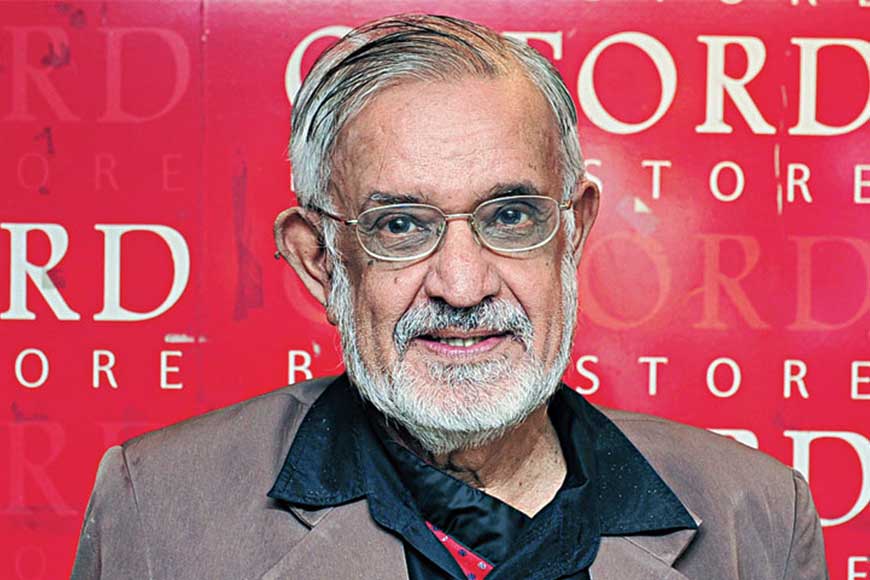

The boy from Kutch who hated working indoors

I knew Kishore Bhimani, long before we set eyes on each other. I lived in a world of sports, football and cricket where I discovered Kishore. There, and as the face of No. 10, and again falling in love with the welcoming voice at the Statesman Awards for Rural Reporting. I had, at that time, not even started dreaming of a job with the Statesman, leave alone thinking of hobnobbing with the likes of Kishore Bhimani, though his parents-in-law and my parents were rather close friends and fellow Rotarians.

When I did get to know him though, it had little to do with his voice or his broadcasts, it was more about Kishore the 'punter' on the bourses who would come across and check on stock quotations that I was getting ready to print for the next morning papers. What struck me -- as someone who took one's job very seriously -- was the insouciance with which Kishore treated his job. He came and went at will, sulked every minute he had to work indoors, typed out his copy occasionally on his desk, choosing to type elsewhere and only submitting it and generally growling about everything.

On the rare occasion, he would drop in for a few minutes at night to take a look at the sports headlines but he would invariably drop by at the commerce desk to see what insights we were providing on the corporate world, the economy and the market page, usually scoffing at our market analysts comments because Kishore always had an inside view of things on the trading floor. He knew better.

Regrettably, those days ended with Kishore getting promoted from Sports Editor to Assistant Editor, who was required to attend the "morning meetings". It was then that I found an ally in him Kishore would always oblige with an edit on international affairs and the third light edit that the Statesman was famous for and was finding it hard to address with the departure of Bachi Karkaria, Jug Suraiya and the redoubtable Sunanda Kishore Datta-Ray.

In his essence, Kishore was the Kutchi boy who had taken after his grandmother, who he considered to be a great storyteller and from whom he learnt about the great Indian mythologies, intrigued by Draupadi's polyandrous status, amongst others. Of equal influence on his life must have been the English sojourn, to study at the London School of Economics!

In his essence, Kishore was the Kutchi boy who had taken after his grandmother, who he considered to be a great storyteller and from whom he learnt about the great Indian mythologies, intrigued by Draupadi's polyandrous status, amongst others. Of equal influence on his life must have been the English sojourn, to study at the London School of Economics!

He never did talk about the education that he received but did confess to having lived the swinging sixties of London where, as he was to confess in a published conversation with his son Gautam, "nothing was forbidden", especially in the world of godmen, who were to appear in his latter day writing endeavours (The Accidental Godman).

"Among the things I was exposed to, there were these establishments that experimented with spiritualism and existentialism for people who were fed up with material life. They used a drug called mescaline, which was later made famous by Aldous Huxley in his book Brave New World. What they found was that the same experience yogis get with meditation you can get with mescaline. Mind you, all this was done by doctors. So it wasn’t underground".

My first hand experience with his story-telling abilities came when Kishore, Barun Das and I produced a spoofy column Bad to Bourse on the shenanigans of the corporate world. Our shenanigans on newsprint ended but there was always the occasional meeting -- one when we did not talk business but I taught him how to make a paper plane for his grandson -- , the occasional get-together at his place, the occasional comment on Facebook and the occasional phone call. There was nothing 'occasional' about Kishore though because once you got to know him, he would frequent your thoughts, whether you were commenting on the economy or talking disparagingly about its current managers or the plight of the dispossessed and, of course, talking about the environment. Breathe easy Kishore. There is no pollution up there.