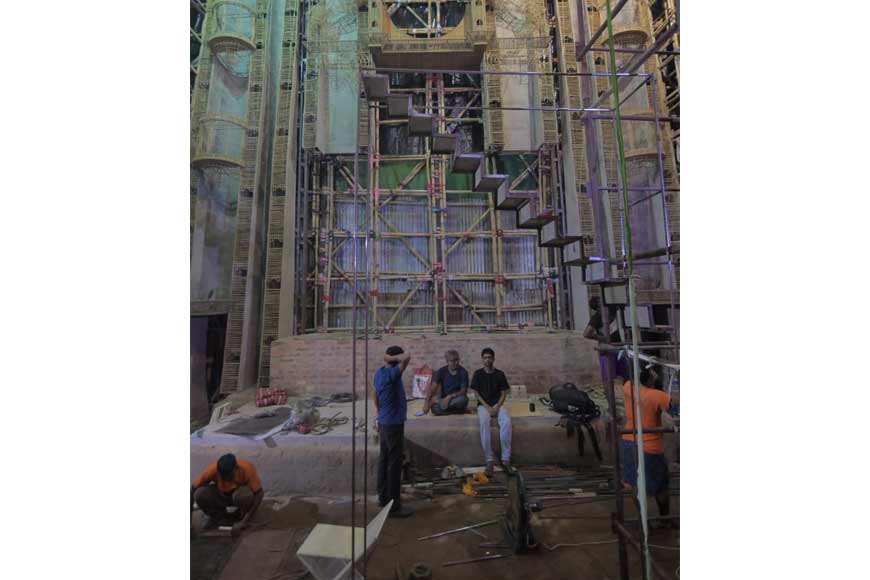

A team of 70 has been working under him, 24/7, since 14th June; with preparations going on in three different venues of the locality which has now finally converged in the pavilion, in time for the actual celebrations.

The Pandal

At the entrance, Lord Ganesh (a replication of a famous woodcut print) welcomes you. On the right, a train takes you, as it were, from Hatserandi to 19th century Kolkata; to a mansion where dancing girls perform on the ground floor while women of the house watch the show from behind curtains above. A band of musicians play live music, bringing 19th century into the 22nd. A massive Rath is what you see next, placed by the side of the trio of Jagannath temple – Jagannath, Subhadra and Balaram. But before you are quite done marveling at the beauty of the Rath (another vehicle through which gods were made popular), you confront a gigantic Ravan, his ten heads wrapped around a 360 degree sphere of mushrooming clouds that jut up from a frighteningly robust body. At this point, you don’t realize that from the entrance, you have already unobtrusively come up five feet from the ground; and are now standing at the head of a ramp from where you can see the most beautiful goddess there can be. You walk down the ramp (with many other delectable elements on either side); and as you do so, like the panning of a camera, the vision of the goddess rises above you till you come in front of her divine presence – to pay obeisance, to seek her blessings. This is in stark contrast to the darshan of a protima in a temple (or, in fact, in most pandals), where all intense narration and viewing happens at the eye-level.

You are not conscious of this, but your entire viewing experience has been dictated by the vision of the designer, who however doesn’t clutter yours at any point. Though there is a lot going from entrance to exit, the design of the pavilion allows you to enjoy one element at a time. You are however left overwhelmed at the end of it all!

The Artist

Visiting the work-in-progress pandal of Purbachal Shakti Sangha thrice in five weeks, and witnessing the process of art-making as it unfolded in the last phase of the months-long work, has been one of the most memorable experiences of my life in my home city to date.

I recently read Tapati Guha-Thakurta’s In the Name of the Goddess: The Durga Pujas of Contemporary Kolkata (2015) – a fascinating study of the evolution of the Pujo and its public celebration in the city through its pandals. One of the key issues the book explores is how the puja pandals, especially in the new millennium, have redefined the concept of the artist and what constitutes art in Kolkata. An interesting moment in that evolution was the ‘Artist’s Puja’ of Bakulbagan. In 1975, in a departure from usual practice, artist Nirode Majumdar was asked to design the protima for their Puja by a senior resident. That began a tradition that continued for two decades, with many of Kolkata’s prominent artists – from Rathin Maitra and Paritosh Sen in the 70s to Bikash Bhattacharya, Shyamal Dutta Ray, Meera Mukherjee and Shanu Lahiri (among others) contributing to it in the 80s and 90s. In 1992, the Principal of the Government College of Art, Isha Mohammad, was invited to create the idol, in a gesture to look beyond communal divides in the wake of the Ramjanmabhumi agitation in the country. While working, Mohammad assigned the painting of the idol to a young BFA student of the College, specializing in ceramics. That student was Partha Dasgupta!

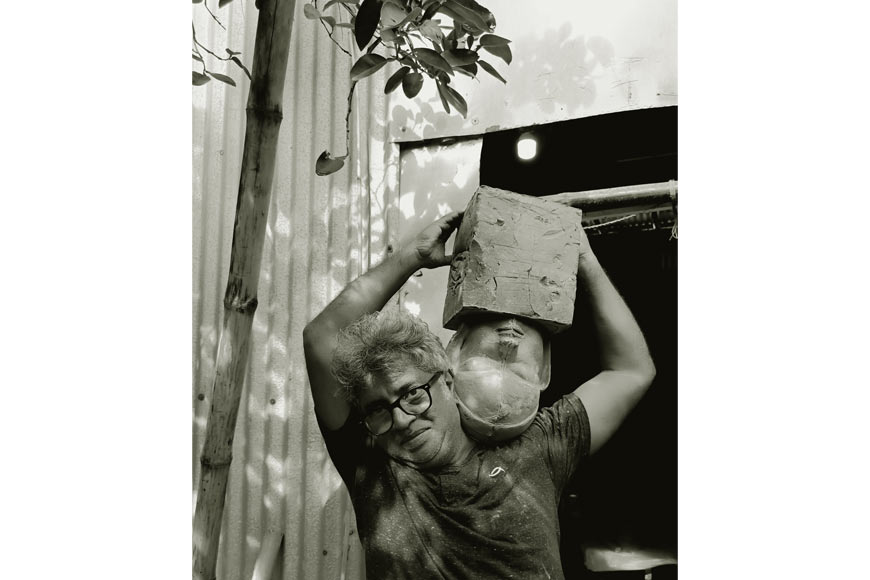

Partha Dasgupta, artist behind the Durga Puja Pavilion in Kolkata

Partha Dasgupta, artist behind the Durga Puja Pavilion in Kolkata

Dasgupta recalls that moment of initiation with a smile, in my first visit to the under-construction pandal. Subsequently, he shares the long trajectory of his pujo career with me. It really took off with Barisha Sakti Sangha in 2001 (-2004); continued with Behala Adarsha Palli (2005); re-started after a gap with Khidirpur Pachis Palli (2012); followed by Rajdanga Naba Uday Sangha (2013-2014); Vivekananda Athletic Club (2014-2015); Behala Natun Dal (2016, where Jayashree Burman had done the protima); and Thakurpukur State Bank Park, this last being the longest stint (2017-2022). Between 2007 and 2011, he assisted in making films on Durga Puja and did a lot of archiving of the Pujos of Kolkata. This gave him an overall better sense of the Pujo experience from the perspective of the audience, which became an added advantage in his later work.

Dasgupta agrees that he is part of a decisive shift from the late 90s, where institutionally trained artists brought, as he says, “a conscious addition to the tradition of idol-making and especially pandal-design”, with the architectural aspect of the design gaining ever more prominence. He is generous in his praise of fellow artists who have made their mark in the field: admiring Bhabatosh Sutar for his all-round editing and for being what he calls methho (of the soil); Sanatan Dinda for being more experimental in his approach than others; and Sushanto Pal for his cinematic conceptualizations. That so many of them have been active at the same point is, according to him, because pandal-design has emerged as a viable alternative source of income for the artists. And they are continuing with it because they are able to work with creative freedom.

Dasgupta is a man whose memory is rife with anecdotes, as I was to discover during our conversations. Many of the Pujo-related ones have to do with Asian Paints. When they had first instituted ‘Sharad Samman’ in the mid-80s, they had invited poet Subhas Mukhopadhyay to give the tagline; and he had come up with the inimitable copy: Suddho suchi, sustho ruchi’r, shera bachhai. (‘The best selection of refined sensibility and taste’, in Guha-Thakurta’s translation). Dasgupta loves this tagline; and as a veteran recipient of the award can be said to be the torch bearer of that aesthetic principle governing the selection of winners.

The completed protima of Purbachal Shakti Sangha

The completed protima of Purbachal Shakti Sangha

But he is wary of claiming the spotlight for himself. In every venue of the preparations – the huge pandal under progress; the neighboring drama club premises where the bamboo installations are being prepared; and his own home where he has been sculpting the protima – he introduces me to his many collaborators and assistants, and marvels at their specialist work. Work that he archives both in the form of a book and a documentary every year. Notable among the former is Durga: The Making of Becoming (2012); and among the latter, Tilottama (2014).

Conversing with him, while he is at work is both instructive and enriching: enriching for his almost encyclopedic knowledge of the history of the Durga Puja, various facets of which he elucidates upon (in answer to my questions) with a seasoned teacher’s patience and eloquence; and instructive, for the casual efficiency with which he orchestrates a mammoth and multi-pronged effort.

Do visit the spectacular manifestation of that effort at Purbachal Sakti Sangha – if in Kolkata during the Pujo.