Subhas and Emilie, what the world never knew

Subhas Chandra Bose and Emilie Schenkl in Karlsbad in 1935

For almost a year after his disappearance and alleged death on August 18, 1945, Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose’s family, not to mention the world at large, had no idea that he had left behind a wife and child in Europe. Even today, there are diehard believers of the theory that Netaji never married, let alone fathered a child.

In her book ‘The Bose Brothers and Indian Independence, An Insider’s Account’, author Madhuri Bose documents the circumstances under which Netaji’s wife Emilie Schenkl, an Austrian by birth who became a German subject, wrote to Netaji’s brother Sarat Chandra Bose in 1946, explaining how, owing to German laws which made it difficult for the country’s subjects to marry foreigners, she and Subhas had married in secret according to Hindu rituals, with only two friends knowing about it. And how they had decided to name their daughter ‘Amita Brigitte’, but changed it to ‘Anita Brigitte’, presumably to make it sound more German. In her letter, Emilie also made it quite clear that she was not seeking financial help, but merely informing the family of Anita’s existence, so that the child would be cared for should anything happen to her mother.

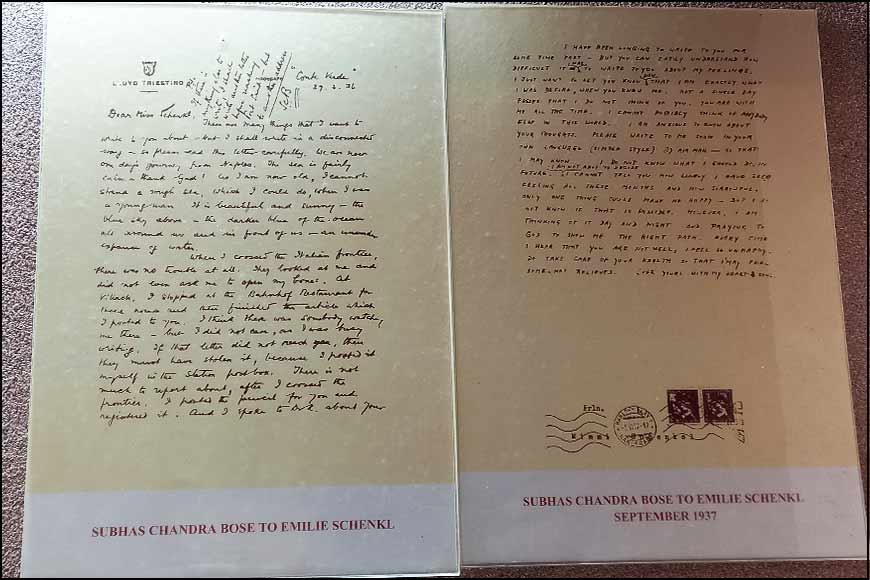

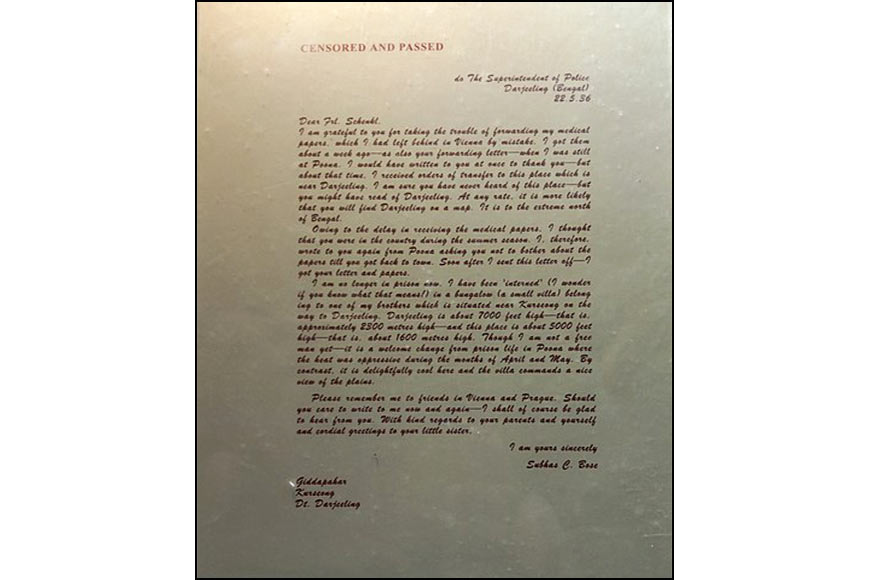

Letters to Emilie from Bose

Letters to Emilie from Bose

Despite his deeply held personal belief that his brother had not, as the British government suggested, died in an air crash in Chinese Taipei, Sarat Bose had no trouble accepting Emilie and Anita as his sister-in-law and niece. One crucial factor in this might have been a handwritten letter in Bengali that Netaji had left with Emilie, to be given to his family should anything untoward happen to him.

In fact, letters play an important role in establishing the relationship between Netaji and the woman who worked as his secretary while he wrote the book ‘The Indian Struggle’. In her letter to Sarat Bose, Emilie wrote, “Your brother has come to Europe again in 1941 and asked me if I could come and join him in Berlin to work with him. I agreed and joined him in April 1941 and we worked together till autumn 1942.

In fact, letters play an important role in establishing the relationship between Netaji and the woman who worked as his secretary while he wrote the book ‘The Indian Struggle’. In her letter to Sarat Bose, Emilie wrote, “Your brother has come to Europe again in 1941 and asked me if I could come and join him in Berlin to work with him. I agreed and joined him in April 1941 and we worked together till autumn 1942.

“Your brother asked me when I was in Berlin if I would accept his proposal to marry him. Knowing him since years as a man of good character and since there was a mutual understanding and we were very fond of each other, I agreed.”

How the two grew ‘fond of each other’ is fairly evident through their own correspondence. A very useful piece of evidence in this case is the book ‘Letters to Emilie Schenkl, 1934-1942’, edited by Netaji’s nephew Sisir Kumar Bose and grand-nephew Sugata Bose, first published in 1994. In the editors’ introduction, we find mention of A.C.N. Nambiar, a close associate of Netaji who describes him as “a one-idea man...singly for the independence of India”. However, he goes on to add, “I think the only departure, if one might use the word departure, was his love for Miss Schenkl, otherwise he was completely absorbed… He was deeply in love with her you see. In fact, it was an enormous, intense love for her that he had.”

Emilie and Anita in Vienna, November 1948

Emilie and Anita in Vienna, November 1948

The first letter in the book is dated November 30, 1934, and rather endearingly, Netaji describes the weather and scenery on his journey to Rome, and adds, “I may not be able to write to you till I reach India… I am always a bad correspondent - but not a bad man I hope.” And towards the end of the letter, he says, “I am sending this by airmail. Do not tell anyone that I have written to you by airmail, because I am not writing to anyone else by airmail - and they may feel sorry.” Clearly, he was prioritising his correspondence, and staying in touch with Emilie, who he was still addressing as ‘Miss Schenkl’, was most important.

Despite his apprehensions to the contrary, Netaji managed to write quite a few letters to Emilie before he reached India, including short notes from Venice, Athens and Cairo, detailing every step of his journey, much in the manner of one informing a member of one’s family. Back in India, writing from Woodburn Park, Kolkata on December 7, 1934, Netaji informs ‘Fraulein Schenkl’ of the death of his father Janakinath, and his mother’s extreme grief. Tellingly, he expresses his fear of ever being able to write to her again, owing to the British policy of ‘home internment’. “But in case I cannot, please do not misunderstand me. At present I am living like a prisoner in our house,” he writes.

Despite his apprehensions to the contrary, Netaji managed to write quite a few letters to Emilie before he reached India, including short notes from Venice, Athens and Cairo, detailing every step of his journey, much in the manner of one informing a member of one’s family.

In her book ‘Emilie and Subhas, A True Love Story’, Sisir Bose’s wife Krishna Bose wrote, “Of the friends and relatives who welcomed Anita sincerely, I would like to mention Basanti Devi, the widow of Deshbandhu Chittaranjan Das… Thakuma (Granny), as we called her, told me once that after Subhas was back in India from Europe in the latter half of the 1930s, she asked him, ‘You seem to like Vienna very much, is anyone special there?’ To her surprise, he blushed and attempted a feeble denial. Separately, Auntie Emilie told me on one of my visits to Vienna that Netaji had told her that Basanti Devi suspected he had a special person there.”

Subhash Chandra Bose to Emilie Schenkl

Subhash Chandra Bose to Emilie Schenkl

In yet another passage, Bose writes, “The next morning Auntie gave me a piece of folded paper and said, ‘This is for you, Krishna, something from me.’ Surprised, I looked at the rather worn-looking piece of paper and asked, ‘What is it?’ Auntie replied, ‘It is a love letter.’ It was, indeed, a beautiful love letter. I was deeply moved as I read it. It was undated but the envelope was postmarked 5th March 1936. Subhas had written to Emilie, ‘I do not know what the future has in store for me. Maybe I shall spend my life in prison, maybe I shall be shot or hanged.’ He went on, ‘Maybe I shall never see you again - maybe I shall not be able to write to you again when I am back - but believe me, you will always live in my heart, in my thoughts and in my dreams.’”

For all those interested, all the books mentioned in this article are still in print, or available online. The letters they contain bear testament to one of the best-kept secrets of Netaji’s personal life, one which he perhaps saw as a refuge when the outside world grew too oppressive, but one which he was able to enjoy only fleetingly before it was snatched from him. No matter how hotly we debate the existence of Netaji’s wife and daughter, the black and white letters tell their own story of love, longing, and devotion.