Slavery, the dark secret from Calcutta’s past

East India House in London in 1800

Slavery. An ugly word to describe an ugly, despicable practise. Owing to what history has documented, most of us probably tend to equate the term ‘slave’ with the image of Africans working on huge American cotton plantations, and the ‘slave trade’ between the American continent and several African nations. What many of us forget, however, is that slavery is an ancient cultural institution which thrived across the world in one form or another for centuries, and in some cases, continues to do so.

What even fewer among us will probably know is that our own city’s European past hides a dark secret that not many chroniclers have written or spoken about. And that is Calcutta’s position as a flourishing outpost of the slave trade in the 18th century, with more than one market in the city dealing in the business of buying and selling humans, until the British East India Company finally outlawed it in 1843 with the passing of the Indian Slavery Act. Much earlier, in 1789, the ‘Company bahadur’ had issued a proclamation (not an official government act) declaring that slavery was illegal, though the Compnay itself had been a partner in the immensely profitable trade until 1764.

Whatever the proclamation, however, it was considered quite fashionable among the wealthy Europeans of Calcutta to own multiple slaves in the 18th century. The slave trade in this part of the country was largely the domain of the Portuguese and Mawg (Burmese) pirates, with the English and Dutch picking up the occasional scraps. After 1770, with the Great Bengal Famine raging across the province, impoverished natives were voluntarily selling their children into the trade, and even the occasional Eurasian or European were to be found offering their services as slaves, in order to escape abject poverty. One other steady source of slaves were the various ships attacked by the pirates, with their crew taken prisoner and sold into slavery.

Calcutta High Court in the 1890s

Calcutta High Court in the 1890s

By 1770, as we were saying, the practise of keeping slaves had become so well entrenched that even the courts recognised a person’s right to absolutely own another person, and handed out harsh punishments to runaway slaves. Dr H.E. Busteed, that renowned chronicler of old Calcutta, quoted Calcutta Police chargesheets from 1778 to show three cases of runaway slave girls, whose ethnicity is not mentioned. One of the girls, referred to only as ‘Peggy’, was sentenced to five strokes of the cane, while another called ‘Sarah’, being a repeat offender, was given 15 strokes. Needless to add, the girls were returned to their ‘owner’. Also from police records comes the case of one Mr Levitt, who produced one of his slave girls named ‘Polly’ as witness to a robbery.

As the 18th century came to a close, popular sentiment began gradually to turn against the barbaric custom. One contemporary publication printed a scathing editorial about the “barbarous and wanton acts of more than savage cruelty exercised on the slaves of both sexes by that mongrel race called the Native Portuguese”. It is unclear whether the custom would have been any more acceptable had it been practised by any race other than the plainly despised Portuguese.

Abolition was not an immediate goal, however. Numerous advertisements in old copies of the Calcutta Gazette (1784-1818) frequently requested information about runaway slaves, sometimes ‘branded’ ones. On December 2, 1784 for instance, one Lieutenant Valentine Dubois advertised for two slave boys who had run away from his household, having allegedly stolen some crockery and cutlery. The boys were called Sam and Tom, and had both attained the ripe old age of eleven. These hardened criminals had been branded with the initials ‘V.D.’ on the right arm, above the elbow, which would have made identification easier, and placed their ownership beyond dispute. Dubois offered a reward of Rs 100 for their return.

The same year, the edition dated June 17 had details of a runaway Malay slave named ‘Wilks’, with a request that “gentlemen should detain him” should he offer his services to them. Again on November 16, 1786, an advertisement gave an account of two ‘drummer boys’ bearing the last name De Rozario, who had run away from Fort St George in Madras and may have made their way to Calcutta.

Then again in December 1785, we come across the description of two Malay slave boys who ran away from the employ of Rev. Mr Blanchard, apparently with stolen jewellery and money to the tune of several thousand rupees. What the reverend was doing with so much money and jewellery is not made clear.

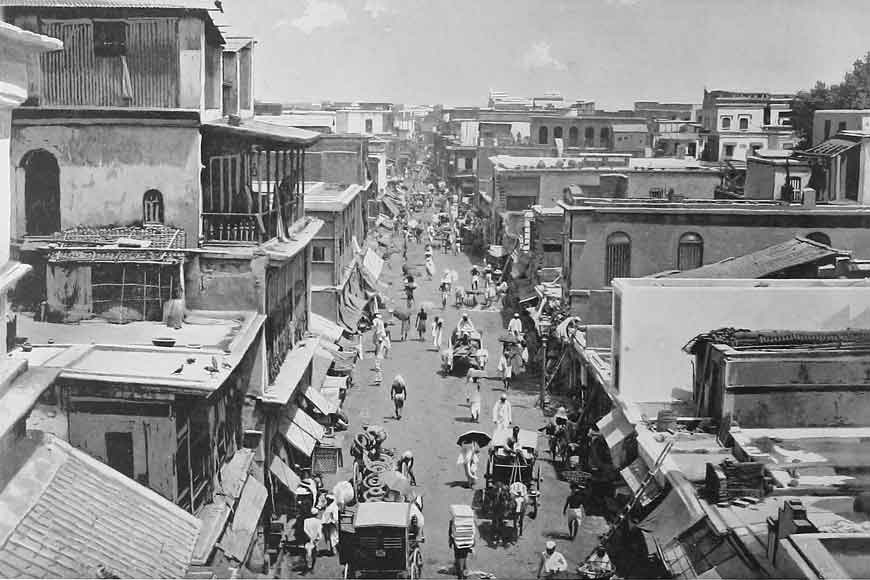

An old, undated photo of a Calcutta bazar

An old, undated photo of a Calcutta bazar

Advertisements were also put out for the purchase and sale of slaves, with their accomplishments and abilities listed in some detail. Chief among these appear to have been their musical and culinary skills. It is clear from these public notices that most slaves in 18th-century Calcutta were either of Malaysian or ‘Coffree’ origin, the latter being a distortion of the Persian word ‘kafri’, commonly used to indicate African descent.

Before slavery became a lucrative trade in Bengal, the Portuguese would capture people from Asia’s southeastern coast and sell them off to the Dutch. The East India Chronicle for 1758 provides a detailed account of the horrific cruelties to which captives from the southern regions of Bengal were subjected, and such was the fear of the Portuguese menace that attempts were made to keep them away from Calcutta by laying a chain across the river Hooghly near Garden Reach.

As the trade began to become more profitable in Bengal, however, the once feared pirates became favoured trading partners. And the reason was, as always, money. Sample this advertisement from 1781: “To be sold, a fine coffree boy, that understands the business of butler, and etc. Price four hundred sicca rupees. Gentlemen may see him by applying to the printer.” Rs 400 was a very large amount of money in contemporary terms. The kind of money that humans would sell their souls for, forget selling other humans.

Finally, it is worth noting that the Slavery Abolition Act had been passed in the British Parliament in 1833, making the purchase and ownership of slaves illegal throughout the British Empire – except for the territories governed by the East India Company, which had relentlessly protested that the custom that existed in its territories in South Asia was ‘Free Labour’ and not slavery. We leave you to work out the difference.