Re-looking at the glory that was ‘Mankar Rangmahal’

In this fast-paced, city-centric life, not many people are perhaps aware of the tiny hamlet Mankar, tucked deep inside Galsi I CD Block of Purba Bardhaman (East Burdwan) district of West Bengal, which is steeped in history. This non-descript village was once a thriving town with a rich legacy of literature, art, and architecture. According to local belief, the Pandavas lived in hiding at Mankar during their Agyatvas (spending exile period in disguise). There is an ancient temple dedicated to the Pandavas with the idols of the five Pandava siblings in Mankar.

Mankar was once renowned as the ‘Temple town’ of Bengal. Between the mid-18th and late-19th centuries, about 42 brick temples of different sizes were built in the distinct architectural style of Bengal with chala, ratna, and dalan. From early records, we get to know that the town’s growth and development started at the beginning of the 19th century when weavers came from different parts of Bengal and settled there. They were masters in their craft and created the once-renowned tussar silk and also weaved kutuni, similar to a double jersey fabric with silk on one side and cotton on the other. They weaved fishing lines as well. At the beginning of the 19th century, the flourishing town had a population of 1,500, and half of them were expert weavers.

Today, Mankar’s fame rests primarily on its giant-sized kodma, a gooey, hard cracked semi-round shaped sweet made of sugar which is an essential offering to deities during pujas. People from far-off cities and towns troop to Mankar to buy huge, puffed kodma, the size of a pumpkin but weighing only 500 gms, as an essential part of puja rituals. These are in great demand during community festivals like Saraswati, Lakshmi, Kali, and Durga Puja. However, of late, the sweetmeat has lost much of its charm due to a lack of competent karigars (sweetmeat makers) and also because of its excessive sugar content.

The earliest records of Mankar’s history take us back to more than 500 years ago. The zamindars of Mankar were high-caste Brahmins who hailed from Kanauj aka Kanyakubja, an ancient town in central Uttar Pradesh. The ancestor of this dynasty was Dubey aka Dwivedi, a native of Kanauj. His successors were Manorath Dubey and Srikant Dubey. Srikant Dubey left his hometown and migrated to Chandrakona in Midnapore after initiation (diksha) to the Radhaballav Sampraday in Mathura. He received the title of Goswami and from then on, his descendants came to be known as Goswami. His descendants were Madhusudan Goswami, Niharidas Goswami, and Shyamsunder Goswami. Pandit Shyamsunder Goswami initiated (Guru Diksha) Vaishnavism to Maharaja Jagatram Rai and his wife, Brajkishori Devi, of Burdwan and came to live in Khandari village near Mankar.

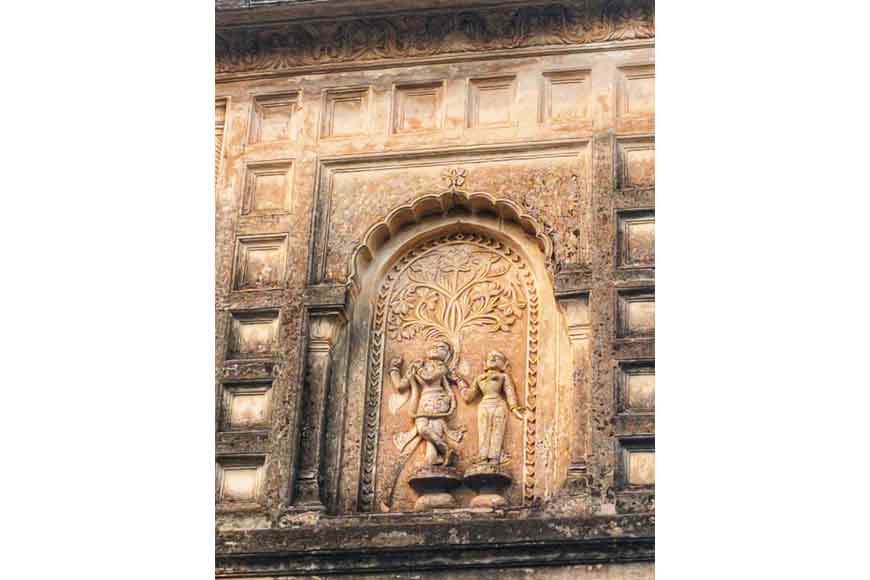

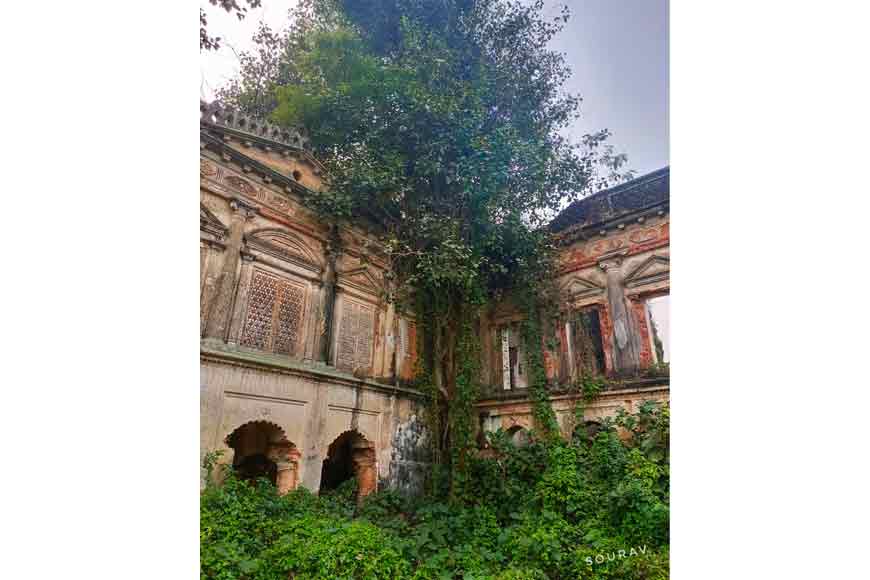

Shyamsunder Goswami’s son, Bhaktalal Goswami, initiated (Guru Diksha) to Maharaja Jagatram Rai’s son, Maharaja Kirti Chand Rai, and his son, Chitrasen Rai (1702-1740). As Guru-dakshina (fee to teacher) in 1129 BS (1722 AD), the Maharaja donated the tax-free village of Mankar Raipur to Pandit Bhaktlal Goswami. Pandit Bhaktlal Goswami became the first landlord of Mankar Raipur and built a palatial house called Rang Mahal. This was once part of the sprawling Radhaballabh temple complex. The deity 'Radhaballav Jew' was placed in the newly-built Navaratna temple on the day of Uttarayan Sankranti in 1135 BS, (1729 AD). At present, the area is teeming with wild vegetation and the main pinnacle of the temple, which has some brilliant stucco work, along with a pair of small octagonal temples are the only structures still standing. Bhaktalal Goswami also built the Singhabahini temple. Apart from Mankar, the family had two more estates in Bharatpur and Khandari villages.

Bhaktalal Goswami was a much-revered learned man and his presence attracted many erudite Brahmins from different parts of the country to convene in Mankar and settle there. Bhaktalal Goswami was succeeded by Brajlal Goswami, Setablal Goswami, and Ajitlal Goswami. They all played major roles in the growth and development of Mankar.

Ajitlal was succeeded by his grandson, Hitlal Mishra. He was the only son of Dhankumari Devi, daughter of Ajitlal and Haripriya Devi. Hitlal Mishra was the most accomplished zamindar of this dynasty. He was a man of many talents. His erudition, wisdom, generosity, and foresight were amazing. He spent generously on the development and infrastructure of his estate. He had an astute business sense and was the owner of indigo factories on his estate. He was also the kuloguru (guru or spiritual leader of a race or tribe) of the Burdwan royal family and a prolific author who wrote numerous books including commentaries on the Srimad-Bhagavatam which was highly praised by none other than Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay. Chattopadhyay wrote in ‘Bongodarshan, “The Bengali ‘tika’ (note) can be of two types. One is the Bengali translation of the ancient commentary by learned men and commentary on those changes. Second, a new Bengali annotation can be written. Some have adopted the first practice. Babu Hitlal Mishra has compiled a summary of his commentary, sometimes a summary of Shankara's commentary, and sometimes a summary of Sridhar Swami's commentary. The Bengali readers are especially indebted to him for that.”

Mishra had a fetish for collecting hand-written manuscripts and established a Bhagavatalaya in his house to collect books. His vast collection of manuscripts in the Bhagwatalaya was unmatched in the entire Burdwan district. In the introduction to the essay, 'Srimadbhagavatgita,' author Bankim Chandra mentioned his indebtedness to Hitlal Mishra’s works. Mishra was an educationist who established a number of tols and chatushpathis (tols and chatuspathis were centers for higher education in Sanskrit). It was during his tenure that education was given a boost in Mankar. Mishra honoured scholars who were held in high esteem during his tenure and learned men like Gadadhar Shiromani, Narayan Churamani, and Jadabendra Sarvabhaum flourished in Mankar.

Zamindar Hitlal Mishra was an erudite and liberal man and he was secular. Although he was a Hindu zamindar, in 1860, he built a mosque for the Muslims. He also donated 15 bighas of tax-free land and a pond for practicing Islamic rituals. He also established a Church near the present hospital (Mankar Hospital). His contribution to the establishment of Mankar High School was undeniable. Hitlal Mishra laid the foundation stone of Mankar Haat-tola.

The British government had undertaken to build and repair the existing road on the Mankar-Budbud stretch, but work was going at a snail’s pace. There was a time when the road became impassable due to the delay and Mishra ventured to complete the task himself. He used his resources and got his men to repair the road and planted hundreds of palm trees on both sides for beautification. By 1873, there was a famine in the Mankar region. The situation became deplorable due to food shortages and the water crisis. Hitlal Mishra came to the rescue and played an important role. In order to alleviate the water crisis, he built Krishnaganga Dighi in imitation of Krishnasayar of Burdwan. He built a total of 12 ghats around it. And for beautification, a wide variety of trees were planted around the lake.

Hitlal Mishra's only son Jagadish Mishra died at the age of 28. Hence, in 1879, his daughter's son and his grandson, Rajkrishna Dixit succeeded Hitlal Mishra as the landlord of Mankar. He was a brave man and was anti-British. At one time, he banned the use of British goods in his zamindari. In 1905, when Lord Curzon declared the Partition of Bengal, anti-British sentiment spread like wildfire, and Mankar, too, joined the protest movement. Rajkrishna Dixit, who was then the zamindar of Mankar Rangmahal, joined the anti-Partition movement and publicly doused British-made commodities in the boycott movement that followed. He was immediately put under arrest. Dixit was the first Zamindar of Bengal to be imprisoned for joining the Swadeshi movement. The Hitabadi organization felicitated Dixit with an ivory stick, silver medal, and shawl. Dixit was very proactive and assisted the revolutionaries in various ways. His son, Radhakanta Dixit succeeded him and like his father, Radhakanta was also an ardent freedom fighter.

The British government came down heavily on the insurgents and most freedom fighters went underground. They maintained contact with different groups secretly and Mankar Rangmahal was a safe center for the revolutionaries. Rebels including Jadabendra Panja, Nirod Mitra, Jiten Chowdhury, Girija Prasad Bhattacharya, and Fakir Chandra Roy used to visit Rangmahal secretly and discuss with Dixit their next tentative move. Radhakanta Dixit helped them with funds as well and secretly sold parts of the zamindari to raise funds and help the freedom fighters. Radhakanta Dixit died at the age of 32 and after his demise, his wife Shaktibala Devi adopted Kanchan Kanti Dixit. He was the last zamindar of Mankar Rangmahal. Gradually, the sunset on Mankar’s transcendently impressive past and its history and contribution to the freedom struggle was forgotten and the town was relegated to the annals of history.

Photo courtesy Sourav Kesh