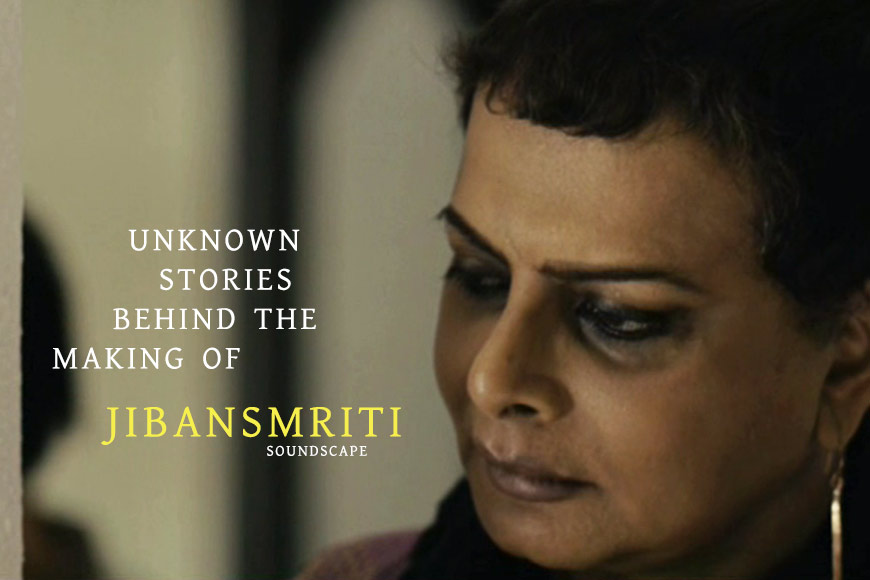

Rituparno Ghosh special, Part I: 'His bottom line was, I want it done’

Indrajit: Where and how did you first meet Rituparno Ghosh?

Prabuddha: I remember the first time he called me was on July 18, 2011. The date stands out because I had lost my mother just two days earlier. He told me he had started a project on which he wished to collaborate with me. I explained my situation to him and asked for a week's time. Seven days stretched to 14 before he called again, and we arranged to meet at his house. He said his project was on Rabindranath Tagore, and I was to be part of a script-reading session.

When I arrived at the house, I found several familiar faces. Ritu read the script of 'Jibansmriti' to us, following which we had an extensive debate and discussion session. I remember he specifically asked me what I thought of the script. To be honest, I hadn't formed an opinion yet, though parts of it did strike me as slightly strange. Ritu's film seemed to be about 'Rituparno Ghosh making a film on Rabindranath Tagore', in which he himself was a character throughout. In fact, our editor Arghyakamal Mitra bluntly asked what Rituparno Ghosh was doing in the film.

Ritu's answer was that Satyajit Ray had already made a documentary on Tagore, but that he, Rituparno, had been asked by the Central government to make another one to commemorate Tagore's 150th birth anniversary, with Shyam Benegal as project coordinator. His take was, "If I do it, I will do it my way. What's the point of making yet another, similar documentary? What can I offer that's new? The only way the two films can differ is in terms of treatment. It will be my way of paying tribute to Rabindranath. I will still talk about his life and works, but there will be a parallel stream within the film about a 50-year-old Rituparno Ghosh making a film on Tagore."

The significance here was that Tagore himself was 50 when he wrote 'Jibansmriti'.

Indrajit: What was your first impression at this one-on-one script-reading session? After all, any script is bound to create some sort of imagery. Also given the fact that you had seen quite a few of his films, what were your first thoughts?

Prabuddha: I wouldn't be too inclined to compare his earlier films with this one, since this was a documentary. Still, his reading of the script, as well as the imagery and detailing that he talked about, brought two things to mind: one, he knew exactly what he wanted. There was to be no groping in the dark. Two, he seemed to be focusing more on the visual aspects such as location, and the exotic aura of Rabindranath, rather than on him as a world poet and musician. The philosophy embedded in Tagore's poems, songs, and other writings, or the fact that he was so far ahead of his time, didn't seem to attract Rituparno as much.

Instead, for example, he mentioned how there would be a storm in a particular scene, or how a caged parrot would suddenly call out...

Indrajit: Would you say Rituparno's background in advertising, and the role that packaging plays in it, was a contributing factor in his desire to create a visual extravaganza?

Prabuddha: Not exactly. Rituparno did start his career in advertising, but by the time we met, he had spent far more time in cinema. And while he did make a mark in advertising, he did not spend a lifetime with it. I can relate to this all the more because of my own advertising experience. In recent times, l may have gravitated toward cinema to a greater extent, and cut down on my advertising work, but in 2011, I was definitely known as an 'ad man'.

I would say Rituparno's work certainly bore traces of the discipline, as well as certain techniques, that advertising teaches you. However, what he was trying to do in the Tagore documentary went deeper than that. I believe a film about an iconic figure like Tagore is bound to falter when it comes to conveying the depth of his philosophy and vision. That kind of thing is always easier for a reader to understand, as opposed to a viewer.

So what Rituparno did was adopt a technique whereby his film would be a recreation, in which someone would play Tagore through four stages of his life, and others would play members of his family, such as Kadambari, or Debendranath. In my opinion, he deliberately adopted the docudrama format because he didn't want to make just a documentary with endless voiceovers, heavy on philosophy, which would basically cover no new ground, and hence fail to retain viewer interest... it would sound more like an audiobook.

Instead, he went for a docudrama that would capture actual episodes in Tagore's life, which Ray partially did in his documentary. Rituparno carried that approach to far greater lengths, and put in the additional dimension of a successful Bengali filmmaker making a documentary on Tagore. In my opinion, such an approach would, per force, cause any filmmaker to focus more on the visual aspect, instead of the analytical. In any event, it is impossible to encapsulate Tagore in a two-hour film. Even Satyajit Ray chose to highlight certain aspects of Tagore's life, such as his message of world peace, or his humanism, to a far greater extent than his contribution to music, say. I believe this was because Ray realised that 90 minutes would be sorely inadequate to portray all of Tagore. And Ritu felt the same way.

Indrajit: While listening to the script, were you working out a soundscape in your mind?

Prabuddha: The only thing I felt was - and I told Ritu as much - that I was not going to derive my music from Tagore's, or create a leitmotif based on his sound. If a Tagore composition was used in the film, it would be an original in its pure form. There was an exception to this, eventually, but I'll come to that later.

My idea was, given Tagore's status as a global citizen, a docudrama on his life would feature an entirely different kind of music, as befits any work of world cinema. When I put this to Ritu, I wasn't sure how he would react, but he seemed fine with it, and told me to go ahead as I saw fit. In fact, early on, I had asked him, why me? I was hardly an expert on Tagore or his music, why did Ritu want to work with me? His response was, my not being a Tagore expert was the exact reason why. It would give me a fresh approach to the subject.

As work got underway, he told me he needed a few playback pieces to begin with. And that led to a strange experience. In one particular sequence, Ritu wanted to show his team, including me, on a recce of Jorasanko Thakurbari. Some portions of this sequence were shot in the actual Thakurbari, the rest in a set designed to look like it.

Now Ritu had decided to use the song 'Gahana Kusum Kunja Majhe' from 'Bhanusingher Padaboli' as we were inspecting the Thakurbari, but there was no mention of this in the script, so I knew nothing about it. This was fairly typical of him. Very often, he showed a total disregard for established shooting norms and conventions. His bottom line was, "I want this done."

Anyway, when we reached the Thakurbari, he told me, "Listen, I'd like to use this song." The music that I would have to create would provide a rhythmic accompaniment for Rituparno Ghosh walking through the Thakurbari, and coming upon the child Rabindranath, followed by a slightly older version of him.

And then he asked for something which at the time seemed incomprehensible. His brief to me was, this song would distil the exotic essence of 'Bhanusingher Padaboli', so I would have to explore ways to reinvent it, break it up, reconstruct and arrange it, stretching myself to the limit. And the reason for this was, Ritu was casting himself as Radha, while Tagore was Krishna, and each would be seeing the other through that prism.

Very frankly, at first I thought it was a totally weird idea. But this was Rituparno Ghosh, who had created his own space, and was by then well on the road to his gender transformation. The sequence would feature Radha and Radha alone, no gopinis or anyone else. And immediately afterward, there would come a storm. Whether it was a storm of passion, of devotion, or love, was open to interpretation. But the sound of the storm would emerge from the exotic sounds of 'Gahana Kusum Kunja Majhe'.

The entire film was about a few recurrent motifs, which I found interesting. Among them was the theme of Rituparno Ghosh, transforming himself from man to woman at the age of 50, and the mindset behind that transformation, which his work was beginning to reflect. This was not a hurdle as far as I was concerned, but the flavour that this imparted to the work was not something I was used to.

Nonetheless, Ritu's vast knowledge of Rabindranath and his work, his razor sharp intelligence, and abnormally strong instincts worked in his favour...

Indrajit: Taking a cue from that, since Rituparno knew far more about Tagore than the average Bengali, and given the depth of his academic insights, I feel that a work on Tagore was an opportunity to visually execute Rituparno's own sense of association with Tagore's thoughts and vision...

Prabuddha: Of course... why else would he include himself in the film? But a very strong addition was the gender transformation that Ritu was going through, and the artistic expression of that transformation.

Indrajit: So what did you do with the song?

Prabuddha: To begin with, I didn't make it a solo. Though the gopinis were unseen, I wanted to create the impression of a crowd. Hence the chorus, but in order to break it up, I used Kaushiki Chakraborty's voice in the form of a few taans. I gave the song a tonic shift in order to fit it into raga Kalavati, though the original is nowhere near Kalavati. There were three major instruments playing, and 16 layers of guitar, which I played, having changed the tuning completely, basically counter-tuning it. Essentially, the guitar was the main instrument, but it couldn't be played using European note patterns, so I changed my technique, almost playing it like a sitar, with that resounding fullness.

Alongside, I inserted layers of khol and pakhawaj, though the khol was marginal. With this came a flute.

One other interesting thing about Ritu was that he took a long time to emerge from the euphoria of a job well done, or one that he had liked doing. Immediately before 'Jibansmriti', he had finished 'Chitrangada', and he had a trunk full of ghungroos (ankle bells) from that film, which he had asked me to use as and when possible.

Now 'Gahana Kusum Kunja Majhe' was recorded in two studios. I recorded the vocals and guitar in one studio, and the khol, pakhawaj, and all the assorted ghungroos, whose combined weight must have been 60-70 kg, in another studio. I used the ghungroos in two ways - one, by striking them directly, and two, like wind chimes. We would string them up between two pillars inside the studio, and run our hands over them, using multi-locational microphones to record. It took us an entire shift just to record the ghungroos.

Indrajit: Was Ritu present at these recording sessions?

Prabuddha: Only for the songs, never for the background music.

to be continued...