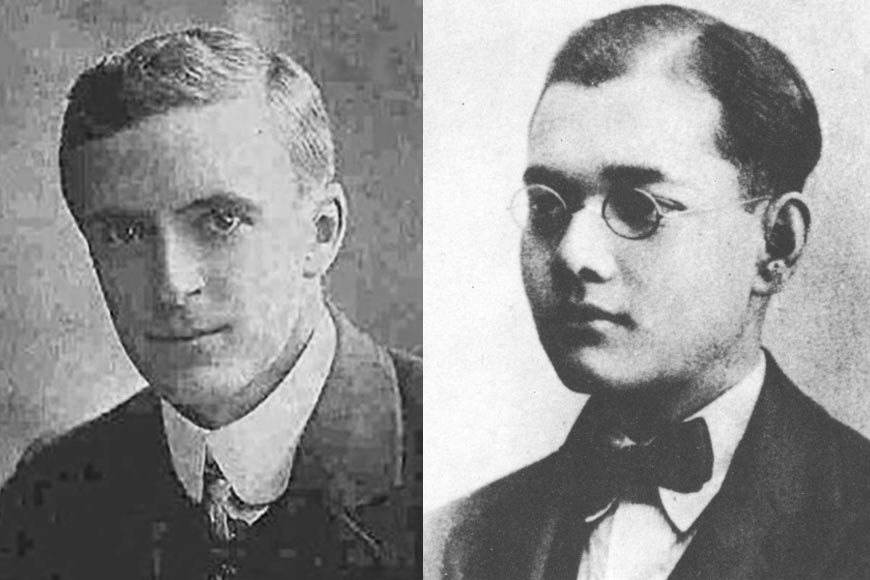

Subhas vs Prof Oaten, an encounter that changed two lives

In 2015, Norwegian filmmaker Erland Haugen was writing a screenplay featuring Prof Edward Farley Oaten. For assistance, he turned to local scholars and historians in the British city of Tunbridge Wells, Oaten’s hometown, wanting to know more about the man who has etched for himself a permanent place in the history of British India. Thanks to his encounter in 1916 with a 19-year-old student - Subhas Chandra Bose - on the steps of what was then Presidency College, Calcutta. In a most remarkable turnaround, it was for this student that Oaten was to write a heartfelt obituary, but more on that later.

Many historians have called it “a life-changing moment” between the teacher from Tunbridge Wells, and his pupil in India. Reportedly incensed by accounts of Oaten’s racist, high-handed behaviour toward his Indian students, Subhas and a few others physically assaulted the professor of history and allegedly threw him down the iconic main staircase of Presidency College, though this particular bit is probably not entirely accurate. To nobody’s surprise, however, Subhas was expelled and returned home to Cuttack.

However, as Sugata Bose writes in ‘His Majesty’s Opponent’, the Oaten episode turned out to be a defining moment in Subhas’s life, of which the young man himself was aware. In his autobiography three decades later, Subhas wrote, “Lying on the bunk in the train at night, I reviewed the events of the last few months.” And quoting him, Sugata Bose adds, “he realized that his expulsion from college had given him ‘a foretaste for leadership though in a very restricted sphere - and the martyrdom that it involves’.”

Needless to add, the incident has immortalised the name of Edward Farley Oaten, too. Though he had a distinguished career, it was his encounter with Subhas which has made him memorable in the history of the empire. Much like the filmmaker Haugen, however, many of us must have wondered what happened to the man at the receiving end of the assault. What happened to Oaten? Where did he go from there?

The answer is curious, to say the least. Born in Tunbridge Wells on October 24, 1884, Oaten was only 13 years older than his future student, which would have made him 32 at the time of the encounter. Academically gifted, the young Oaten studied history, and Greek and Roman literature in college, joining the Indian Educational Service and beginning his career at Presidency College. However, as he rose through the ranks of the service, going on to become Director of Public Instruction, Oaten developed a seemingly intense fascination both for Indian philosophy and the Bengali language. So much so, that he began taking Bengali lessons from economist, educationist and politician Pramathanath Bandyopadhyay, vice-chancellor of the University of Calcutta from 1946-49.

As a turnaround, there can be few to parallel this. From an arrogant, badly behaved, racist bully, Oaten now became so involved with India and Indians that he wrote multiple books that demonstrate his passion, among them ‘Anglo Indian History’, ‘Glimpses of India’s History’, and ‘European Travellers in India’. And when he returned to England after his retirement, he continued to correspond with Bandyopadhyay, writing letters to his former teacher in clear, fluent Bengali. Oaten died in his home town in 1973, and we still don’t know why and how his youthful, apparent hatred for all things Indian transformed into abiding love.

This would have ended matters, but for a small and very important addition. The man once hated by his students was also a poet of some note. As Haugen told a local newspaper in 2015, “Any leads from local historians to find any ancestors of Oaten or any other poetry by him would be much appreciated.” Well, the one bit of poetry that he, and we, have access to is an obituary written for the same student who had once assaulted him. The news of Subhas Bose’s alleged death in the Taihoku air crash of 1945 so moved the then 61-year-old Oaten that he wrote:

Did I once suffer, Subhas, at your hands?

Your patriot heart is stilled, I would forget!

Let me recall but this, that while as yet

The Majesty that you once challenged in your land

Was mighty; Icarus-like your courage planned

To mount the skies, and storm in battle set

The ramparts of High Heaven, to claim the debt

Of freedom owed, on plain and rude demand.

High Heaven yielded, but in dignity

Like Icarus, you sped towards the sea.

Your wings were melted from you by the sun,

The genial patriot fire, that brightly glowed

In India's mighty heart, and flamed and flowed

Forth from her Army’s thousand victories won!

The admiration for Subhas, the grief he felt at his former student’s passing, shines through every line of the poem. It is as though, more than 30 years after their encounter, Oaten was writing an apology as much as an obituary. Particularly touching is the comparison to the doomed Greek hero Icarus, who had devised a way to fly using wings made of wax, but they melted when he ignored warnings and flew too close to the sun, so that he fell into the sea and drowned.

Perhaps the comparison was Oaten’s way of telling the world that his student belonged to that category of people who can overcome the fear of death in their quest to fulfil their dreams, thereby becoming immortal. But it also shows the generosity of Oaten’s spirit, that he could grieve so openly for a man who had once so humiliated him.