Royal Bengal Tigers of Sundarbans: Casualties of our success and symbols of our failure – an exclusive interview with Joydip Kundu of SHER

The Sundarbans is the largest mangrove forest in the world, intersected by a complex network of tidal waterways, mud flats and small islands of salt-tolerant mangrove forests. It is also the home of the Royal Bengal Tiger and other threatened species such as the estuarine crocodile and the Indian python. The Sundarbans is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

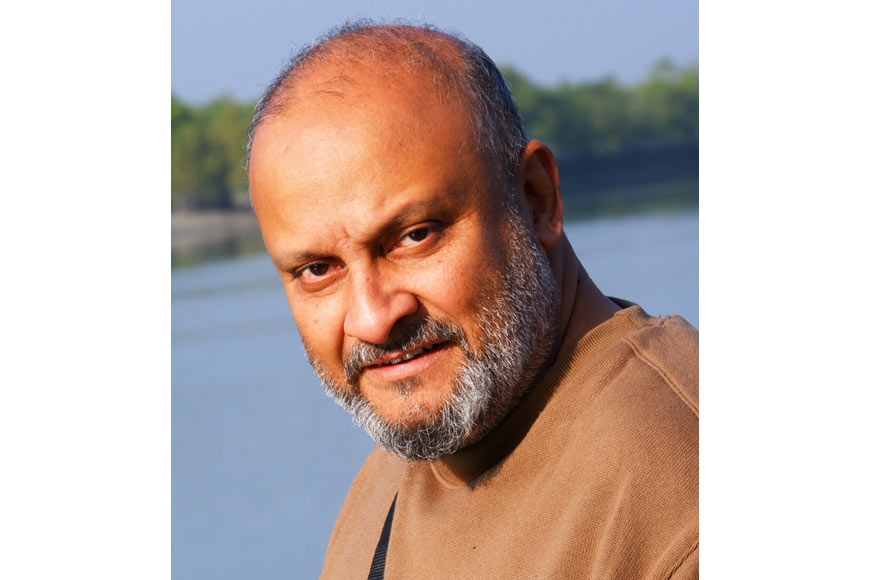

Well-known conservationist and founder of SHER (Society for Heritage and Ecological Researches), Mr. Joydip Kundu (J.K), has been working on various projects on human-wildlife conflict mitigation, conservation of wildlife, ecology and environment. His NGO is directly involved with various community projects in tandem with the forest department in the periphery of the Sundarban Tiger Reserve. His organisation has been working in the delta to provide alternative livelihoods for the forest-dependent marginal communities who share space with the tiger and his ecosystem as part of the tiger conservation project.

Joydip Kundu

Joydip Kundu

• GB: Recently declared escalated number of Tigers in the Sundarbans has raised hope among conservationists. According to the latest survey, the tiger population in the Sundarbans has already crossed 100. The forest department is obviously upbeat as years of hard work is finally paying off. But how has this success been achieved?

Joydip Kundu (J.K): You see, conservation is not a time-bound programme. This is a long-term teamwork between all the stakeholders of the Sundarban Tiger Reserve and is a continual process. The sublime management model and the protection protocol of Sundarban Tiger Reserve demand dexterity. Both were laid by some extraordinary forest officers in a uniquely intelligent way. We have to take one thing in mind that the landscape of the Sundarbans is one of a kind, that is, it is the only mangrove habitat that has tigers. The tidal hydrodynamics, extreme weather conditions, and frequent natural calamities make Sundarban a tough, really tough terrain. Above all, the Sundarban’s wild fisheries are the second biggest source of employment in eastern India that too within a mangrove ecosystem, countless numbers of people depend on forest resources. Thus, human-wildlife conflict is a predominant and inevitable feature of the Sundarbans.

Historically speaking, if we go back 10 years from now, we used to get frequent news of tigers crossing rivers or creeks and entering human habitats. This created a tussle between the man and the big cat. Again, if we go back another 20 years or so, bush meat (the prey animals of tigers) was easily available in the open village markets of those fringe villages at then-remote locations.

The Forest Department undertook a few groundbreaking measures to mitigate these extreme conflict situations. The foremost among these was the putting up of nylon net fencing and joint forest management (JFMC) initiatives. Putting up nylon net fencing at the village forest interface to limit interaction between villagers and tigers is a pioneering initiative that changed the history of tiger conservation in Sundarban forever. And secondly, the JFMC network. Joint Forest Management means involving the villagers who live on the periphery of the forests and who are the biggest stakeholder of the landscape. Communities from these peripheral villages have been made a part of the conservation effort under participatory management of Tiger Reserve and were formally introduced within Joint Forest Management (JFM) guidelines. FYI, the model of JFMC originated from West Bengal rather, West Midnapore district as an experiment module which was later adopted by the Government of India and became super successful. This balanced holistic approach and trust building with villagers through the JFMC network has started to give dividends in the form of reduced human-wildlife conflict situations since last decade. The rural stakeholders participated in the conservation effort through JFM committees constituted by TR authorities and local people derive direct benefits from sustainable use of forest resources. Numerous eco-development works like construction of jetties, brick paths, providing alternative livelihood support, skill development, plantation etc. has been benefitting the communities in great ways.

If the local people living in the periphery of protected areas do not get involved in conservation efforts, the forest and wildlife can’t be saved.

• GB: What measures were taken initially to sensitize and involve the villagers in tiger conservation schemes?

J.K: The Joint Forest Management of the STR runs the key tiger conservation efforts in the delta. Millions living in the fringe villages have grown to trust the forest field staff, who are the immediate friend in need coming to their aid in time of a crisis, be it large or small.

Providing civic amenities to villages does not come under the scope of the forest department but in Sundarban the goal of these welfare schemes is to create a trust building environment beneficial for not only the conservation of the tigers but the entire ecosystem. An entire community is benefitted just because they share space with Bengal Tigers and this fact has been well understood by the fringe-dwelling communities of Sunderban Tiger Reserve. This is an on-going process that is yielding results now.

• GB: Was it easy to convince the people living in the periphery of the jungles by simply getting them involved in developmental projects?

J.K: At the beginning the forest department and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) worked hard to take communities in their stride. Using different methods and modules, the villagers had to be convinced that if the tiger vanishes from the Sundarbans, miscreants will clear the mangroves forest in no time and if the protective barrier of the mangrove shield against cyclones is cleared, the entire southern Bengal would be exposed to the devastating cyclone and sea surges. Tiger is the guardian of the entire coastal Bengal. And this vital communication has reached the communities through the hard work of the foresters, various organisations and individuals who, over the years, have been campaigning to create this positive impact.

It is simple; saving the tiger is not just saving an animal but a means to protect the human-habitants of southern-most Bengal. If the tiger vanishes, so will the existence of human-population from Sundarbans. Climate disasters like Aila, Amphan, Sidr, etc. have been giving us signals periodically. Between the humans and the cyclones stand the mangrove-shield and between the felling of mangroves and the troublemakers stand the fear of the tiger.

• GB: What other measures have been taken to stall tiger encroachment in the villages?

J.K: Again referring to the early history of Sunderbans, in the past, the mangrove forests extended well beyond Kolkata. After the reclamation, the forestland was cleared and encroached by us humans. What used to be an undisturbed habitat of tigers once transformed into human settlements. Now there are villages bordering the entire tiger forest of Sundarban Tiger Reserve but there are no settlements within the border of the Protected Area. The forest-village interface at most places is separated by large or medium stretch of rivers or canals but at some places, the distance is extremely narrow. Tigers are territorial animals and always keep moving. They get very easily confused with the village side of the creek or the river as an extension of its habitat forest and enter the village mistakenly. Sometimes following territorial fights or pregnant female tigresses take shelter inside paddy fields mistaking them as their traditional mangrove habitat.

But of late, incidents of tigers straying into villages have seen a dramatic decline after erection of polypropylene net fencing on the forest-village interface stretching for more than 109 kilometers. The net has been tied with bamboo posts at a distance of two meters apart and the fencing is checked on a daily basis by patrolling teams of Tiger Reserve from individual beat offices under different forest ranges. The department adheres to this protocol to monitor the entire stretch and immediately restores in case of any wear and tear of the fence that is noticed. This is a unique concept that creates a physical barrier and a psychological barrier for the tiger, restricting its movement. This is indeed a huge achievement for the forest department. Since the Sundarbans is part of an international border, so with the help of the Border Security Force (BSF), the Forest Department undertakes joint patrolling on a regular basis. This has also helped in curbing illegal movement and poachers from entering our land to a great extent.

Another milestone in protection protocol initiated a few years ago is the E-patrolling. E-patrolling with GPS tracker is enabled through mobile of patrolling teams who move in boats within the canals and creeks and keep vigil and track animal and illegal human movements across the forest. Intensive patrolling by forest guards has helped in reducing the man-animal conflict to a great extent. In fact, now that we are all rejoicing at the growth of tiger population in the Sundarbans, this has been possible due to the concentrated efforts of the forest foot soldiers who risk their lives in this difficult terrain and thus the entire credit of this success in increasing tiger numbers must go to them.

• GB: But we do come across stray reports of tigers dragging isolated fishermen or crab hunters into the jungles. What measures have been taken to stop or minimize this trend?

J.K: A major issue that often leads to man-animal conflict stems from intense greed to earn some extra moolah. There is a great demand for crabs in foreign countries and even in the city markets of Kolkata and this is creating a lucrative source of generating additional income for the impoverished villagers. As a result, many villagers are risking their lives. They often endanger their lives and sneak into the forbidden territories stealthily for crab hunting and end up becoming prey of the predators. This is the biggest challenge for all conservation activists working in the Sundarbans. This man-animal conflict can be avoided only if we can provide an alternate source of livelihood for the villagers. Our organization SHER always works in close association with the forest department and takes up projects that can boost the existing schemes of the department so that the benefits can trickle down to the villagers. SHER focuses on strengthening the bond between the forest department and communities so that people can understand and appreciate the magnitude of the work the department is doing in inhospitable terrain.

• GB: What initiatives have you taken to provide alternative livelihoods for the locals?

J.K: We have set up a 1,400 square ft center named Baghbon in the Sundarbans and initiated an alternative livelihood programme for the women who risk their lives for hunting crabs. We want to minimize their forest dependence and have arranged to train them in tailoring. We are providing six-month training courses to each batch comprising 50 women so that they can be financially independent and are not forced to face dangers in the jungles in the future. One of our flagship projects has been with the fishermen of Sundarbans. Small groups of four or five fishermen usually go into the sea for fishing and remain onboard for days and weeks. During their days in the sea, they cook their meals using fuelwood. Sometimes, when they need to collect wood, they unknowingly tread into tiger territory and are exposed to danger. This often leads to man-animal conflict. To avoid this, we have collaborated with Sundarbans Tiger Project, and have provided mini-LPG cylinders to 100 licensed fishing boats. This is the first of its kind initiative in Sundarbans. We want the state government to consider our module and provide LPG cylinders.

• GB: Tiger conservation is a protracted on-going process. Please tell us how has the smooth functioning of the Sundarban management been possible?

J.K: A couple of extremely efficient senior forest officials have been working dedicatedly for years and their planning, leadership, foresight and involvement have boosted conservation initiatives in the Sundarbans in a major way. They have made significant contributions to the management of Sundarbans for a prolonged period. Dr Pradeep Vyas, IFS, was one of the longest-serving Field Directors of Sundarbans and Sundarbans Biosphere Reserve many of his management protocols are still very relevant and followed in forest management. Mr. Nilanjan Mullick came to Sundarbans as Deputy Field Director and later became the Field Director. A footprint of his conservation measures remains imprinted in the area. The present Chief Wildlife Warden, Mr Debal Ray, IFS, is taking all necessary measures to support the management. The present Field Director of Sundarban Tiger Reserve, Mr. Ajoy Kr Das, has vast experience working in the Sundarbans for a long time. Earlier, he was the Deputy Field Director of Sundarban Tiger Reserve and then went on to work as the Joint Director of Sundarban Biosphere Reserve before taking over as Field Director. His understanding of the landscape is invaluable and he is initiating many measures with his able team to ensure the protection of the tiger and its mangrove ecosystem.

• GB: Which areas need to be addressed to continue the progress in tiger conservation in the Sundarbans?

JK: The mangrove forests of Sundarbans are one of the most productive ecosystems and provide huge ecosystem services to the coastal communities. Its diverse flora and fauna, nutrient-rich creeks and canals are the most precious nature-reserve. Since changing of these natural habitats due to anthropogenic interference and climatic threats is pushing the Bengal Tiger and its ecology to an edge, people and policymakers must collaborate and take all possible initiatives to address the issues of this struggling mangrove biodiversity. In India, among three ‘Marine Biosphere Reserves’ the Sundarbans Biosphere Reserve is the most unique. There is a shortage of staff in the Sundarbans and that needs to be addressed by filling up the vacancies. Sundarban is a difficult terrain to manage and hence its protection and monitoring cannot be left under-staffed. The protection staff needs to be supported with modern-day technologies as well. The department is already taking up measures towards the same.

• GB: What is your organization SHER doing to support conservation in Sundarbans?

JK: As I told earlier, we focus on strengthening the bridge that connects foresters and the local people. SHER believes that winning over the fringe population of the Tiger Reserve area is the key to the conservation of such a unique and vulnerable area. Accordingly, SHER is constantly making people aware of the need to conserve this coastal bio-network through different modules of awareness generation campaigns, imparting nature education and promoting alternate livelihood options in coordination with Sundarban Tiger Reserve. Due to the remoteness of the area and lack of adequate infrastructure, it is impossible for the forest department alone to accomplish the conservation goal singlehandedly. Since SHER is operational on the entire stretch of over 25 villages located across the boundaries of the tiger forest, we have introduced a land-based Multipurpose Community Resource Centre for various resourceful activities that were desperately needed for some immediate and sustainable actions. We have started Baghbon, which is located on the opposite bank of Sajnekhali in Pakhiralaya village. This is the first-of-its-kind facility in the area that focuses on communication and stakeholders’ involvement. We have been working with the communities on the ground level to create a plan on how they can reach a better future and more sustainable resource use which will ultimately improve their lives. Simply by addressing many of the issues faced by the marginalized communities in these remote areas and providing alternative livelihood options has been a fruitful exercise. We have set up a capacity-building hub that is solely being used for capacity-building meetings, a workspace for vocational training for alternative livelihoods for villagers and imparting nature education for local children. Besides, with educational support, medical assistance, women empowerment activities, etc. Baghbon aims to involve a large section of locals who will play an important role in the restoration of the coastal ecosystem.

Mr. Joydip Kundu signed off with optimism in his words. Not all is lost yet, he assures. There is tremendous scope for ecotourism in the Sundarbans and its surrounding areas. The need of the hour is to develop sustainable eco-tourism and showcase our inheritance and all of us living in West Bengal should do our bit to further this cause.