Satyajit Ray, the man who brought out the best of Bengal’s rural life on screen

Existing in the world without having seen the sun and the moon

That’s what legendary world-renowned film maker Akira Kurosawa had once said after watching the movie Pather Panchali and while discussing the film-making style of another legend, born and brought up in Bengal, Satyajit Ray. Pather Panchali was indeed a timeless classic and the manner in which, Ray gave his own touches to Apu Trilogy (all three novels written by Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay) had elevated the movies to a platform never touched before. From the depths of emotions subtly expressed to the heights of background scores, singers, actors, musicians, handpicked by Ray after a lot of experimentation, Ray was a class by himself. No wonder even Kurosawa was touched by his genuine creativity.

A scene from Pather Panchali

A scene from Pather Panchali

Ray was fascinated by the world of Bengal’s rural life. Having spent a sizeable portion of his life in Santiniketan, Satyajit Ray was close to nature and rural life, their style, their dialects. Not just Apu Trilogy, in movies like Ashani Sanket, a film set in a village during World War II and the Great Famine of 1943, through the eyes of a young Brahmin doctor-teacher, Gangacharan, and his wife, Anaga, Ray again brings out rural dialogues, underlying wishes and their world of innocence as well as deceit. The human scale of a cataclysmic event that killed more than 3 million people and the breakdown of traditional village norms under the pressure of hunger and starvation, somewhere struck a chord with the human tale of love and loss that Ray usually portrayed on celluloid.

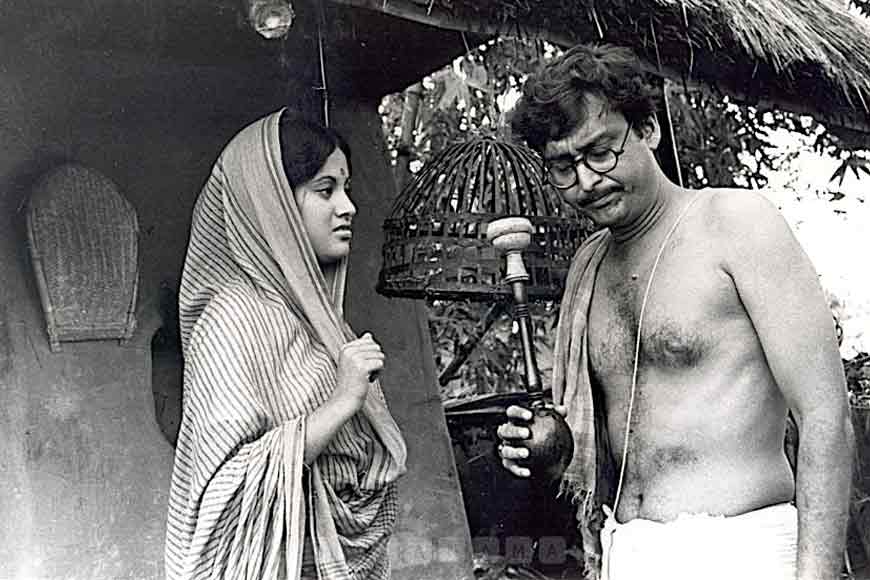

A scene from Ashani Sanket

A scene from Ashani Sanket

While, Pather Panchali was the first film of what came to be known as the Apu Trilogy - the second was Aparajito, in 1956, and the third, Apur Sansar, in 1959. All three were masterpieces, closely weaving hopes and despair of the common man, through protagonist Apu. There is a kind of musical cohesion in the trilogy that Ray made, bringing Apu and other characters to life. In an article Ray once wrote: “I chose Pather Panchali for the qualities that made it a great book: its humanism, its lyricism, and its ring of truth.” Ray kept focusing his adaptation on the poverty and simple living of a family in rural Bengal, just like the original novel does. Bibhutibhushan had a breath-taking narrative style, where he touched upon the details of every corner of rural Bengal along with the minute emotions that each of us suffer from, be it in death or birth. Ray could build up that atmosphere with his midas touch, from the subtle difference between dawn and dusk, to the stillness that precedes the first monsoon shower.

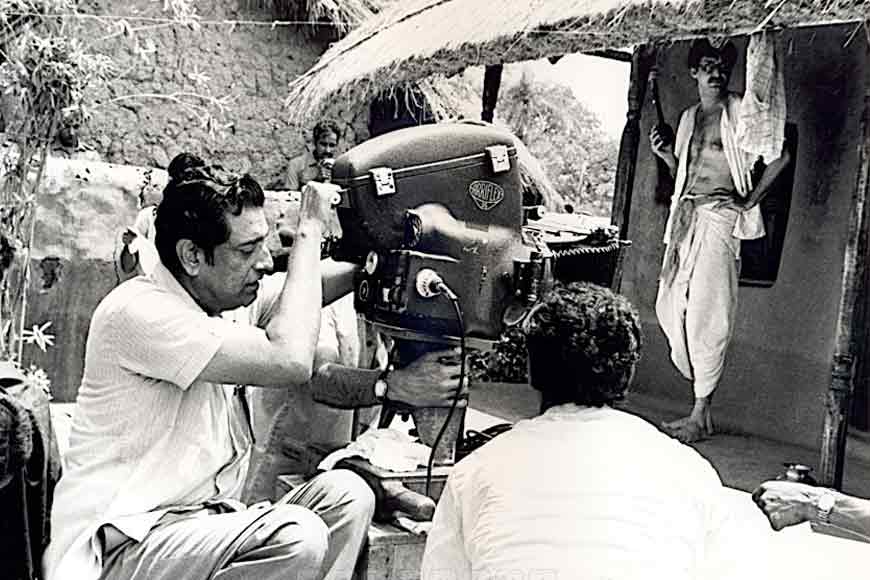

Shooting of Ashani Sanket

Shooting of Ashani Sanket

Every detail of a rural life opens up behind Ray’s camera. They are put to life in scenes where the children follow the village sweet-seller with a dog trailing them and the procession reflected in a pond; Apu throwing a stolen necklace in the pond to save his sister’s secret, Apu and Durga racing through a field of kaash flowers for their first glimpse of a train or Sarbojaya’s outburst after Harihar comes home and learns of Durga’s death. They are all scenes with a contrast, of joy and anguish, of despair and love of simple rural folk. Similar emotions are reflected in another timeless adaptation of Tagore’s Postmaster. Ratan, the simple village girl and her undying attachment to the postmaster who comes to the village.

A scene from Pather Panchali

A scene from Pather Panchali

In words of Kurosawa: “Pather Panchali is the kind of cinema that flows with the serenity and nobility of a big river. People are born, live out their lives, and then accept their deaths. Without the least effort and without any sudden jerks, Ray paints this picture, but its effect on the audience is to stir up deep passions.” True, Satyajit Ray could indeed bring out Bengal’s rural life at its best on celluloid and touch the hearts and souls of the audience. On his death anniversary, it is proved again, some creative minds never die. Satyajit Ray was one such master director.