The larger than life aura, Netaji’s enduring legacy

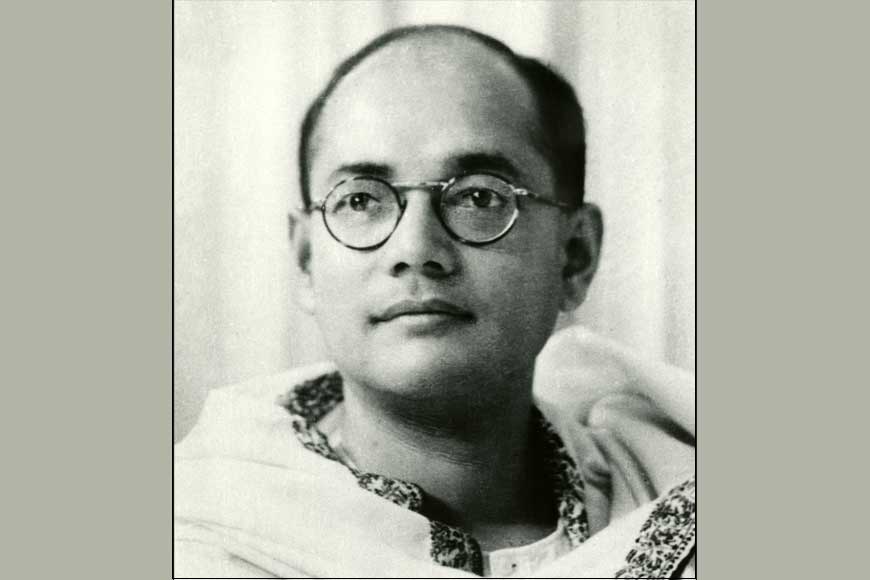

“His romantic saga, coupled with his defiant nationalism, has made Bose a near-mythic figure, not only in his native Bengal, but across India.” So say authors Barbara and Thomas Metcalf in their 2012 book ‘A Concise History of Modern India’, talking, of course, about Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose.

No other Indian freedom fighter, much less one from Bengal, has acquired quite such an aura. History enthusiast and essayist Somen Sengupta, who has written extensively about Netaji, says, “The superhero status that Subhas Chandra Bose enjoys among not just Bengalis but Indians as a whole is probably chiefly because he doesn’t fit into a Bengali stereotype.

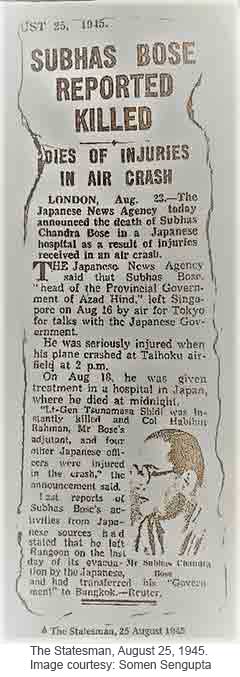

This ‘near-mythic’ quality has persisted through the decades after Netaji’s apparent death in an apparent air crash in what was Japanese Taiwan in 1945. Indeed, his mysterious death (some still refer to it as a disappearance) is no small part of that myth. And it is this that has caused a proliferation of theories, speculations, legends, books, films, and art ranging from matchbox covers and calendars to ‘respectable’ paintings. In most cases, the hero worship has transcended what numerous scholars have called a troubled legacy.

This ‘near-mythic’ quality has persisted through the decades after Netaji’s apparent death in an apparent air crash in what was Japanese Taiwan in 1945. Indeed, his mysterious death (some still refer to it as a disappearance) is no small part of that myth. And it is this that has caused a proliferation of theories, speculations, legends, books, films, and art ranging from matchbox covers and calendars to ‘respectable’ paintings. In most cases, the hero worship has transcended what numerous scholars have called a troubled legacy.

No other Indian freedom fighter, much less one from Bengal, has acquired quite such an aura. History enthusiast and essayist Somen Sengupta, who has written extensively about Netaji, says, “The superhero status that Subhas Chandra Bose enjoys among not just Bengalis but Indians as a whole is probably chiefly because he doesn’t fit into a Bengali stereotype. Bengalis are supposed to write poetry anyway, so naturally we have a Rabindranath Tagore; they are good speakers and born philosophers, so we have Swami Vivekananda. But a young Bengali man who escapes to Afghanistan in the dead of night; then uses a fake Italian passport to travel to Moscow; from there to Germany, where he stays in Berlin for more than a year, then travels for more than two months in a German submarine to Madagascar; then leaps onto a Japanese submarine, which takes him to Indonesia; from there he catches a plane to Tokyo, and then the Japanese government facilitates his visit to Singapore, where he reorganizes a 45,000-strong militia, and removes the headquarters to Burma. Finally, when defeat seems imminent, he travels to Taiwan via Bangkok. After which, we don’t really know whether he died en route, or escaped to Russia.”

A Ganesh idol during Ganesh Chaturthi in Maharashtra, 1946. Image courtesy: Somen Sengupta

A Ganesh idol during Ganesh Chaturthi in Maharashtra, 1946. Image courtesy: Somen Sengupta

The attempted alliances with Japan and Germany, which have contributed in great measure to Netaji’s sometimes controversial legacy, have never really impacted his status in the public mind.

This breathless, headlong journey, adds Sengupta, is something straight out of a Hollywood production. “His political mistakes may have been numerous, and his life is a story of missed opportunities at the national level in India, but for sheer dynamism, he has no comparison. He remains the only top-ranked Indian leader of his time, and I include Nehru and Patel, who repeatedly risked his life in his efforts to overthrow the British,” he says.

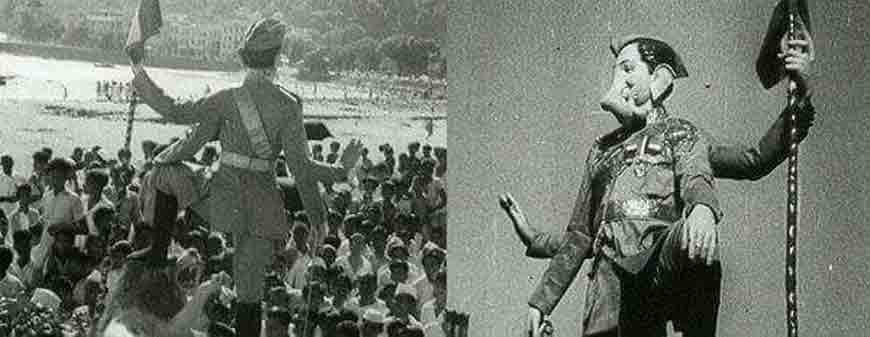

The attempted alliances with Japan and Germany, which have contributed in great measure to Netaji’s sometimes controversial legacy, have never really impacted his status in the public mind. Research scholar Soumya Basu, who is working on a book on Netaji to be published this year, feels a lot of this is also owing to the way Netaji appeared in public, once he had embarked on his solo mission to free India. The quasi-military costume, the impassioned speeches, the call to outright war against the imperialist British, all of this contributed to the popular impression of him as a crusading hero.

Outside of Bengal, how does the rest of India view Netaji? Sengupta mentions an occasion in 1946, when an idol of Lord Ganesh was sculpted to look like Netaji on the occasion of Maharashtra’s famed Ganesh Chaturthi. No other contemporary leader enjoyed that kind of public adulation. Basu points out that in 1945, as India learnt of the Indian National Army (INA), people got together to observe ‘INA Diwas’ in a remote corner of Rawalpindi, which went to Pakistan post-1947. “The entire subcontinent was inflamed with the idea of the INA,” says Basu. “In terms of political maturity, I would probably place Chittaranjan Das ahead of Netaji. But no other leader from Bengal has enjoyed the kind of national acceptance that Netaji gained. I have seen this in areas ranging from Punjab to Maharashtra to Tamil Nadu to Kerala. It wasn’t just about politics, he had successfully created a larger than life image.”

This year marks Netaji’s 125th birth anniversary. From the daredevil student of Presidency College who reputedly threw a villainous professor down a flight of steps, to the daredevil who disguised himself as a Pashtun insurance agent called Ziaudddin to reach Afghanistan, where he became the Italian nobleman ‘Count Orlando Mazzotta’, the sheer theatricality of Netaji’s life and career, and even his death, is what has kept the legend alive. Apart from the scholars who have written about his life, very few members of the general public have let facts get in their way.