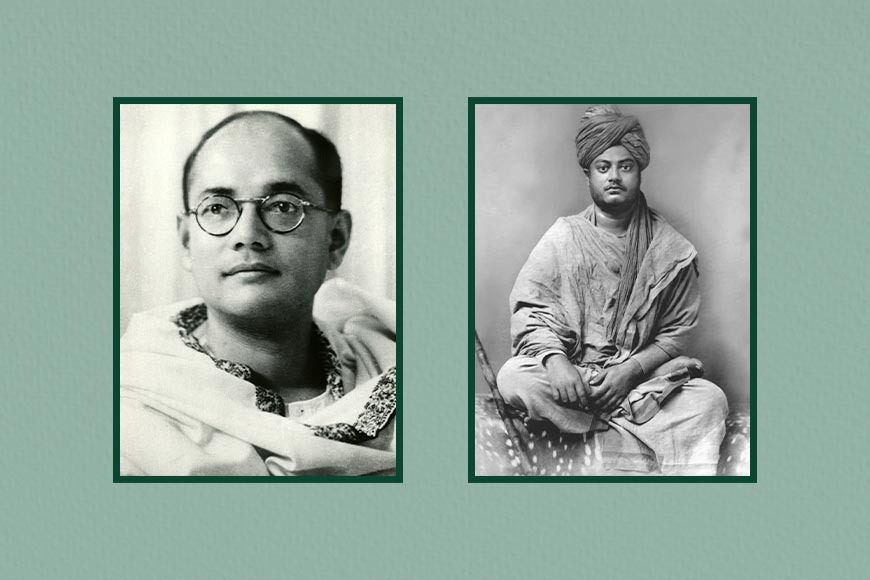

Swami Vivekananda influenced young Subhas Bose to fall in love with his motherland

The narrow lanes of Kiron Shankar Roy Road and Old Post Office Street are otherwise a mesh of old shacks serving a hot cuppa or bread omelets to hundreds of litigants, clerks, and lawyers who tread the footpaths every other day. These footpaths are also home to an odd dozen typists whose Remington machines still at times raise the staccato stuck sound. But the sounds are fading fast and so are the typists of the Calcutta High Court arena.

Take for example Gopal Shaw, a 65-year-old typist who operates from the footpath outside the Calcutta High Court. He has been sitting there every day for the last 30 years, but with a heavy heart, he acknowledges: “Our workload has diminished largely in the last two years of the Pandemic. As it is work was decreasing because of digitization, computers and laptops and the Pandemic is like a nail in our coffin.” Shaw is probably the last of the typists, a handful of whom still sit on the footpaths hoping to get work. “We hardly get any work nowadays. Once there were more than 50 typists in this area, now just a handful of us remain,” laments Shaikh Shahbuddin, who sits beside Shaw. “There was a time when we could not complete the workload and before taking the local train back home, tried to work extra hours, even under the candlelight during evenings. Now we wait for when someone will come with work. With the Pandemic, more and more cases are being filed virtually and there is literally no need for typists.”

In its order dated February 18, 2020, the High Court had directed that all pleadings contained in petitions, affidavits, and applications or otherwise and all memorandum of appeal shall be printed on A4 white executive bond paper instead of green or embossed paper. The court also fixed the size and space to be used in the paper while writing the documents. That meant a computer printout was the need of the hour. The judgment thus adversely impacted several hundreds of typists working outside various courts in West Bengal, not just the High Court. The court however permitted the use of typed legal documents provided they follow the new regulations. But the long-term aim is to digitize everything and go for e-filings.

There was a time when being a typist of any court was lucrative. Many of them even earned Rs 1,000 per day. Even for carbon copies typists were a big draw as in those days photocopies, xerox, etc. cost huge. But with several photocopy and computer printing shops mushrooming outside the High Court in recent years, typists realized their days are numbered.

Most of these typists landed every morning from districts availing of local trains. Lile Laljeeban Biswas comes every day from Hooghly. He wakes up early morning and cycles to the nearest rail station. He has been doing it for the last 25 years. But for Biswas also the High Court is no more a place to conduct business but a shelter house for senior citizens who have nowhere to go or start a new profession leaving back their typewriters. Their fingers still go strong, punching the keys and they seem to know the spellings of legal words under their thumbs. Their typewritten versions hardly show any errors, for they have been typing petitions, affidavits, caveats, and other court documents in English for decades. Some would even type letters sent to VVIPs. Even lawyers know the typists are vanishing fast. “Their profession needs to be protected, but then how?” asks Pallab Ghosh, a senior lawyer of Calcutta High Court. “There was a time when we would share a cup of tea with the typists and literally plead to complete our work before heading to the courtroom. That was the level of their busy hours. Today unfortunately most of them are out of business.”

As one of India’s oldest courts, the Calcutta High Court still holds sway over its colonial hangover, one wonders when will the clickety-clack of the typewriters fall silent and the struggle for survival come of Kolkata’s typists come to an end?