Purity first: Bangladesh's attempts to rediscover Nazrul

“Almost every day, some artiste or the other sings my songs on the radio. Fortunately or unfortunately, I listen to them too… most of the gentlemen and ladies, finding my songs and music helpless and alone, do such a thorough job of mauling them that they seem to breathe their last on the spot. It really does become a fight between sur (music) and asur (cacophony).”

“Why must we make changes to Nazrul Sangeet to apparently suit today’s generation? Why can’t they change their mindset to appreciate the music as it was originally composed? Do we change Beethoven’s music just because we think young people will find it appealing?” asks Khairul Anam Shakil,

Khairul Anam Shakil and his wife Masuda Anam Kalpona

Khairul Anam Shakil and his wife Masuda Anam Kalpona

The above is a rough translation from Bengali of an excerpt from an article by one of Bengal’s greatest cultural legends irrespective of borders, Kazi Nazrul Islam. Writing in the 20 August, 1928 edition of the publication ‘Nabashakti’, Nazrul was obviously expressing his indignation at the way contemporary artistes were distorting his songs and music, and later on in the same article, went on to criticize “radio artistes who don’t take the trouble to kindly learn the music and lyrics of my songs”.

For millions of Nazrul’s admirers on both sides of the border, the distortions that the legend himself was painfully aware of have continued making their presence felt. And the resulting controversy has never really died down either, much the way Rabindranath Tagore’s songs have come in for their share of ‘experimentation’ and ‘innovation’, creating fierce, near-hysterical arguments both for and against.

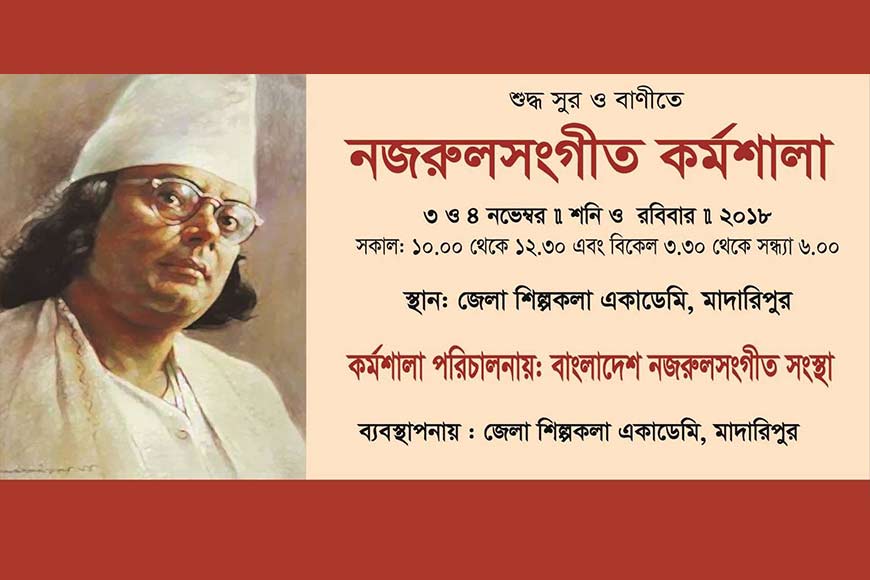

Details of a workshop which was held in November 2018

Details of a workshop which was held in November 2018

“Why must we make changes to Nazrul Sangeet to apparently suit today’s generation? Why can’t they change their mindset to appreciate the music as it was originally composed? Do we change Beethoven’s music just because we think young people will find it appealing?” asks Khairul Anam Shakil, one of Bangladesh’s most renowned Nazrul Sangeet (or Nazrul Geeti as it is more commonly known on this side of the border) exponents today.

Along with his wife Masuda Anam Kalpona, also a noted Nazrul Sangeet exponent, Shakil and quite a few others have made it their mission to restore the purity of Nazrul Sangeet, and make the originals more accessible to young learners today. To that end, their organisation, Bangladesh Nazrul Sangeet Songstha (BNSS) has already made considerable progress in their attempts to popularize the songs in their original form, traced back to the years before 1942. That was the year when, at the age of 43, Nazrul was diagnosed with an irreversible neurological disorder which gradually robbed him of speech and caused his behaviour to become increasingly erratic, until he finally stopped working altogether following his wife Pramila’s death in 1962.

As Kalpona tells it, BNSS is currently engaged in creating a repository of all the original ‘swaralipi’ (written note patterns, equivalent to sheet music in Western terms) that they have been able to locate, uploaded to Google Drive, from where anyone can access them. As of now, this treasure trove contains nearly 1,500 songs. That apart, the organisation has also created a spreadsheet full of YouTube links to numerous original songs, which Shakil, Kalpona, and the other members encourage their students to follow. Of particular help in this regard has been a YouTube channel run by Shiraj Shnai, which contains several original recordings, some even made during Nazrul’s lifetime.

A child recieving a certificate.

A child recieving a certificate.

Are students receptive to their efforts? Kalpona says one of their biggest challenges is to make some students ‘unlearn’ the songs they have picked up from listening to famous artistes.

That apart, outreach programmes have helped the organisation hold online workshops and classes across various districts of Bangladesh, designed to familiarise students with Nazrul Sangeet as he composed it, not necessarily as it has been sung by artistes through the years. Neither, says Shakil, as they are being interpreted today by ‘fusion’ artistes. “Take a song like ‘E Ki Aseem Piyasa’, which is based on Raag Tilang and set to Teentaal. I saw a TV show in which this song was accompanied by Western drums, playing a 4x4 beat. This isn’t fusion or value addition, you are actually changing the form of the song. That is simple disrespect,” he says.

Are students receptive to their efforts? Kalpona says one of their biggest challenges is to make some students ‘unlearn’ the songs they have picked up from listening to famous artistes. “The problem is that once you have heard the distorted version from a really skilled artiste, it is difficult to get it out of your head,” she says. Shakil’s take on the matter is, “The students are very keen, but I don’t think we as teachers have always been able to reach them. It is our duty to convey to them the heights to which luminaries like Tagore and Nazrul have taken our music and our culture.”

As Shakil points out, “This generation needs to move closer to Nazrul, not move away from him.”

For those not fully aware of his life and work, Nazrul himself was an expert on Hindustani classical music, and actually created as many as 18 new ragas, which he sadly never had the time or opportunity to popularise. Alongside, his music reflects several other genres, ranging from ghazal and thumri to Shyama Sangeet and kirtan. “Before you experiment with any of these genres, as Nazrul himself did, you must know it fully. Otherwise, what fusion are you creating?” asks Kalpona.

Masuda Anam Kalpona with her students of the workshop

Masuda Anam Kalpona with her students of the workshop

Unlike West Bengal, where the number of artistes dedicated exclusively to Nazrul Geeti has noticeably decreased over the years, Bangladesh still has artistes who sing nothing else. Nazrul’s determinedly anti-fundamentalist and astonishingly inclusive writings, his repeated imprisonment for his outspoken criticism of British imperialism, and the depth of his cultural explorations once inspired entire generations of revolutionaries, including freedom fighters in both India and Bangladesh. His message remains as relevant today as it was all those decades ago. As Shakil points out, “This generation needs to move closer to Nazrul, not move away from him.”