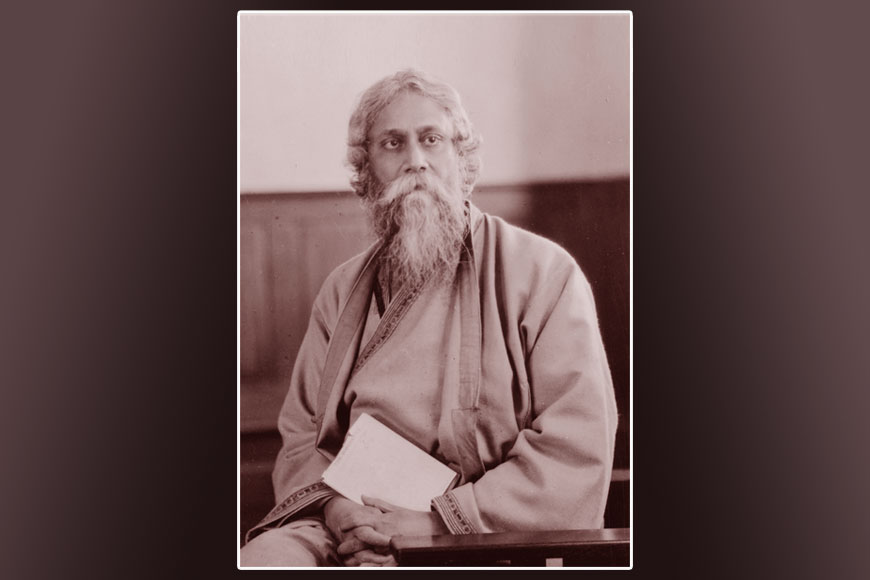

Satyaprasad Gangopadhyay -- Rabindranath Tagore’s first publisher

At times photographs can start a lifetime bond! It was the year of 1914, when Rabindranath Tagore went to Allahabad and stayed for about three weeks with Pyarilal Bandyopadhyay, the son-in-law of his nephew, Satyaprasad Gangopadhyay. During his stay there, he spotted a photograph hanging on the wall of the house. The time-worn image was that of Satyaprasad Gangopadhyay. Suddenly his creativity was stoked by the memory of his beloved friend/nephew and he penned the poem deviating from the style he was writing during the period.

The identity of the person in the photograph who inspired Tagore to write the poem has been at the centre of a dispute for years. Moitreyee Devi in her book, ‘Swarger Kachhakachhi’ wrote: “... I remember when he was explaining the poem ‘Chhobi’ to a little girl. He was telling – ‘Once I had found a picture while staying at Allahabad with Satya – I wondered – the person, who had existed like truth a couple of days ago, occupying a considerable amount of space in our life, can now only be found long distance away. Our life continues with the same pace – while that of the person had come to a grinding halt. Memories too fade out – yet – did I forget you? Do we always need to be conscious about our eyes – that we have eyes? Although it is the eye that enables us to behold. Similarly, I do not remember you often, but you had once strongly existed within the core of my life. And that is the reason for which my life has been so blissful and elegant. ...”

Tagore introduced his readers to his world through his autobiography, ‘Jeebonsmriti’. He poignantly writes about his childhood and about his two close friends/companions who grew up together in the ‘Andarmahal’ of Jorasanko under the strict vigilance of a flock of maids and servants and private tutors. His elder brother Somendranath and their nephew, Satyaprasad Gangopadhayay were thick as thieves although both Somendranath and Satyaprasad were at least two years senior to Rabindranath. In his memoir the poet writes humorously, one day he noticed his companions left him in the lurch and smartly boarded the family conveyance and left for school, little Robi was disconsolate. He cried and created a ruckus. At that point, one of his home tutors came and slapped him tight and said, “Now you are crying to go to school but a day will come when you will cry to avoid going to school.”

Satyaprasad was the son of Maharshi Devendranath Tagore’s eldest daughter, Soudamini Devi. Satyaprasad was a sincere student and brilliant in academics. The poet writes, “Satya was the best among us in studies.” He often received prizes from his school for his outstanding results and Rabindranath proudly displayed them to his cousin Gunendranath (Maharshi Debendranath’s brother Girindranath’s youngest son) and announced cheerfully how Satya had made them all proud with his excellent track record in academics.

Rabindranath’s thread ceremony was performed along with Satyaprasad and Somendranath. The boys were growing up together. In 1881, when Rabindranath was 21 years old, Maharshi Devendranath decided to send both Rabindranath and Satyendranath to England. The duo left on Kaizar-e-Hind ship that sailed from Calcutta port on April 11. But when the ship reached Madras, Satya insisted Rabi to return home to Calcutta. The poet writes, “Satyaprasad pretended he was very sick and had blood dysentery and I believed him…. I returned with him. I was annoyed with Satya’s attitude but chose to remain silent.” Their return was not welcomed by the seniors in the family but Debendranath seemed okay with the idea and did not seem to mind.

Satyendranath had inherited the genes of the Tagore family from his mother’s side and growing up in the enlightened house of the Tagore family gave him ample scope to hone his creativity. In the month of April 1885 Balak magazine was launched under the editorship of Jnandanandini Devi, wife of Rabindranath’s elder brother Satyendranath Tagore. This was an in-house magazine for children and teenagers priced at Rs 2 for each edition. There were 13 articles in the inaugural issue with Rabindranath contributing five of them. Satyaprasad had inherited a natural flair for writing and he penned an amazing travelogue for the first issue titled, ‘Darjeeling-Jatra.’ The author painted a surrealistic picture of the hill station with words. His vivid and poetic descriptions infused life to mundane sights and sounds to the ‘Queen of Hills.’

In 1896, a graphical advertisement was published in the ‘Kartik’ (October-November) edition of ‘Tattvabodhini’ magazine. The commercial announced, ‘Poetry books of Rabindranath Tagore/ including handwritten photographs of the poems have been published. Twenty poems have been printed in it .... These books are being published in three types – cheap and affordable edition, ordinary and premium editions.’ At the end of the advertisement, it is written, ‘The books are available with me, Satyaprasad Gangopadhyay, No. 6 Dwarkanath Tagore's Lane, Jorasanko Calcutta.’

It is evident from the bulletin that Rabindranath’s first book of verses was published by his nephew, Satyendranath. In fact, the poet acknowledged his debt to his nephew in the preface and wrote, “All my books of poetry were published together. I am grateful to my beloved publisher for this.” Satyaprasad had printed 1,000 copies of this 476-page book of verses. But 10 years prior to that, in 1886, Satyaprasad had printed 1,000 copies of Rabindranath's 242-page novel, 'Rajarshi' at his own expense.

Satyaprasad was not only an indispensable member of the family but was also the most trusted, reliable and efficient manager of the Jorasanko Tagore family’s in-house creative pursuits like the Grahasthya Natyasamiti (amateur theatre group) or ‘Khamkheyali Sabha.’ His suggestions, ideas, writing etc were also crucial for the publication of magazines like ‘Sadhana’ and ‘Tattvabodhini.’ With advancing age, Maharshi Devendranath relied immensely on his grandson. In fact, in July 1896,he was officially appointed manager (Seresta) of the sprawling Tagore estate with a monthly salary of Rs 200. He was given the responsibility to scrutinize all official documents pertaining to the zamindari and only after he stamped ‘Examined’ on the documents, Rabindranath would release the papers with his signature without even glancing at the contents for once.

Maharshi's last will or testament was signed in the presence of solicitors Mohini Mohan Chatterjee, Priyanath Shastri and Satyaprasad. This created quite a stir within the family and the blame game began. Words of discontent did not remain concealed any more. Rabindranath had already started distancing himself from mundane monetary matters and was busy setting up his dream project at Santiniketan. Satyaprasad was living on the ground floor of the Jorasanko mansion with his widowed mother, Saudamini Devi and his own family. He no longer enjoyed his work and wanted to resign from his post. When Rabindranath heard this, he dashed him a letter on 17 April 1902, saying, ‘I am really saddened to receive your letter. I can very well understand the fatigue and humiliation you have been facing ever since shouldering all financial responsibilities and I can also feel your yearning to leave all money matters behind and relax and get a whiff of fresh air…” He also adds, “But if you retire, the entire work will come to an abrupt halt. I shall have to take up the burden and I am no more capable of doing all the running about now.”

Maharshi died in 1905 and his death tolled a change of guard in the Jorasanko Tagore house. Both Satyendranath and Jyotirindranath had relocated to Ranchi long before Maharshi’s demise. The entire family of the poet’s elder brother, Dwijendranath had moved to Santiniketan and lived there. Rabindranath moved to and from Jorasanko but did not stay there permanently. Hemendranath’s sons continued to stay at Jorasanko but were not involved in the upkeep of the mansion. As a result, Satyaprasad had to continue work as the manager. In 1909, Satyaprasad once again communicated with Rabindranath and requested the poet to release him from his duties. Rabindranath was deeply hurt but this time he let him go. He bade goodbye with an emotional letter where he spoke of the years of bond they both shared with the house, with each other and that his presence in the house made Jorasanko feel like home for the poet.

(Source: Jibonsmriti by Rabindranath Tagore; Letters of Tagore; Swarger Kachhakachhi by Maitreyi Devi)