Rich beyond belief: How the wealthy of Calcutta spent their fortunes

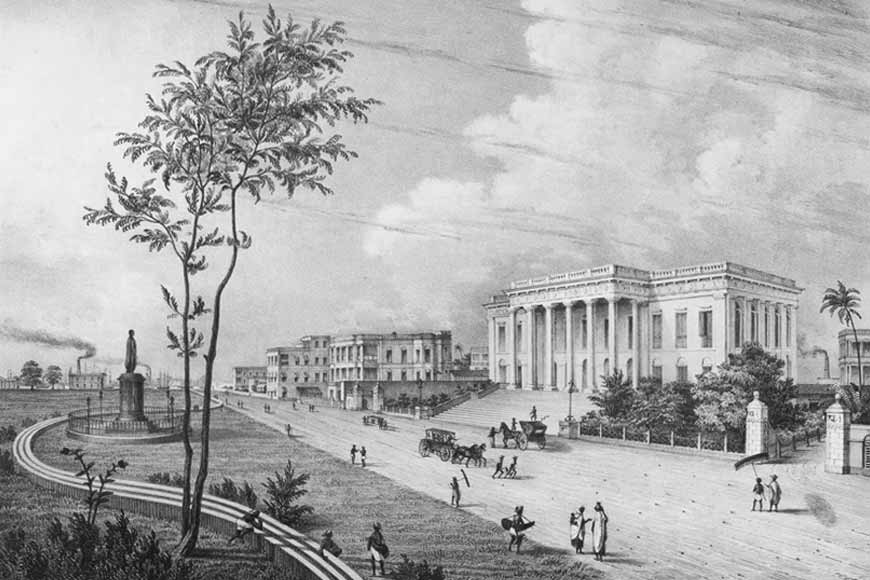

Town Hall

Europeans in Calcutta. This one topic has generated so many books, essays, articles, photographs, and other documents that one could probably fill half a library with them. Ironically, a lot of this documentation has been produced by Indians, who have failed to do the same for the ‘natives’ living in the city at the time. Consequently, we know very little of how Calcuttans lived, earned and spent their money, how they entertained themselves, their food, clothes, and so on, until the first half of the 19th century, when the earliest Bengali newspapers began to be published.

The dribs and drabs of information we have managed to acquire from the 18th century, however, do tell us a few things. About affluent Bengali society at any rate. We know that many members of this class were engaged in business with the British East India Company, or working for them, and making huge fortunes in doing so. How huge? To take just one example, in September 1818, a news item announcing the death of Babu Gopi Mohun Tagore stated that he had left behind a fortune worth Rs 80 lakh!

Even earlier, the Calcutta Gazette dated April 12, 1792 had this to say: “On Monday last died suddenly Cossinaut Baboo, a very opulent native and a man of a fair and respectable character. His remains were burnt the same evening according to the rites of the Hindoos, in a pile of Sandal and other rich wood, at the ghaut which bears his name. Cossinaut Baboo is said to have died worth upwards of 60 lakhs of rupees, which he has divided among his four sons.”

Kashi Mitter Burning Ghat

Kashi Mitter Burning Ghat

‘Cossinaut Baboo’ was Kashinath Mitra, an immensely wealthy merchant who later became Dewan to the Kasijora Rajbari of Medinipur. The burning ‘ghaut’ (ghat) in his name is Kashi Mitra Ghat crematorium in Bagbazar, which exists to this day.

How did these super rich Bengalis spend their money? Very lavishly, is the answer. The ostentatious displays at weddings and funerals, or during Durga Puja, left most of their British business partners speechless with amazement. They also invested considerable amounts to set up banks and other commercial establishments, and in buying land or other immovable property. To give credit where it is due, many of them also furthered the cause of English education by setting up schools, textbook societies, and publishing houses, and donated funds for the spread of women’s education and other social causes. The still more philanthropic-minded built roads, bridges, ghats, temples, and dharamshalas, or guesthouses for pilgrims.

When it came to art and culture, too, many wealthy Calcuttans spent large sums of money in maintaining ‘Jatra’ (traditional stage performances based mostly on history and mythology) troupes and other entertainers. Those familiar with Utpal Dutt’s iconic Bengali play ‘Tiner Talowar’ may recall Babu Birkrishna Dawn, the owner of Great Bengal Opera.

In fact, it was thanks to these wealthy citizens of Calcutta that the first amateur theatres were established. In 1881, for instance, Prasanna Kumar Tagore opened the Hindu Theatre, where amateur performers staged the plays of William Shakespeare in English, and Bengali adaptations of ancient Sanskrit plays. It was from such amateur theatres that the professional stage of Kolkata gradually evolved.

Dwarkanath Tagore

Dwarkanath Tagore

Yet another Tagore, Rabindranath’s grandfather Dwarkanath, bought the plot of land which housed the ill-fated Chowringhee Theatre, destroyed by a fire in 1839, for the then princely sum of Rs 15,000. In later decades, many such purchases proved to be absolute goldmines for the descendants of those wealthy men, as the value of real estate rose to astronomic heights.

Many of these properties were frequently rented out to the British, at fairly steep rates. For instance, old Supreme Court records show that a house belonging to Ramrutton (Ramratan) Tagore, which stood “on the Esplanade, to the east of the Court House”, which is approximately where Town Hall stands today, was let for Rs-300 per month to a few company officials. Later, an advertisement appeared in the Calcutta Gazette offering to let the house at “a monthly rent of Rs 500 which is reduced from Rs 600”.

Inevitably, such wealth brought with it an attendant lifestyle, which would be unaffordable even by today’s standards. In its edition dated February 12, 182o, the Samachar Darpan announced: “Babu Ramdulal Sircar has notified in the Government Gazette that his two sons will be married on the 7th and 11th Falgoon and that the 1st and 2nd Falgoon, have been fixed for the entertainment of the European guests, and the 13th to 16th Falgoon for Hindu, Arab and Mogul guests, to attend at his house at Simla to dine there and see the naulches and other entertainments provided.”

In the Calcutta Gazette dated September 27, 1737, it was reported that “Neemoo Mullick, the rich Banker, is said to have spent lately three lakhs of rupees in the sheraad, or funeral ceremony of his mother’s death. It is on these occasions that the most parsimonious Hindous incur great expense.”

Similarly, Sambad Kaumudi reported on May 14, 1825 that “in a notice of the death and funeral ceremony of Ramdulal Sircar, it is stated that famous Pandits were brought from Benares, Kashmir, Maharastra, Kanauj, etc., numbering about seven to eight thousand to grace the occasion, and that the gifts bestowed on the occasion included golden and silver utensils, elephants, boats, carriages, etc. It is also stated that several lakhs of destitute people received alms of a rupee each, so that on this item alone, several lakhs of rupees were spent”.

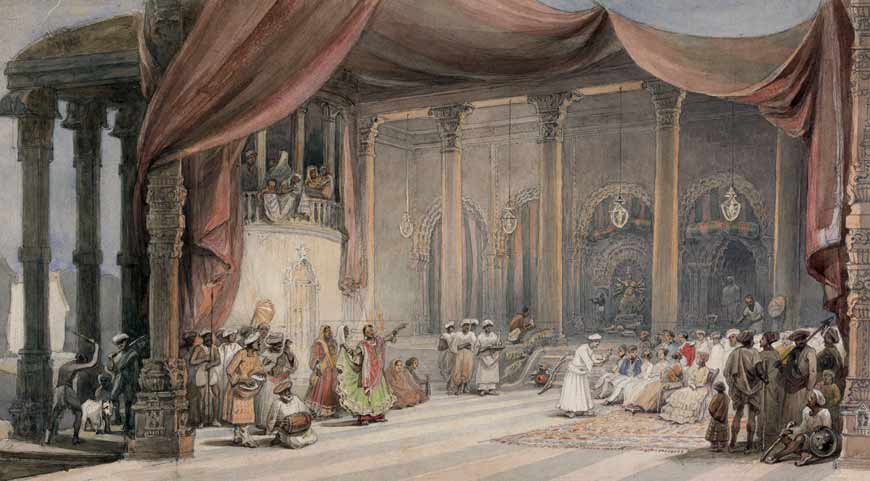

As for Durga Puja, literally no expense was spared. The Calcutta Gazette had this to say on October 20, I8I4, “The Hindu holidays of the Doorga Poojah began yesterday and will continue until the 25th instant. Many of the rich Hindoos, vying with one another in expense and profusion, endeavour by the richness of their festivals to ‘get a name amongst men’. The principal days of entertainment are the 20th, 21st and 22nd, on which Nikhee,* the Billington of the East, will warble her lovely ditties at the hospitable mansion of Raja Kishun Chand Roy, and his brothers, the sons of the late Raja Sookh Moy Roy. Nor will the hall of Neel Money Mullick resound less delightfully with the affecting strains of Ushoorun, who, for compass of voice and variety of note, excels all damsels of Hindusthan. Misree, whose graceful gestures would not hurt the practised eye of Parisot, will lead the fairy dance on the boards of Joy Kishun Roy’s happy dwelling. At Raja Raj Krishna’s may be viewed with amazement and pleasure, the wonderful artifices and tricks on legerdemain of an accomplished set of jugglers, first arrived from Luckuow.”

William Prinsep, Europeans being entertained by dancers and musicians

William Prinsep, Europeans being entertained by dancers and musicians

Nikhee, by the way, was a renowned dancing girl of the time, and a report in a Bengali publication dated October 16, 1819 describes how “There was a dancing girl in Calcutta, named Nikhee. A gentleman of fortune, being very much pleased by her singing and dancing, has now engaged her at a monthly salary of Rs 1,000.” That this was news worth reporting ought to tell you how highly the myseriously named Nikhee was esteemed by contemporary Calcutta society.

Another newspaper report from 1829 states that Governor-General Lord Bentinck, Commander-in-Chief Lord Combermere, and many other Englishmen attended Durga Puja festivities at Sovabazar Rajbari. As the Pujas come up this year, it is easy to cast the mind back nearly 200 years ago, to a time when the lavish entertainments accompanying the festival kept not merely the ‘sahibs’ happy, but generated business worth crores for their ‘native’ trading partners.