Sandhya Mukherjee was a national treasure, which we never saw - GetBengal story

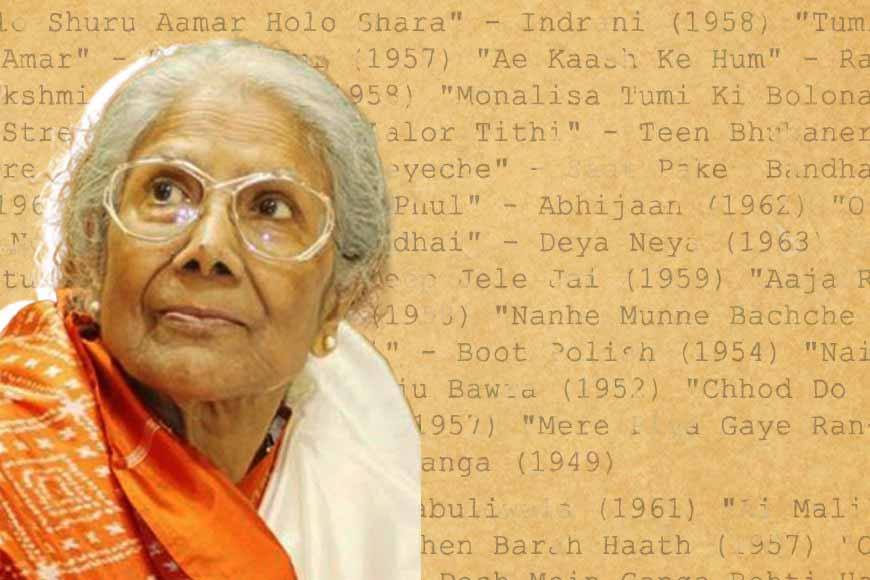

Legendary singer Sandhya Mukherjee

About a decade ago, I was coordinating a music video project involving 100 icons of Bengal. Naturally, Gitashree Sandhya Mukhopadhyay would be foremost among them. Having been warned that she was not particularly receptive when it came to anything other than music, I nevertheless called her residence with much trepidation. In her characteristic soft, almost whispery voice, she politely but firmly told me she was not inclined to be part of “any gimmick”, and wished us well. Such was the force of her personality that I didn’t dare say a word more.

When she turned down the Padma Shri last year, I couldn’t help but think back to that decade-old conversation, not to compare our very humble project with an award from the Indian Government, but to recall her absolute refusal to seek the spotlight in any way whatsoever. With her passing in Kolkata in February 2022 from heart failure, the last remnants of Bengal’s golden age of music are now lost to us.

Unfortunately, the spotlight trained on her refusal of the Padma Shri and the controversy that ensued, is probably what made her known to the rest of India, when she deserved to be an national legend, rather than simply a Bengali icon. Not that this bothered her in the least. She was probably the last of that breed of musicians for whom music is all that mattered. Everything that it brought with it, such as fame and money, was secondary.

Born in Dhakuria in south Kolkata in 1931, Sandhya Mukhopadhyay was attracted to music at a very early age. Having initially trained under such stalwarts as Pandit Santosh Kumar Bose and Chinmoy Lahiri, she went on to train under the legendary Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan and his son Munawar Ali Khan, which is what created her cast-iron base in Hindustani classical music. Only 14 when she recorded her first song in 1945, she graduated to playback singing three years later, singing Raichand Baral’s composition for the Bengali film ‘Anjangar’.

But music lovers in India ought to know that she sang for as many as 17 Hindi films too, thanks to the insistence of iconic singer-composer Sachin Dev Burman, who was instrumental in Mukherjee’s trip to Bombay in 1950, when her elder brother reached out to yet another legendary composer Anil Biswas. It was Biswas who gave the young Sandhya her first break in Bombay with the film ‘Tarana’ (1951), where she even sang a duet with Lata Mangeshkar, who passed away just about 10 days before Sandhya.

That duet was ‘Bol Papihe Bol Re’, a superhit of its time, and even a modern listener can easily distinguish between the girlish sweetness of Lata’s voice and Sandhya’s slightly huskier, heavier tone, despite the fact that she was actually two years younger.

However, there is absolutely nothing to separate them when it comes to skill, which is why it is truly a great pity that Mukherjee remains more or less undiscovered by the rest of India. Was it her aversion to the spotlight, or reluctance to ‘market’ herself, or simply her impatience with the bells and whistles of stardom that allowed her to remain confined to the background? Probably all of the above.

When it comes to Bengali music, it would be foolish to even attempt to list her achievements. Suffice it to say that without Mukherjee’s immortal contributions, the genre of ‘Bengali modern songs’ would not have been even half the institution it went on to become. As for playback singing, it could easily be argued that without the Hemanta-Sandhya pair, the legend of Uttam-Suchitra would never have taken off.

Lest anyone think Sandhya Mukherjee was simply a unidimensional singer who had no interests outside of her music, it should be remembered that during the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1970-71, she joined several other Bengali artistes to raise money for the millions of refugees who were pouring into Kolkata and West Bengal, and to raise global awareness for Bangladesh. She also helped Bangladeshi musician Samar Das to set up the Swadhin Bangla Betar Kendra, the underground radio station which broadcast to Bangladesh, and even recorded several patriotic songs for him.

When Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the leader of the new country of Bangladesh, was released from prison, Mukherjee recorded the song ‘Bangabandhu Tumi Phirey Ele’. She later became one of the first international artists to visit Dhaka, the capital of the new nation, performing at an open-air concert in Paltan Maidan to celebrate the first Ekushey February (International Mother Language Day today) after Bangladesh’s independence in 1971.

Typically, she moved away from the glare of the spotlight without any fuss. Nobody can really remember exactly when she stopped recording and singing in public, but as she gradually withdrew into retirement, nobody saw her go. It is our shared guilt that we did not make more of a fuss when she went, that we allowed her to go quietly. She had so much to give us, but we weren’t there to take it. It has been over a year that her journey ended. We can only mourn what we had, but didn’t know it.