Shyamali Khastagir, The woman behind Santiniketan’s Shonibarer Haat—GetBengal story

In a world so often entrenched in violence and discord, there exist a few individuals who illuminate lives with their righteous spirit, driven not by selfish motives but by a genuine desire to make the world a better place. Among these luminaries was Shyamali Khastagir of Santiniketan—a multifaceted personality, encompassing roles of artist, sculptor, author, explorer, and above all, activist.

Khastagir's journey was shaped by her early exposure to nature and artistry. Born in Kolkata in 1940 to renowned artists Sudhir Khastagir and Manorama Debi, she was raised in the midst of creativity and cultural richness. However, tragedy struck early in her life with the untimely demise of her mother when she was just ten months old. Raised in the nurturing embrace of her father's workplace at Doon School and her aunt's residence in Sylhet, she found solace and inspiration in the lap of nature.

In 1949, when Shyamali Khastagir was around 10 years old, her introduction to Santiniketan marked the beginning of a profound connection with the environment. She first came to Santiniketan with her paternal grandmother, Sauranalini Debi, and they stayed in Meera Devi’s house in Malancha. Meera Devi was the daughter of the great bard Rabindranath Tagore. Around 1950, Shyamali was admitted to the Ashramik School of Santiniketan, which was started by Tagore himself. Her formative years in this ‘open-air’ school, along with her later education in Kala Bhavan, not only brought Shyamali in contact with some of the stalwarts of that era and classmates who would later become famous in their own right, but also nurtured her love for nature. This environment played a crucial role in shaping her worldview and instilling in her a deep appreciation for nature's beauty. The seeds of conservation were sown during that time, and throughout her life, she cherished these memories, recognizing the importance of conserving the environment.

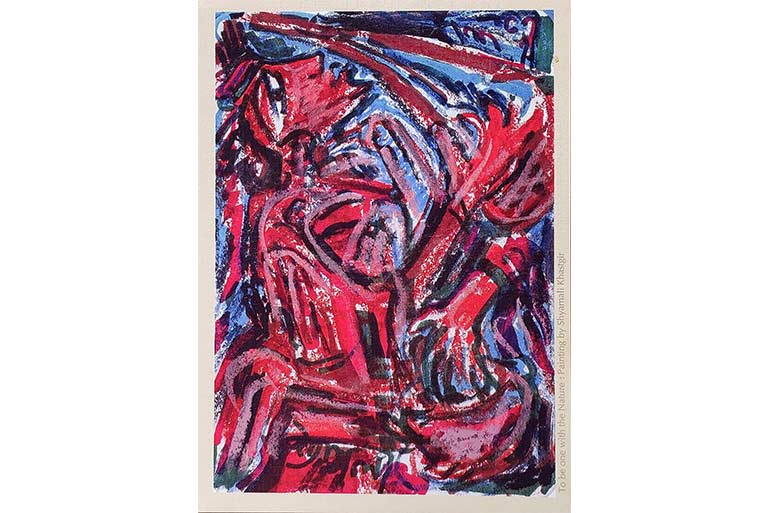

As an artist and the daughter of a renowned artist, Shyamali Khastagir was immersed in the world of art from a very young age. At the age of 10, she showcased her artistic talents at her father's exhibition in Allahabad, where several of her paintings were displayed alongside his work. As she matured, Khastagir used her art as a form of protest, expressing her dissent against the consumerist society. One of her notable creations was the Vasundhara Dolls, which served as a symbolic protest against the rampant consumerism of the time. These dolls carried a powerful message about the need for sustainable living and environmental consciousness.

Khastagir was also instrumental in starting the famous ‘Shonibarer Haat’ (Saturday Market) in Santiniketan, along with her friends. However, she became disillusioned over the years as the original ethos of the market was lost, giving way to a more commercialised model. She became a vocal critic of this modernised version of the ‘Shonibarer Haat,’ advocating for a return to its roots and the preservation of its original spirit.

In 1962, Khastagir's marriage to Tan Li, an IIT professor of Chinese descent, stirred controversy amidst the backdrop of Indo-China tensions. Their subsequent relocation to Canada exposed her to the perils of unchecked consumerism and the darker facets of modern civilization. Disillusioned by the rampant materialism, she yearned for the simplicity and harmony of her upbringing in Santiniketan. In her own words it was like ‘Living in a House of Credit Cards’.

The turning point in Khastagir's life came with India's nuclear tests in 1974, which galvanised her into action against nuclear warfare. Her activism extended beyond borders, as she joined anti-war movements in Canada and collaborated with organisations advocating for peace and nuclear disarmament. In this context Shyamali writes: “When in 1974 India tested the first nuclear bomb, I woke up and I started reading several texts. I was trying to understand the inhuman angle of nuclear weapons, why this nuclear war, why are so many nations spending so much money on nuclear weapons. The experience of Latin America also created an interest. While in Canada I started attending different anti-warfare meetings and protest marches against nuclear missiles, this largely opened my eyes about the ill effects of nuclear warfare. I spoke to those who spread the message of peace against war, and learnt of their horrific experiences during war.”

Khastagir was also active in various anti-war organisations in Canada, including the 'Voice of Women' and the 'Canadian Coalition for Nuclear Responsibility.'

In 1981, Khastagir permanently returned to India, settling in her Santiniketan home, Palash Bari. Despite her Santiniketan roots, she travelled extensively across India. During one of her trips, she met Gandhian leader Pannalal Dasgupta, who later lived with her in Santiniketan. Together, they worked to revive Bengal's rural economy, organising festivals like the Meen Mangal Utsav and creating self-help groups and cooperatives. They established the Chhoto Shimulia farm, employing local organic technology to promote sustainable agriculture.

Khastagir also joined the organisation Anumukti upon her return to India. In 2000, she collaborated with physicists Suren Gadekar and Sanghamitra Gadekar in Jharkhand, where uranium mines were causing dangerous levels of radiation. She worked tirelessly among the local villagers, using slides and projectors to raise awareness about the health risks associated with radiation exposure, such as cancer and birth defects.

Shyamali Khastagir passed away on August 15, 2011, in Santiniketan. As per her last wish, the last rites were performed putting her to rest close to the earth she loved and believed in. In her book, 'In the Middle of Explosion,' she dedicated her work to India's rural folk and children, envisioning a world free from war, strife, and violence, where people could live in harmony with nature. Whether this vision will ever come to fruition remains an open question.