The district council strives to revive Birbhum’s Serpai – GetBengal story

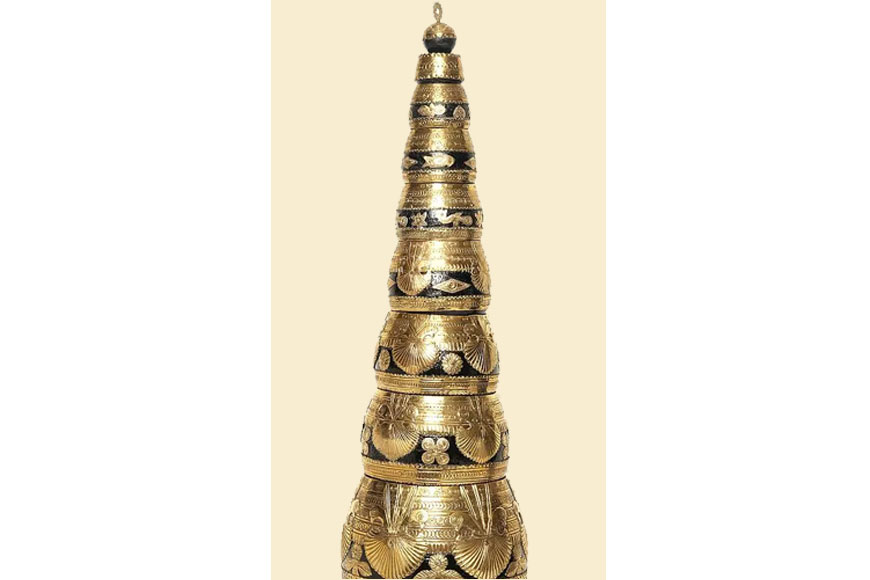

Ancient Indian systems of measurement often used vessels to measure grains for trading. These measures were known by different names, depending on the region. Serpai, Kunke, or Paila were containers made of cane or metal used to measure grain in India. In the north, these measuring cups were called "ser" or "sher," whereas in the south, the unit was called "padi." Pi comes from the word 'poa'. Ser and Poa are units of measurement, which are referred to as serpai, colloquially. It was only later, during the British Raj, that modern systems of weights and scales were introduced. Although, with the passage of time, the serpai lost its practical application, in rural areas of India, one can still come across vendors selling grains and peanuts by measuring with a "cup" (serpai or kunke) instead of weight. The serpai has now become a piece of flair or a prized collector’s item. Connoisseurs of art collect them as exquisite pieces of art.

In the past, Bengal’s wooden serpai was renowned for its craftsmanship and widely used throughout the country. Not only was the measure a functional item, it was also admired for its amazing artistry. However, over time, serpai has lost its functionality and its former glory. Those artisans who traditionally made these serpais moved on to other trades as demand for the product decreased. However, a single family from Lokpur, or ancient Lakshipur village near Khoirashol in Birbhum district, is still struggling to keep the ornate serpai or Suri bowl art alive. It is a pity that a majority of us are not even aware of indigenous art and its creators.

Lokpur is a tiny village in Khoirashol in Birbhum district, bordering the state of Jharkhand. The village is a part of the ancient Chota Nagpur Plateau, something that was formed more than 540 million years ago by continental uplift from forces acting deep inside the earth. This marginal village is renowned for its serpai manufacturing industry. Kamalakanta Karmakar, a local resident, set up this cottage industry in Lokpur in the 1940s. He was a deft artisan who broke free of the previously used means of measuring 'Ser' and 'Pi' and recreated a different and more accurate form of the measure that was also aesthetically pleasing. The brass work on wooden sers and pies that he introduced was highly appreciated, and his serpai became commercially successful as well. Karmakar received the President's Award in 1965 for his decorative creations. Since then, three generations of the Karmakar family have been making a living out of manufacturing these decorative Serpai pieces.

Kamalakanta Babu’s grandson, the late Kartik Karmakar, could not continue the work due to advancing age and failing health. On the other hand, Kartik Babu's two sons were unwilling to be part of the family-run manufacturing business. Finally, his disciple and son-in-law, Bholanath Karmakar, along with his wife, Ruma Karmakar, Kartik Babu’s daughter, took up the mantle, and since then, they have been totally involved in the niche art of serpai manufacturing. They have proved themselves worthy successors to Kamalakanta so far.

Serpai is made of wood, iron, and stone. The basic wooden framework is made first, and then an iron or brass sheet is placed on that wooden structure. Intricate designs are carved on the sheet, and finally, the serpai is painted and polished. Familiar ornamental motifs carved on the serpais include sunflowers, fish, conches, and insects. The serpais are painted with natural colours like lamp black or soot made at home.

With each passing year, the apprehension of the indigenous art of serpai manufacturing vanishing with Bholanath and Ruma’s retirement has been increasing. Their progenies are not eager to join the profession. As the possibility of this art vanishing eventually increased, Mohammad Israr, the then-BDO of Khoirashol, took the initiative to save the traditional art. It was his idea to get a photograph of the endangered art of Serpai on the cover of the official diary of the Block in 2013. He discussed this with district officials and initiated a training scheme for members of local self-help groups to save the industry.

In order to save the endangered cottage industry, the administration started a programme to train members of Mahila Swanirbhar Dal to make serpais professionally. Prominent serpai artist Bholanath Karmakar trained 23 women from various self-help groups for one month. His wife, Ruma, assisted him in the training camp. According to the artist couple, there is a demand for the finished product (serpai) we make, but it is not possible for a family to produce large quantities of serpai and fulfil the demand in the market. In this scenario, if the government trains female members, both parties will benefit.

The products manufactured by trainees at the training camp were exhibited at various fairs, like Sabala Mela, and the response was positive. Since then, the Birbhum District Administration, in association with the Block Administration, has organised this training camp annually. The aim of this entire project is to save Birbhum’s indigenous 'Serpai' art from extinction. There is hope that the project will not only help rural women achieve self-reliance but also save traditional art from disappearing.

Incidentally, Aditya Mukhopadhyay has researched and written in detail about this traditional folk art form of Birbhum in his book, 'Serpai Shilpa' of Lokpur’. Tilak Purkayastha's 'Banglar Lokshilpa: Shilpa O shilpir Sondhane’ (Bengal Folk Art: In Search of Artists and Art) and 'Kopai Nodir Kada Paye’ (With Muddy Feet of Kopai River), both present a detailed study of the indigenous arts of Birbhum, including the serpai. 'Kopai Nodir Kada Paye’ was edited by Malay Mukhopadhyay and published in 1991 under the aegis of Bolpur-based Akhil Bharat Bhu-Vidya O Porisbesh Samiti.