Subrata Mitra, the pioneer behind Ray, finally gets his due

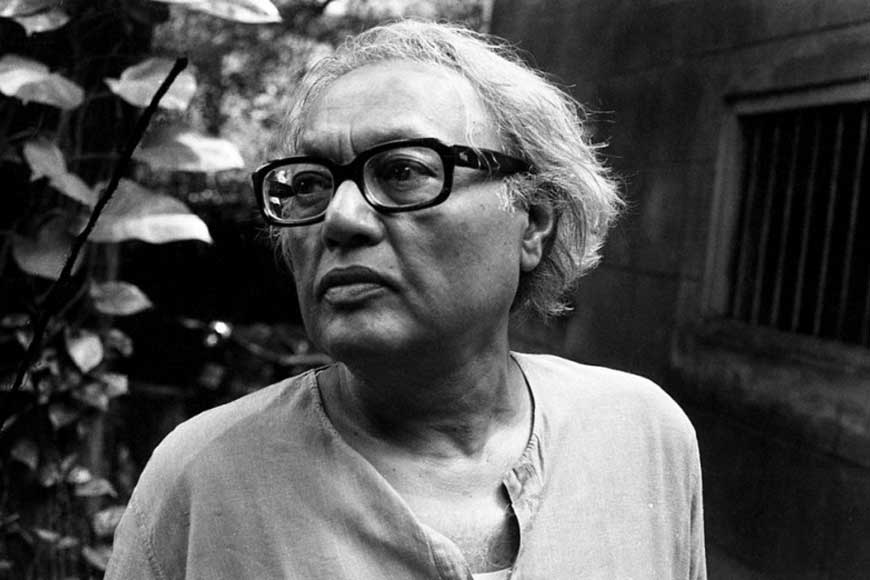

Subrata Mitra | Photo by Sanjeet Chowdhury

Subrata Mitra may have been one of Indian cinema’s most talented cinematographers, but the recognition he deserved came late in his life. And now, his ancestral home at 70, Sarat Bose Road will be granted heritage status as announced by the West Bengal Heritage Commission, but he is no longer alive to acknowledge this honour. Plans are also afoot to instal a blue plaque at the house next week, and create a museum there.

When a film makes history, its director attains immortality. The actors become famous. But the technical experts such as the cinematographer, editor, or art director, who contribute so much to the final product, often go unrecognized because they work behind the camera, away from the limelight. But one man reversed this tide through sheer genius, innovative skills, and an ability to maximise the minimal resources at his disposal. His name was Subrata Mitra, the cinematographer of Satyajit Ray’s epoch-making Pather Panchali.

Subrata Mitra (1930-2001) is perhaps the best thing to have happened to Indian cinema in terms of cinematography in every sense. He began his career with Pather Panchali (1955) and became known as the stormy petrel of Bengali cinema, forever involved in technical experimentation in every aspect of cinematography. Filmmaker Arindam Saha Sardar’s hour-long documentary on this talented, temperamental man also tells us that Mitra - a trained sitarist who was roped in by Jean Renoir for a scene in The River, playing the sitar both in front of the camera and behind it - was also a painter in his spare time.

Mitra made his first technical innovation while shooting Ray’s Aparajito (1956), a decade before Sven Nykvist, Ingmar Bergman’s classic cinematographer, was to do so. Mitra’s arguments with Ray and art director Bansi Chandragupta about the impossibility of simulating shadowless diffused light inside a studio in Kolkata were endless. When his arguments fell on deaf ears, Mitra invented what is now known as bounce lighting, which Nykvist later claimed to have innovated. Instead of using direct lighting to illuminate the set, Mitra placed a framed white sheet over the set to resemble a patch of sky and arranged the studio lights below this to bounce off the fake sky. The result was a simulation of soft, diffused, shadowless light, reflected from the artificial sky.

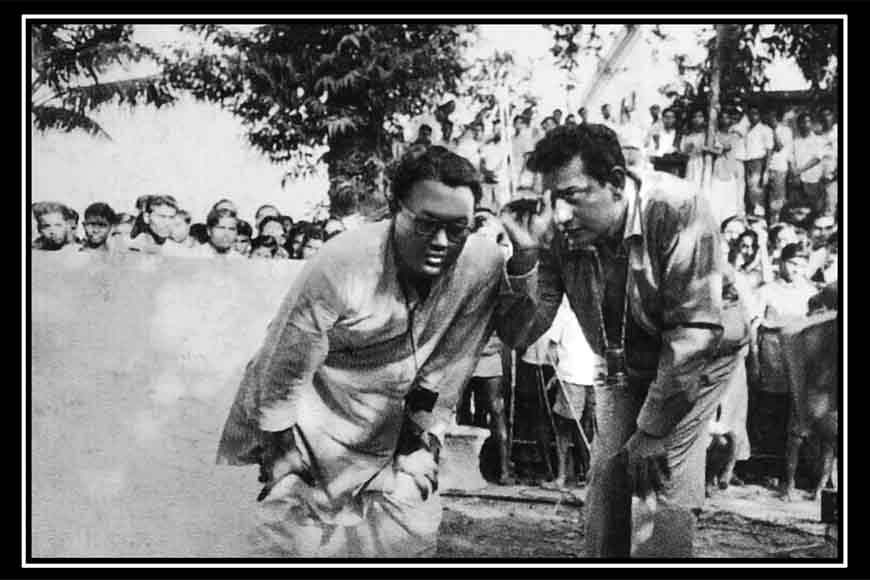

An interesting incident happened in Darjeeling during the shooting of Ray’s Kanchenjunga, his first film in colour. A team from Mumbai was shooting Lekh Tandon’s Professor (1962) at the same time. Dwarka Divecha, the noted cinematographer who later worked on Sholay (1975) was the cameraman. Hampered by the endless and unpredictable mist, the team had been stuck, unable to shoot for days. But when he saw Mitra calmly shooting Kanchenjunga in the same mist, a surprised Divecha invited him to his hotel room and asked how he was working in such whimsical weather. Mitra said it was precisely the misty environment that he wanted! Not surprisingly, Kanchenjunga remains a milestone for Eastman Colour.

Soumendu Roy, also a cinematographer for many of Ray’s films, mourns the delay in recognising Mitra’s contribution to Indian cinematography, which finally got him a long-overdue National Award for his work in Romesh Sharma’s New Delhi Times (1985), and the Eastman Kodak Lifetime Achievement Award for Excellence in Cinematography in 1992.

For Charulata, shot in confined studios on Bansi Chandragupta’s period sets, Mitra faced the possibility of multiple shadows created by the lighting required to shoot the interiors. After many experiments, Mitra got wooden boxes, approximately 3’x 2’ in size, fitted with 27 household lamps of 100 watts each in three rows, with separate switches for each row and a master switch for all the lights, a tissue paper covering the open side of the box. The whole box was then fitted into a usual 2KW light stand. It was fascinating to see the quality of sophisticated, shadowless light that came out of these crude wooden boxes. This kind of lighting replaced the earlier form of bounce lighting and turned into a trend among cinematographers in Bengal.

Filmmaker Goutam Ghose has a story to tell about Subrata Mitra the perfectionist. When Ghose was chairperson of SRFTI, Mitra was looking after the entire cinematography department as a member of the advisory board. “But he even got involved with the canteen. I found him monitoring each and every section - weighing the foodstuff bought from the market, judging its quality, how it was being cooked, whether it was being served right and so on. This told me about his deep involvement in whatever he took up - be it the Institute’s canteen, or playing the sitar, or painting, or cinematography. His sense of perfection and commitment remained the same.”

Though Mitra was born into a middle-class family, his father never stopped his son from chasing his dreams in photography and cinematography. When Renoir arrived in Kolkata to shoot The River (1950), Mitra, who was only 20 at the time, approached the director asking for work. Renoir turned him down, but when Mitra’s father requested the director to allow his son to be an observer during the shooting, Renoir could not say no. There was yet another young man present as an observer on the set, his name was Satyajit Ray.

During the last decade of his life, an angry Mitra carried on a one-man crusade to try and improve the quality of film projection in Kolkata’s theatres. He would personally go from one theatre to another to monitor the quality of screening, and even sat on a dharna in the Nandan complex as a protest against the inferior quality of projection. His point was that no matter how imaginative a cinematographer’s work is, and how brilliant the outcome, bad projection can kill good cinematography and subsequently, the film itself. The crusade died a silent death with his passing away. Cinematographer Adinath Das says he found Mitra sitting on the steps of Nandan one day with his head buried in his hands, in utter despair at the terrible projection quality.

Giving his ancestral home heritage status may perhaps keep him alive among film historians, film scholars and academics in the days to come instead of banishing him to obscurity.