The day Rabindranath became immortal

It is the 22nd day of Shravan, 1941 - clouds are gathering all around, like frozen tears. A sea of humanity engulfs Upper Chitpur Road, Vivekananda Road, Chittaranjan Avenue, Kolootola Street, College Street, Cornwallis Street, Grey Street, B.K. Paul Avenue, and then on to Nimtala. As the tears flow, so the streets and lanes and bylanes are carpeted with bouquets of flowers, and garlands. Khoi and rosewater descend on the city like leaden despair, enveloping the streams of mourners in gloom. Unable to contain his emotions, the poet Jatindranath Sengupta writes:

“দূর হতে কানে আসছে

বিপুল পরাজয়ের তুমুল জয়ধ্বনি!

সহসা দেখা গেল

মরণের কুসুম কেতন জয়রথ!

কি বিচিত্র শোভা তোমার

কি বিচিত্র সাজ!”

(From a distance I hear

The wild cheers of an immense defeat

Suddenly I see

Death’s victory chariot, its flowery ensign

What strange beauty is yours

How strange your adornments!)

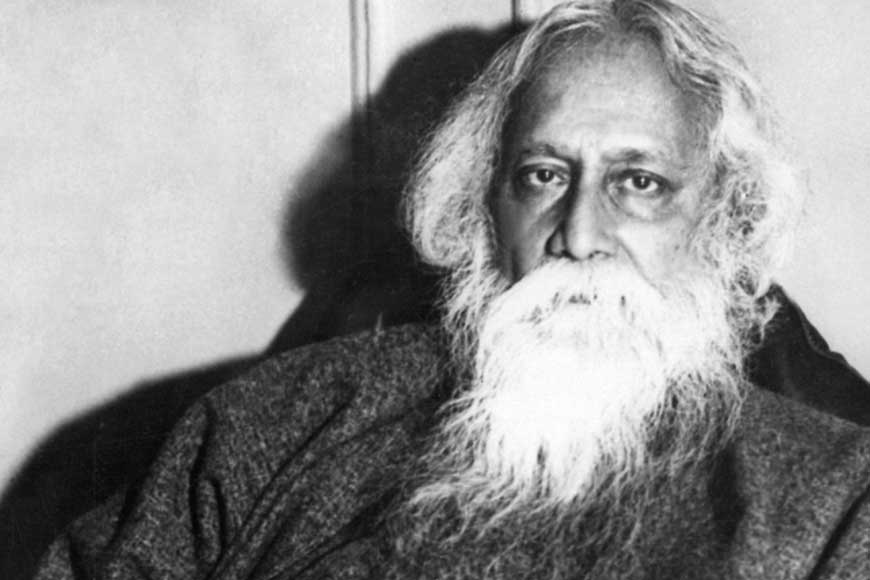

The ‘wild cheers’ roar out like thunder, as though mocking the sharpness of collective sorrow - incongruous cries of ‘Rabindranath ki jai’ or ‘Vande Mataram’. The man at the heart of it all is the only one completely unaffected by the chaos. Rabindranath has found eternal sleep, death has come to him as Shyam, the dark god he wrote about in ‘Marana re tuhu mama, Shyam saman’ (O Death, you are like my Shyam).

As one used to the interplay of life and death from almost the beginning of his days, physical death probably came as a relief to him. The mortal remains which reached Nimtala Ghat at 5.40 pm, and then spread across the universe as immortal memories, were never really destroyed by death. Death knelt before him, the truly deathless one.

In one of her letters, Hemanta Bala Devi had once asked him whether he feared death. Rabindranath had replied by equating death with sleep, saying how sleep made wakefulness bearable, in the same way that death came to us as a relief from unending life. Inseparable entwined as it is with life, death should be accepted as a matter of easy faith. He had also once told Amiya Chakraborty that in order to truly view life, we should use the prism of death. It was only he who could imagine death as a beloved, wedded to him in the strong bonds of marriage.

On September 10, 1937, a sudden attack of erysipelas robbed Rabindranath of consciousness for nearly 50 hours. He had been narrating a story, sitting on the balcony. As a chilly wind struck up, he moved indoors, and lost consciousness. A team of doctors led by the redoubtable Nilratan Sircar had snatched him from the jaws of death then, which he celebrated with the lines:

‘আসন্ন মৃত্যুর ছায়া যেদিন করেছি অনুভব/ সেদিন ভয়ের হাতে হয়নি দুর্বল পরাভব।’

(I sensed the shadow of death that day/ But did not give in to fear, come what may)

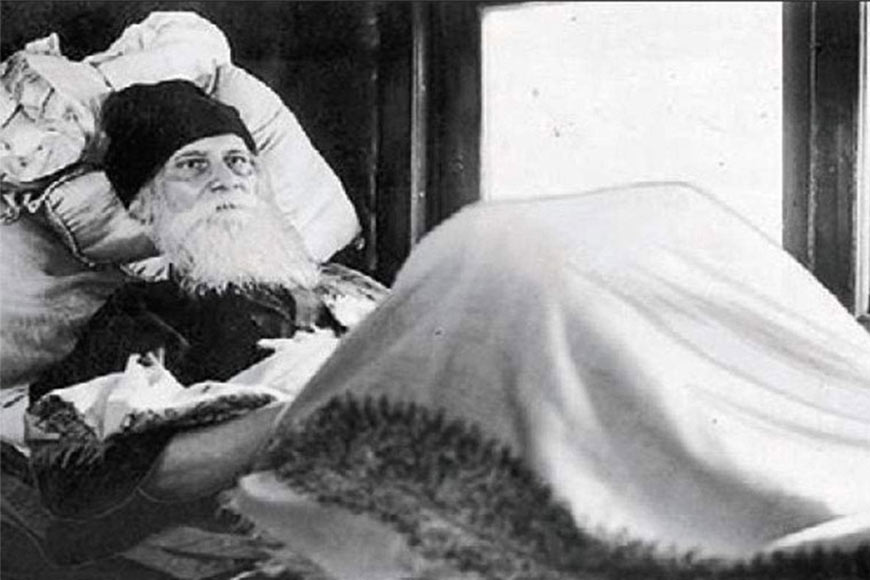

In Kalimpong on September 25, 1940, he went through the same experience all over again. An English civil surgeon stationed in Darjeeling wanted to operate on him immediately, but a team of physicians from Kolkata brought him back to his city with infinite care. However, that was the end of normal life as he knew it. He was never to return to its familiar rhythm.

In the midst of it all came Bhaiphonta, and his sister Barnakumari Devi’s thin, trembling finger etched the mark of chandan on his forehead as he lay bedridden. We find a riveting description of this, Rabindranath’s final Bhaiphonta, in the writings of Rani Chanda.

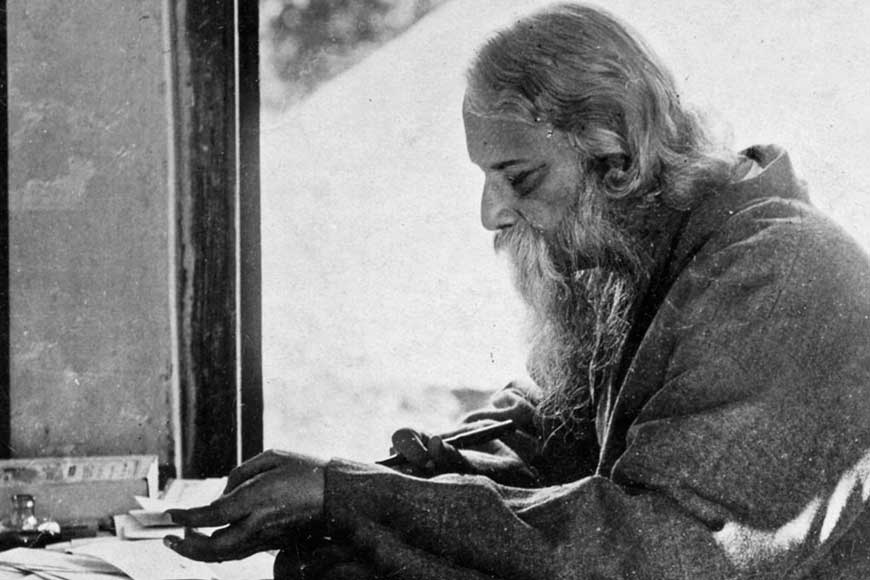

After this, he was transported back to Santiniketan, and housed in the Japanese Room. Transcending his physical agony, he was even then producing such cheerful nonsense as ‘Golda chingri tingri mingri’, and publishing poems like ‘Rogshojyay’, ‘Arogya’, and ‘Janmadine’, and experimenting with novel narrative techniques in ‘Tinsongi’ and ‘Golposolpo’. Despondent at his inability to participate in the Poush Mela festivities beginning on the seventh day of Poush, he dictated his inaugural speech to Amiya Chakraborty.

Despite these hectic days, he was clearly preparing for the longest journey of his life. Lightly, he wrote:

“সময় হয়ে এল এবার

স্টেজের বাঁধন খুলে দেবার,

নেবে আসছে আঁধার যবনিকা।”

(The time nears

Unfasten the stage,

The dark curtain descends)

When the poet Buddhadeb Basu paid a visit, Rabindranath spoke to him for a solid hour, practically without stopping. Basu would later write, “This man is ill! Unthinkable!” The outcome of their conversations were two essays - ‘Sahitye Oitihasikota’ and ‘Sahityer Utsa’.

The torrent of work was sweeping his illness away, and he flatly refused to be operated upon. “I’m a poet,” he joked. “I want to go like a poet - drop off the earth as easily as leaves from a tree. Why cut me up before the journey? All this cutting and stitching and cutting again… best to return me to the earth in one piece.”

Nonetheless, the doctors had to try one last time. And so Rabindranath left Santiniketan for Kolkata for the final time. On July 27, he recited these lines to Rani Chanda:

“প্রথমদিনের সূর্য

প্রশ্ন করেছিল

সত্তার নূতন আবির্ভাবে—

কে তুমি!

মেলেনি উত্তর——”

(On the first day, the sun

Asked a question

Of the newly arrived soul -

Who are you!

There was no response...)

He wanted to hear his own poem ‘Bipode More Rokkha Koro’, calling the words of the poem a mantra, a prayer. A poem on July 29 seems like a harbinger of death:

“দুঃখের আঁধার রাত্রি বারে বারে

এসেছে আমার দ্বারে—!”

(The dark night of sorrow/ Has repeatedly come to my door…)

On July 20, some deep inner realisation prompted the last poem he ever wrote:

‘তোমার সৃষ্টির পথ রেখেছ আকীর্ণ করি/ বিচিত্র ছলনাজালে হে ছলনাময়ী।’

(O deceiver, the path of your creation is strewn/With the mosaic of your deception)

Despite his immense suffering, he had a letter written for Pratima Devi, signing it with trembling hands, the last signature of his life. Then came surgery, the delirium of illness, agony. As a Rakhi Purnima moon rose in the sky, the physical world finally surrendered its control over him. As dawn broke on the 22nd day of Shravan, August 7, the devotees began to gather, their offerings of champa flowers piling up at his feet, the song ‘Ke jaye amrita dham jatri’ (who is it who travels to the immortal realm) wafting out over the silent crowd. Somebody continuously whispers the timeless chant in his ear - ‘Shantam Shivam Advaitam’. And then, at 12.10 in the afternoon, it is as though the sun sets over Kolkata.

Rabindranath is on his final journey. Fittingly, he is dressed like a king, in a length of white benarasi. His dhoti is meticulously pleated, his silk panjabi, the scarf around his neck, the garlands of flowers, white lotuses and rajanigandha (nightshade), all perfectly in place. Even the cot bearing him to the ghat has been created by no less a personage than Nandalal Bose.

Who knows whether ‘Robi Thakur’ felt the insane tidal wave of sorrow and despair that crashed over the city that day, the unutterable, noisy grief of millions of citizens. But the magic of his creations ensured that the man who left for the immortal realm actually held immortality in his hands.

Who can talk of an end, when there is no end?

With inputs from: ‘Rabindranath, Rabindranath’ by Purnananda Chattopadhyay; ‘Baishey Shrabon’ by Rani Chanda; ‘Gurudeb’ by Rani Chanda