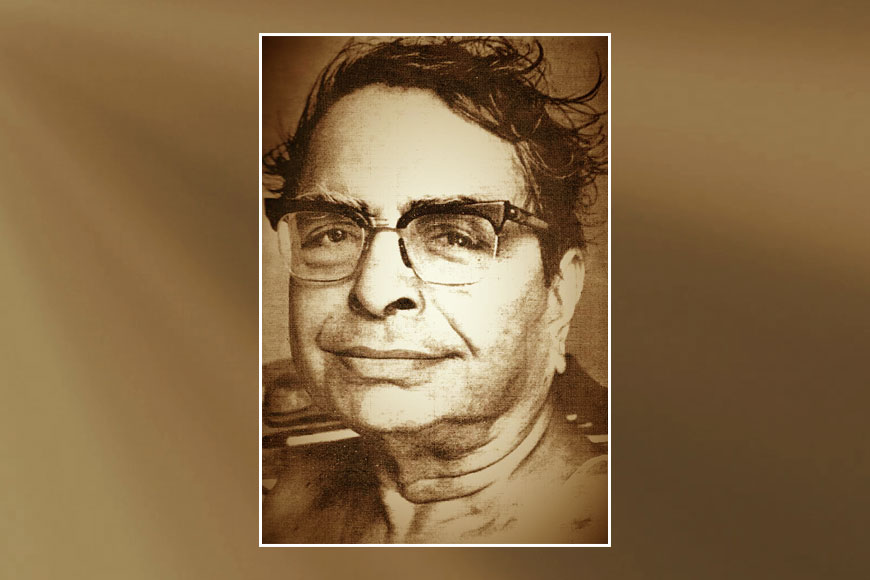

Peeping into the life of Bonophool, the master story-teller

Wildflower is symbolic of the free spirit. Uncultivated by the mainstream, an independent thinker, bravely growing wild and free in a world plagued by conformity. Dr. Balaichand Mukhopadhyay chose the pen name ‘Bonophool’ (wildflower) when he commenced his journey as an author. A qualified pathologist and medical practitioner, he shot into prominence as a novelist, poet, playwright, and short story writer representing the neo-modernist Bengali literature that started with the famous Kallol literary movement.

Authors belonging to the Kallol group tried to introduce pragmatic and dynamic prose that would articulate social conflicts rather than seek only the sublime. However, the movement had its snobberies and promoted a Calcutta-centric urban culture and language. Mukhopadhyay was born in Manihari (July 19, 1899), a village in the Purnia district of Bihar. He was educated and spent a major part of his life in Bihar. As soon as his writings began to appear in renowned journals of the time, they garnered readers’ interest but he was made to feel like an ‘outsider’, a non-resident Bengali author by his urban contemporaries belonging to the Kallol camp who weighed his literary works as peripheral to Bengali literature.

Bonophool made his distinct mark in the realm of short stories. His stories are really short with snappy tangy punches, piquant, and vitriolic. He aimed to demolish the pretentious snobbery of the Bengali city-bred elite as being superior in values and morals to the subalterns who live in villages or work at the bottom of the rung in cities as menial labourers.

Dr. Mukhopadhyay chose Bonophool (wildflower) as his pen name, one that truly expressed his angst at being ‘looked down on’ by the city. However, he had a pan-Indian fandom and many of his novels and short stories were made into films, both in Hindi and Bengali. Mukhopadhyay’s virtuosity lies in story writing. He wrote 61 novels and 600 short stories. He had diverse interests and his plots cover a wide range of subjects including history, anthropology, medicine, psychology, and love. His novels and short stories reveal intricate sensitivities of human relationships. Mukhopadhyay was a free-spirited soul born with a Bohemian streak who did not always bother to comply with conventional societal norms. During his college days in Kolkata, he lived in a men’s hostel (mess bari) in Patuatola Lane. Once, his classmates who lived in the same hostel had fever. He needed nourishment to recover fast but the meals served in the hostel were inedible and not the right stuff to entice the appetite of a convalescent patient. Mukhopadhyay sprang to action. He took out a plate from the community kitchen and rushed out of the mess. Before his inmates could fathom his intentions, he returned with a full plate of a home-cooked, piping hot delicious meal for his friend. Later it transpired that he had gone to a stranger’s house in the neighborhood and had asked for a home-cooked meal for his ailing friend. His simplicity and honesty impressed the lady of the house and the family gladly complied with his request. This was Bonophool, a whimsical and unfathomably friendly man who could go to any extent to help people whom he loved and cared for.

Also read : Banaphul -- The master storyteller

When he was a student at Calcutta Medical College and Hospital, he lived in the vicinity of the college at the International Boarding house, located at the crossing of Mirzapur Street and Harrison Road. One day, his friend and inmate of the hostel were writing a letter to his newly-wed wife when he had to rush out to attend to some other business. The incomplete letter lay open on the desk. Bonophool noticed it and with his wild and wicked sense of humour, he instantaneously jumped into action. He copied his friend’s handwriting and wrote the rest of the letter. This was just the beginning of his mischievous prank. Dressed as a servant in a simple dhoti and short kurta (photua), he went barefoot to his friend's in-laws' house and delivered the letter. Soon after the letter was delivered, all hell broke loose at the hostel as messengers from his friend’s in-laws’ house started frequenting the boarding house in batches, demanding the son-in-law visit his wife. Even his father-in-law landed there and requested his son-in-law to visit their home and meet his wife. One might wonder about the content of the letter that jolted the friend’s in-laws’ family into action. It was again an instance of a playful prank by Bonophool. He had impersonated his friend and written to his spouse thus: “I am very keen to visit your house but feel very embarrassed to go on my own without a formal invitation from your folks. So, if your parents and relatives write to me and invite me, I can go. Yours …” Only an idiosyncratic genius like Bonophool could have pulled a peculiar prank on his friend like this.

During the same time, Bonophool was an inmate at the International Boarding, he shared his room with one of his distant cousins who was studying in a medical school. To facilitate his cousin’s understanding of human anatomy, Bonophool used to collect human parts of the body like the brain, lungs, heart, kidneys, etc from the medical college and bring them to the boarding house, dip them in formalin and preserve them in clay pots which would be stacked neatly under the cots. And right next to the collection, the duo would cook mutton in a cooker. There were times when the severed body parts were not fully immersed in formalin and the rotten stench of human flesh permeated the room but Bonophool would remain unaffected and would go about his daily routine in the most prosaic manner.

Once, a girl’s father came to meet Bonophool with a marriage proposal. He was disinterested and made it clear, but the gentleman was persistent and requested him to meet his daughter once. Bonophool tried his best to dissuade him but to no avail. Finally, he said bluntly: “If I wish to get married, I shall definitely not look for the size of the girl’s nose or skin colour. Instead, I shall examine her blood, sputum, and urine reports. My minimum conditions to marry someone include…” and then he rattled his conditions before the gentleman who sat dumbfounded before him. Bonophool said, “The person I intend to get married to has to be a female and needs to be a matriculate. I am least interested in the physical features of a girl.”

Dr. Mukhopadhyay chose Bonophool (wildflower) as his pen name, one that truly expressed his angst at being ‘looked down on’ by the city. However, he had a pan-Indian fandom and many of his novels and short stories were made into films, both in Hindi and Bengali. Mukhopadhyay’s virtuosity lies in story writing. He wrote 61 novels and 600 short stories. He had diverse interests and his plots cover a wide range of subjects including history, anthropology, medicine, psychology, and love. His novels and short stories reveal intricate sensitivities of human relationships.

This was the kind of outspoken man Bonophool was. He had an innate child-like simplicity and boyish innocence that were an inherent part of his persona. He never really cared for norms set by a ‘polite, upper-crust civilized’ society. Sometimes he would be immersed in his inner world for days and during that phase, his daily routine would go haywire. He would go around in torn and tattered clothes, unshaven profile, performing his duties but oblivious of his looks. He would even stop bathing and worked on an empty stomach for days in the end.

Bonophool made his distinct mark in the realm of short stories. His stories are really short with snappy tangy punches, piquant, and vitriolic. He aimed to demolish the pretentious snobbery of the Bengali city-bred elite as being superior in values and morals to the subalterns who live in villages or work at the bottom of the rung in cities as menial labourers. In his novels and stories, the ordinary people who belong to the peripheral region of society, always seem to be one up on the elites, and despite their simplicity, they stand out as more honest, spontaneous, and integrated people.