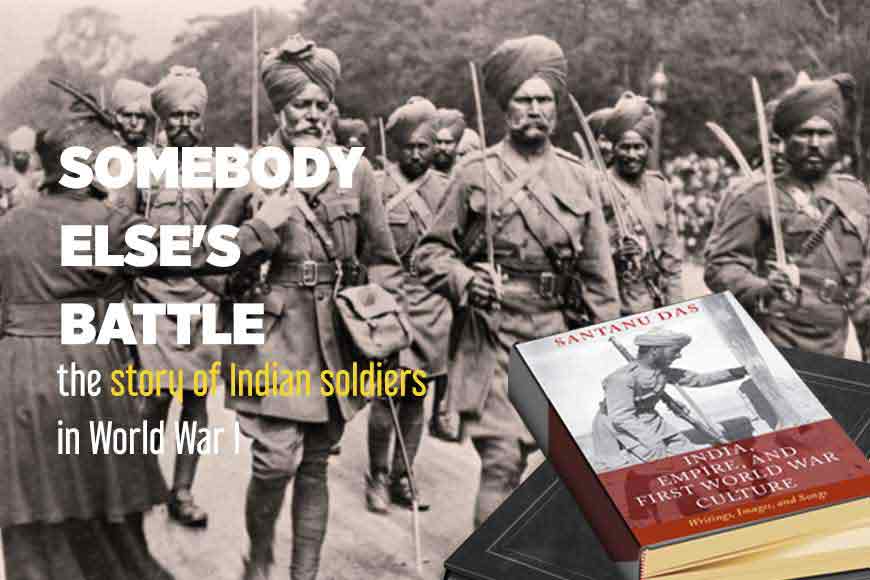

Somebody else’s war: Indian soldiers in World War I

Over one million serving, 62,000 dead and another 67,000 wounded, total dead at the end of the day: at least 74,187. These are the basic statistics about Indian soldiers during World War I (1914-1918). December 7 is traditionally celebrated as Armed Forces Flag Day in India. So today is as good a day as any to remember the thousands of forgotten Indian ‘sepoys’ who fought and died in what was essentially a European conflict, far from their native land, struggling to come to terms with alien cultures across the various theatres of war.

One Bengali scholar, educated at Presidency College and Cambridge University, has done more to focus the spotlight on those men than perhaps the entire body of war writing put together. His name is Dr Santanu Das, currently Senior Research Fellow at All Souls College, Oxford. His seminal 2018 book, ‘India, Empire and First World War Culture: Writings, Images, and Songs’ has recently become available in an Indian edition. As much for the serious researcher as the ordinary reader, the book will remain a landmark when it comes to Indian participation in the first ‘great’ war, a participation that both history and literature have largely ignored.

Not only is this aspect relevant, but also vital, since the Bengalis who participated in the war are also among the most comprehensive sources of information about it, thanks to their habit of writing down all they saw. “Unlike other Indian regiments, where the average sepoy came from the agrarian classes, Bengalis who joined the war effort were largely from the educated middle class.

Santanu’s near decade-long research took him from the “villages of Punjab to battlefields and POW camps and cemeteries – Ypres and Wunsdorf and Dar Es Salam – to museums across Australia and New Zealand”. Working with sources ranging from scraps of letters to photographs, audio recordings, news reports, long buried journals, songs, paintings, and anything else he could gather, Santanu amassed a wealth of information that had failed to make it to the public domain. The enormous scope and scale of his work would be impossible to cover in this single, brief article, but a particularly relevant aspect of it would be the extent of Bengal’s participation in the war.

Indian bicycle unit at Battle of the Somme.

Indian bicycle unit at Battle of the Somme.

Not only is this aspect relevant, but also vital, since the Bengalis who participated in the war are also among the most comprehensive sources of information about it, thanks to their habit of writing down all they saw. “Unlike other Indian regiments, where the average sepoy came from the agrarian classes, Bengalis who joined the war effort were largely from the educated middle class. Many of them joined from England itself, and occupied plum positions within the army, such as ace fighter pilot Indra Lal Roy, but even those who signed up in Calcutta were qualified professionals, different from the average sepoy. Which is why the volume of testimonies from them is disproportionately high, compared to their actual numbers,” says Santanu.

Initially kept out of the war by the British for their supposed “effeminate and non-martial” character, the Bengali community, led by a section of the aristocracy and other prominent citizens, launched a strenuous propaganda effort to be counted among the ranks, “as a form of racial justice and equalization”, says Santanu. A determination to get rid of the ‘coward’ tag.

One of the most famous names to sign up was Kazi Nazrul Islam, who never actually saw action, but whose literary interpretations of the war were both powerful and poignant. For purposes of documentation, however, far more important are three other Bengali men, whose accounts form an entire chapter in Santanu’s book – Ashutosh Roy, Sisir Prasad Sarbadhikari and Kalyan Mukherji. Sarbadhikari’s uncle, a doctor, was one of the founding members of the Bengal Ambulance Corps (BAC), which provided stellar service particularly in the Mesopotamian battlefields.

Indian soldiers in action on the famed Western Front

Indian soldiers in action on the famed Western Front

In August 1924, a monument was built in Kolkata in memory of the first Bengali Regiment (initially raised as a double company distinct from the BAC), to honour the 56 soldiers who lost their lives in World War I. Among them was Kalyan Mukherjee, whose letters to his family, primarily to his mother, spoke of the horror and degradation of war, and became the basis for an extraordinary memoir by his 85-year-old grandmother Mokkhoda Devi, titled ‘Pradeep-Kalyan’.

In a bizarrely tragic twist, Mukherjee, his young daughter, and his mother died within months of each other, leaving the grieving Mokkhoda to immortalise her grandson through her work. Santanu writes of him as a prisoner of war, “Being an officer, he was treated relatively well after the surrender and was allowed to write home at least once a month. His are so far the only Indian letters we have from among the 10,000 Indians besieged at Kut (Kut-al-Amara).”

One of the most famous names to sign up was Kazi Nazrul Islam, who never actually saw action, but whose literary interpretations of the war were both powerful and poignant.

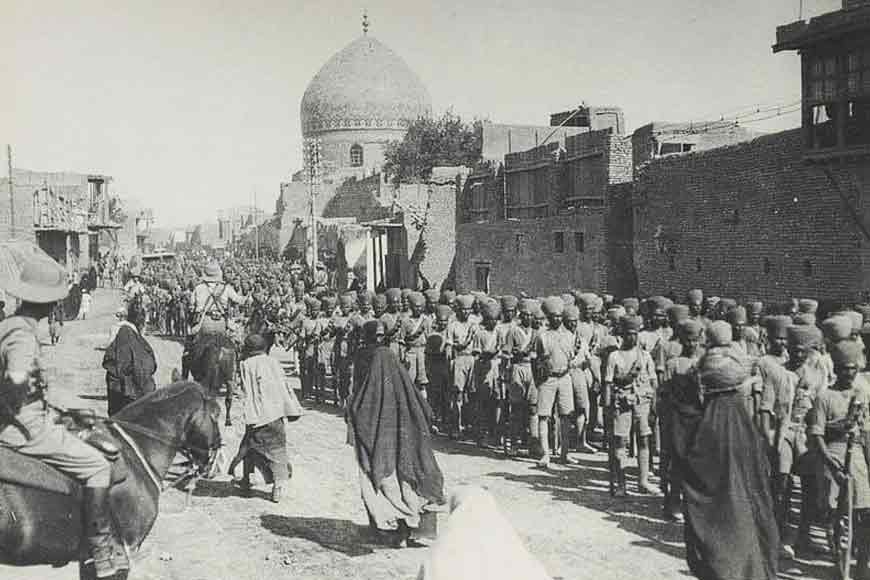

Sarbadhikari had just completed a degree in law when war was declared. He was among the citizen volunteers recruited as privates in the BAC for Mesopotamia. His motivation, a ‘spirit of adventure’. “The Corps…. reached Amara on 15 July and set up the Bengal Stationary Hospital in Amara where they were stationed for the first two and half months. In September, some thirty-six of them, including Sarbadhikari, were chosen to be sent to the firing line as part of the 12th Field Ambulance of the 16th Brigade. The story centres around this group of idealistic Bengali youths as they encounter the battle of Ctesiphon (November 1915), the resultant siege of Kut (December 1915-29 April 1916) and captivity for the next two years. As a medical orderly who knew English and picked up Turkish, Sarbadhikari was made to work in hospitals in Ras-el-Ain and Aleppo, and then in the German camp at Nisibin. The memoir is closely based on his wartime diary, which has its own tale of trauma and survival to tell…” writes Santanu.

Indian troops march into Baghdad

Indian troops march into Baghdad

Sarbadhikari’s book, titled ‘Abhi Le Baghdad’, is such a remarkable document that it merits an article by itself. As a prisoner of war, he wrote down his experiences in a diary, whose pages he would tear off and hide in his boots to avoid detection. That diary came back with him to Calcutta, where it remained until his daughter-in-law Romola Sarbadhikari, who herself passed away recently, persuaded him to publish it as a book, which she wrote based on Sarbadhikari’s retellings. For five years from 2006, Santanu conducted a series of interviews with Romola to learn more about her extraordinary father-in-law, and it is almost entirely owing to his efforts that the book has been rescued from obscurity.

While both Mukherjee and Sarbadhikari describe both the horror and the futility of war, the sense of immediacy and the vividness of their writings, and their ability to take a dispassionate point of view, make them invaluable simply as sources of information. “Mukherjee’s letters are amazing,” says Santanu. “Like Tagore, he was both anti-colonial and anti-nationalist, against violent forms of protest, and comes across as a true intellectual.”

But the grimness is interspersed with moments of comic relief. “On reaching Basra, Dr Kalyan Mukerjee wrote to his mother thus: ‘Ahre Ram, is this the Basra of Khalif Haroun al-Rashid? Chi! Chi! There is not even the faintest sign of roses; instead what we have here is a 10-12-hand long 5-6-hand wide and 20-21-hand deep ditch. Into it flows the water of the Tigris, knee-deep or waist-deep. Each of these ditches is home to at least two hundred thousand frogs - small, big and medium-sized. Most of them are bullfrogs. What a terrible din they make’,” writes Santanu.

37th Indian Brigade in Basra

37th Indian Brigade in Basra

Or sample this about Sarbadhikari’s colleague Prafulla Chandra Sen who “distinguishes, in his reminiscence, between the different sounds on the battlefield: the ‘miao’ sound of the .303 British bullets, the ‘bee-like buzzing’ (‘bhramarer gunjan’) of the bullets fired by the Arab soldiers and the ‘hiss’ of shells”.

To go through these and other reminiscences is almost like reliving the years of terrible conflict. It is to Santanu’s immense credit that we finally have a complete picture of the culture that emerged from that conflict, a culture that has shaped all subsequent generations.