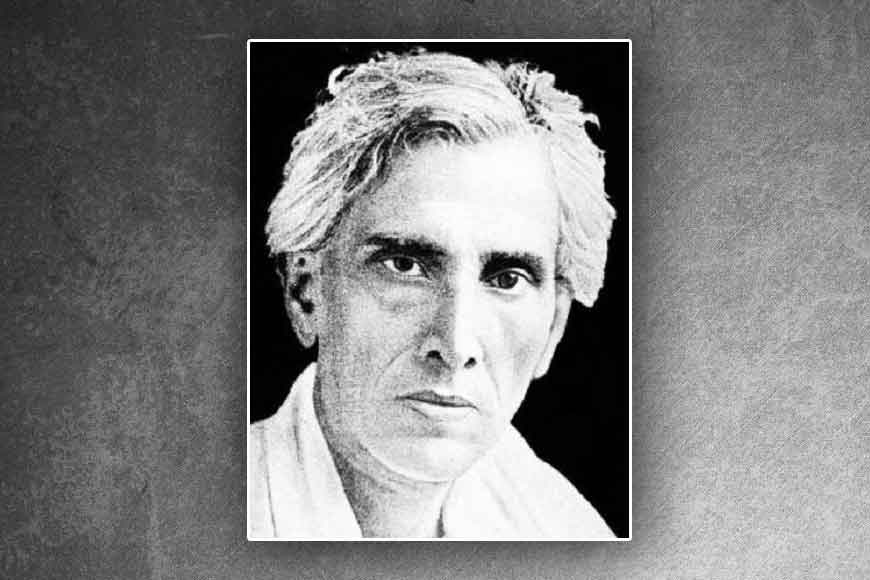

Sarat Chandra, the creator of iconic women characters in Bengali Literature – GetBengal story

At times one wonders, if Sarat babu overdid the cause of women in the Indian society as Rabindranath mentions in Shadharon Meye. But then in the modern context, one realises how relevant this novelist was, in highlighting women’s cause at every step, in every novel. His women are bold, brave and fierce in their own small world.

Sarat Chandra wrote his last complete novel Shesh Proshno, that was translated by members of the English department of Jadavpur University to take the book to an international audience. The novel opens with a group of tourists enjoying the splendor of Taj Mahal. Among them is Ashu Babu, who cannot stop extolling its beauty, the very greatness of the love which led to its creation. Everyone is in broad agreement with him, except Kamal, the low-caste wife of Shibnath, an unscrupulous businessman. Kamal surprises everyone by quietly denouncing the Taj Mahal as a monument which was a result of an emperor’s ego, rather than his unflinching love.

Her statement is met with disbelief and disapproval. It was a time when young women kept their opinions to themselves and a woman who chose to air such unconventional, rebellious opinions stood a chance to draw condemnation and criticism. But Kamal rebels repeatedly and her daring and very progressive opinions shock everyone.

As a novelist, short story writer and essayist, Chattopadhyay was concerned about the subjugated status of Indian women. His was a time, that saw emergence of several reform movements like women’s remarriage, education and freedom -- movements spearheaded by the urban elite class of Calcutta". Yet Chattopadhyay knew in villages, things were in utter contrast. Lives spent within the joint family were constrained by obscurantism that was medieval. His female protagonists repeatedly come as Madhabi in Bardidi, Rama, the child widow who suffers in Palli Samaj and even Parbati of Debdas.

Most of his later works including The Final Question written in 1931, not only voice the social protest of the Hindu wife or widow, but question anew the very relationship between woman and man. It is through the persona of Kamal, he tried to answer what is love, marriage, relationship of a man and woman, and degree of freedom and emancipation.

Kamal does not care when her ‘husband’ abandons her, she freely declares they were not married in the proper way; she works in close contact with the tannery workers when an epidemic of influenza breaks out in Agra; she is drawn to help a young revolutionary called Rajen when most of his associates shun him; she dares Harendra to spend the night at her home for he is after all a Brahmacharya, and then she chooses to make a new life with Ajit Babu but refuses to marry him.

Does the character of Kamal ring a bell? Isn’t she more bold, than even the 21st century urban Indian woman who bears the flags of feminism? The woman loses herself in the many demands of the society, but Sarat Chandra’s women protagonists have a timeless appeal. They wear their courage on their wings.