The earliest Bengali prose in print, with a touch of Portugal

When you consider the history of Bangla prose, how many of you think of the name Dom Antonio de Rosario? A Portuguese name, evidently, though the man behind the name was purebred Bengali. The son of a rich landowner in Jessore in what is now Bangladesh, who was captured and imprisoned by the Portuguese, and converted to Christianity.

This account in itself would probably be worth a book, but add to that the fact that Dom Antonio was the first writer of Bangla prose, and nothing short of a book and a film will suffice.

Of course, for history aficionados, the story of a Bengali man in a Portuguese prison may not seem that far out. Most of us tend to equate the Portuguese presence in India only to the state of Goa, quite forgetting that they were the first Europeans to arrive in India, and it was their success which, in part, inspired the British to try their luck.

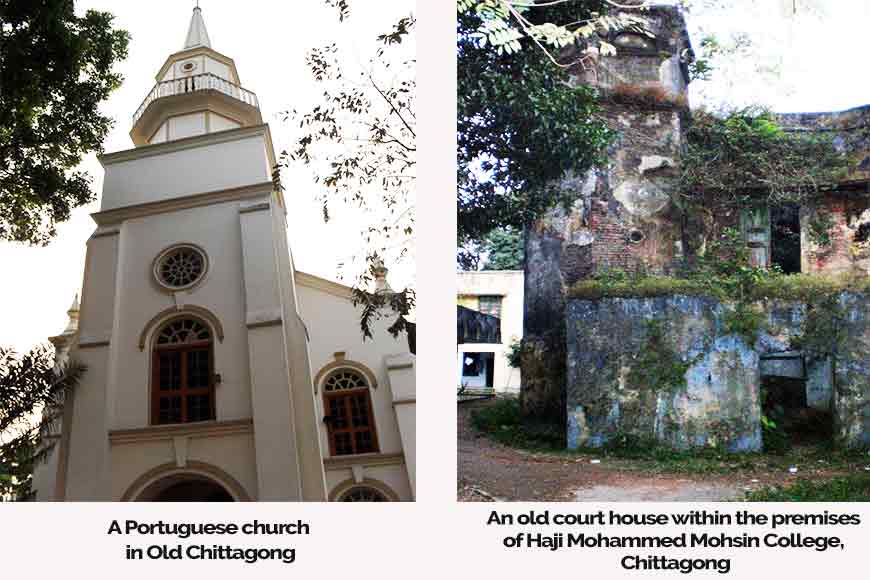

Considering that Goa on the west coast is one of the strongest remnants of India’s Portuguese era, it is rather ironic that when they first arrived, Vasco da Gama’s countrymen focused primarily on southeastern and eastern India while building their settlements. Many of them achieved particular notoriety as harmad, or river pirates. As a result, large chunks of modern-day Bangladesh came under Portuguese control, and many splendid examples of their architecture (churches among them) remain scattered across Bangladesh today.

Of course, architecture was only part of the story. The Portuguese also brought with them what were then exotic fruits, flowers and plants, which have become such an intrinsic part of our existence that we no longer even stop to think about their origins. Simply think of life without potatoes, cashew nuts, papayas, pineapples, kamranga (carambola), guava and the Alfonso mango, to give just a few examples, and you get the picture.

Inevitably, too, as the two languages intermingled, numerous Portuguese words or their derivatives, e.g. chabi, balti, perek, alpin, and toaley became permanent members of the Bengali vocabulary.

Which brings us to Dom Antonio, whose birth name has been lost in the mists of time. This much we do know, that he was born in 1643 into a prosperous family of Bhushona, Jessore. When he was around 20, he was abducted and imprisoned by Portuguese pirates, to be sold as a slave in Arakan (known today as Rakhine, in Myanmar). Rescued by Portuguese priest Manoel de Rosario, the young man sought refuge in Christianity, and went on to become a missionary himself. Thus was ‘born’ Dom Antonio de Rosario.

By 1666, Dom Antonio had returned to his birthplace and was preaching Christianity, which he continued until his death in 1695. Soon, several members of his family, as well as the tenants on their property, had converted to the new religion. As his influence and the sphere of his proselytization grew, Dom Antonio founded the St Nicholas Tolentino Church and Mission in Kosh Bhanga village, which were later transferred to Nagori village in Bhawal district.

Through all of this, he kept up efforts to make the teachings of Christ more accessible to his Bengali brethren, in written form. He was aided in his task by his adoptive Portuguese brothers, who displayed quite a bit of interest in the Bengali language themselves. It is said that as early as 1599, a missionary named Father Sosa translated a religious tract into Bengali, though no copy survives today.

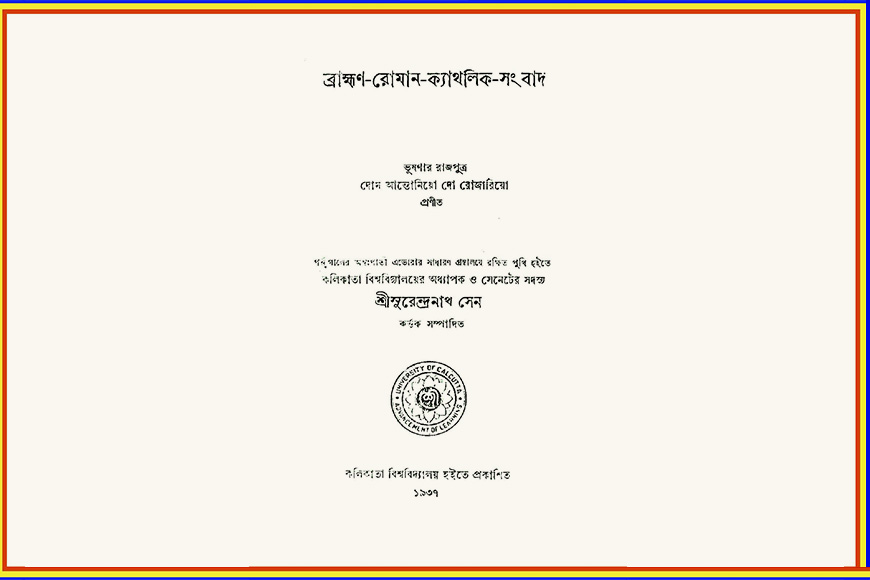

What we do have is Brahman Roman Catholic Sambad, Dom Antonio’s 120-page tract which features a Brahmin and a Roman Catholic in conversation about the relative merits of their faiths, whereby Christianity is ultimately established as a superior belief system. Some scholars have ascertained that the book was translated into Portuguese by Antonio’s fellow missionary Manuel da Assumpção, and published by Fransisco Da Silva from Portugal’s capital Lisbon in 1743.

However, for us, the more relevant publication would be the one edited by Prof. Surendranath Sen and printed from the University of Calcutta in 1937. To this day, it remains the earliest surviving example of Bengali prose in print. A lot of that prose is very similar to what we have today, and the complexity of the subject matter is testament to Dom Antonio’s skills as a communicator and writer.

Incidentally, the first Bengali-Portuguese and Portuguese-Bengali dictionary, comprising 529 pages, was also written by Assumpção, who was also responsible for a 40-page pamphlet on Bengali grammar.

That the general Bengali reader had to wait until 1937 to read a book written in the late 17th century and first published in the 18th century, is perhaps our biggest takeaway from this saga.