Rabi babu and Subhas, a bond that endured

In 1925, a 27-year-old Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose was arrested and sent to a British prison in Mandalay, Burma, there to remain for the next two years. At about the same time, back home in Kolkata, iconic Bengali novelist Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay published his ‘Pather Dabi’ (soon to be banned by the British-Indian government), about the life of a young Bengali revolutionary imprisoned in Burma.

Writing to Chattopadhyay in this context, Subhas observed, “Had I not come here, I would probably never have realised how much I love my ‘sonar Bangla’. It is as though Rabi babu wrote those words precisely for the captive condition…” The reference, obviously, is to Rabindranath Tagore’s song ‘Amar Sonar Bangla Ami Tomay Bhalobasi’, which went on to become the national anthem of Bangladesh.

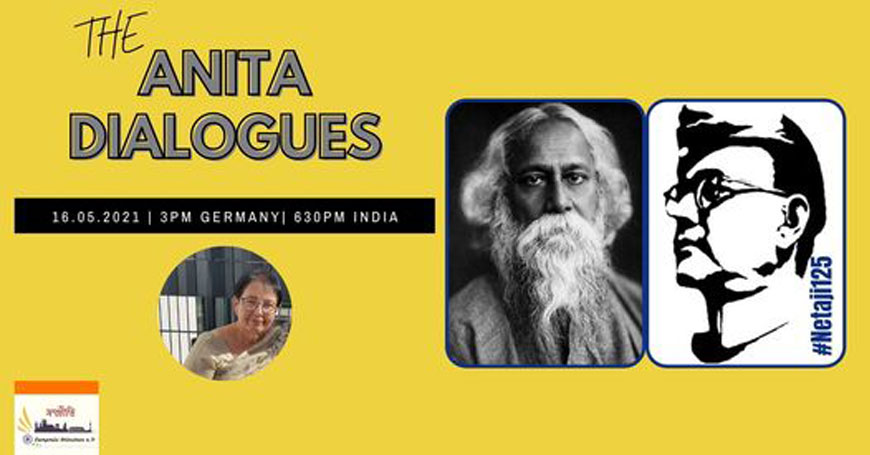

This and other anecdotes about Tagore and Subhas are at the crux of ‘The Anita Dialogues’, a series of monthly conversations with Netaji’s daughter Dr Anita Bose Pfaff, who lives in Germany. The fourth edition of the series was recently aired on YouTube, May being Tagore’s birth month. The conversations are hosted by Sampriti, an organisation of Bengalis in Germany, to mark the 125th year of Netaji’s birth. They will continue until February 2022, and are being moderated by Sampriti’s founder and current president, Shaibal Giri.

The discussion with Dr Bose Pfaff brings to the fore the somewhat curious relationship between Netaji and Tagore, both iconic in their own way, despite their widely varying mindsets and the 36-year age gap between them. As a teenager, writing to his elder brother Sarat Bose, Subhas was effusive in his enthusiasm for Tagore. “What strange people we (Bengalis) are!” he wrote. “We have so little reverence in us. I am stung by self-reproach when I think how indifferent Bengal has been in showering laurels upon him.”

Only a few years later in 1914, however, the same Subhas came away unimpressed after meeting his idol in person for the first time at Santiniketan. Tagore had won the Nobel Prize in 1913, and the young firebrand had perhaps expected a more transformative encounter. Instead, the celebrated poet advised Subhas and his friends about the importance of developing a rural way of life, which clashed directly with the young man’s ideas about industrialisation.

And so it went. By an extraordinary coincidence, the two met again in 1921, aboard a passenger ship of all places. Subhas had just resigned from the elite Indian Civil Service (ICS) in order to come back from England and join the freedom struggle, while Tagore was on his way back from his tour of the US and UK. In 1919, shocked and horrified by the Jalianwalla Bagh massacre, Tagore had renounced the knighthood conferred on him by the British. Meeting Subhas on the ship, he congratulated the young man for his courage in resigning from the ICS.

But as Dr Bose-Pfaff points out, the political views of the two men were often at odds. Most notably in their approach to Mahatma Gandhi, whose relationship with Subhas often verged on the acrimonious. In 1935, for instance, Subhas wanted the foreword to his autobiographical work ‘The Indian Struggle’ to be written by H.G. Wells or George Bernard Shaw, and requested Tagore to contact them on his behalf.

In his letter, he wrote: “I had also thought about you but I am not sure whether you would be willing to write on my political book. You have also turned into a blind admirer of Gandhiji recently - one gets that impression from reading your recent writings… I am not sure whether you would tolerate any criticism of Gandhiji.” To which Tagore wrote back: “Gandhiji is a tremendous moral and ethical force which, if I do not respect it, will make me ‘blind’.”

By the late 1930s, however, the relationship had improved considerably, particularly in the light of Gandhiji’s express desire to prevent Subhas from becoming president of the Indian National Congress for a second term, and the political manoeuvres which eventually led to his resignation from the Congress. Tagore publicly took Subhas’ side, and declared him as the ‘Deshnayak’ in 1939.

It is perhaps fitting, as Shaibal points out in this episode, that India saw both these men for the last time in 1941. In mid-January, Subhas escaped from India in dramatic fashion, never to return. And on August 7, Tagore breathed his last at his ancestral home in Kolkata’s Jorasanko. But one of his last works had been a short story titled ‘Badnaam’, whose protagonist Anil crosses Afghanistan, as Subhas did.

Subhas never forgot either, as Dr Bose Pfaff points out. Through the Free India Centre, which Netaji established in Germany, ‘Jana Gana Mana’ was played and sung for the first time in Hamburg on May 29, 1942, alongside the German national anthem. And a Hindi adaptation of what would become India’s national anthem also became the anthem of the Azad Hind Fauj, Netaji’s liberation army.