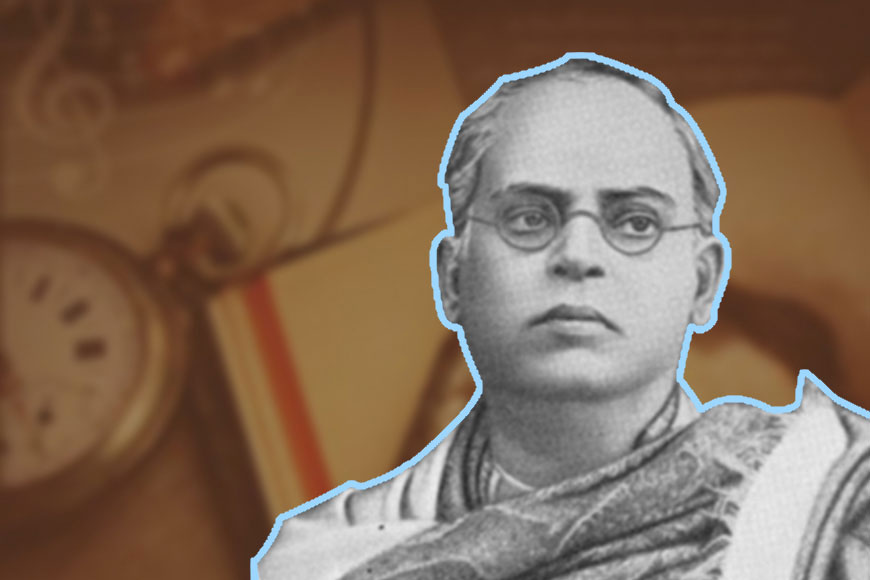

The Dwijendralal we never knew

‘Sottyo Seleucus! Ki bichitro ei desh (truly Seleucus, what a strange land this is)!’ This line has become all but a proverb in Bengali, one we see used almost every day without really thinking about the source. The truth is, this is a line from ‘Chandragupta’, a play by Dwijendralal Ray, which very few of us remember, or even know. On his 160th birthday today, it is perhaps time we looked back at a man who ought to be regarded as a multi-faceted genius, not just as the creator of ‘Dhonodhanyo Pushpo Bhora’.

Born to Kartikeya Chandra Ray - a dewan of the Krishnagar royal family and a renowned singer and writer - and Prasannamoyee, Dwijendralal’s childhood was filled with literature, music, and the arts. Indeed, he began writing songs as early as the age of 12, having taught himself how to play the harmonium at the age of six or seven. In years to come, as he matured into a poet, lyricist, composer, and dramatist, comparisons became inevitable with Rabindranath Tagore, his senior by two years.

Sadly, the one other thing that ‘Dwiju Ray’ is remembered for, is his supposedly strained relationship with Tagore, which had its origins in a few acerbic comments and writings by Ray, influenced by a group of trouble mongers. One examople would be the satirical play ‘Ananda Biday’, obviously mocking Tagore. So strong was the popular reaction against the opening performance of the play that Dwijendralal had to sneak out of the auditorium through a stage door. In later years, he openly expressed his regret about these writings, most notably to his son, Dilip Kumar Ray.

The creator of over 500 songs in his lifetime, Dwijendralal nevertheless continues to be remembered only for a handful, such as ‘Dhonodhanyo Pushpe Bhora’ and ‘Oi Mahasindhur Opar Theke’. Public memory has largely forgotten his songs of love, comic songs, and patriotic lyrics. Tragically, the notations of a mere 130-odd songs are still available to us. His 21 plays belong to such varying genres as history, satire, mythology, and social issues.

That apart, as a deputy magistrate in Medinipur, he put his degree in agriculture to good use as he reduced the taxes imposed on farmers, placing him in direct opposition to the British-Indian administration. Simultaneously, he became ‘Dayal (merciful) Ray’ to local farmers, though the incident forever scuppered his chances of promotion. Not that he minded, having openly written about his delight at the relief he had managed to bring to the farmers.

Having gained an interest in Western music during his years abroad studying agriculture, Dwijendralal applied the knowledge to his distinctive brand of music, in which he proved as adept as Tagore. Following the partition of Bengal in 1905, he came up with a couple of plays such as ‘Pratap’ and ‘Mewar Gourob’, the latter influencing no less a personage than Acharya Jagadish Chandra Bose, who requested Dwijendralal to write a song about prevailing Bengali sentiments. Thus was created ‘Bongo Amar Janani Amar…’.

Nationalist, musician, poet, Dwijendralal wore many hats with ease. Time we restored him to his rightful place in the pantheon of the icons of Bengal.