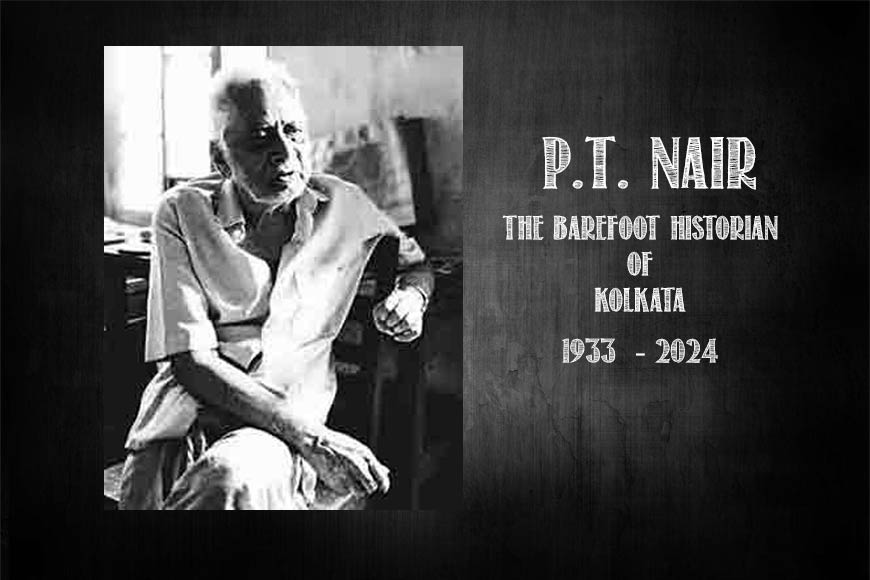

P.T. Nair, the Barefoot Historian of Kolkata is no more – GetBengal story

The Barefoot Historian of Kolkata has passed away, but he leaves behind a legacy of around 70 books that meticulously chronicle the histories of several streets, neighbourhoods, and landmarks in the City of Joy over the course of fifty years. At the age of 91, P. Thankappan Nair went away from his village, distant from the city he loved, from illnesses associated with ageing. Nevertheless, he endures in the recollections of those who had the opportunity to hear from this "walking talking encyclopaedia" about the city he fell in love with. P. Thankappan Nair, who was 91 years old, died of natural causes in his hometown, which was far from the metropolis he loved. However, he continues to exist in the recollections of those who had the opportunity to hear from this "walking talking encyclopaedia" about the city he fell in love with. And this was long before Google Maps began to interfere with our lives, before armchair heritage enthusiasts appeared on the urban landscape with the goal of "saving Kolkata's historic buildings," and even before armchair heritage enthusiasts were born.

The fact that Parameswaran Thankappan Nair was a Malayali who arrived in Ernakulam, Kerala, for his higher studies—a city that had previously been home to a large South Indian population—and that he was neither a Bengali nor raised in Bengal made his background all the more surprising. Nair was born in 1933 at Manjapra in Ernakulam district, near Kalady, where Adi Sankaracharya was born. His usual attire was a simple shirt and sandals, and he would go around the city on foot, chronicling its history. He did not gather his information from archives, libraries, or the internet. He simply walked around neighbourhoods and started gathering data. He did it purely out of love and passion, and till the end, he never hankered for any publicity, though several historians sought him out for his huge bank of knowledge about the city. In order to find the untold experiences and write about them in his book, he even ventured into obscure neighbourhoods. He left behind a wealth of historical records, similar to Feluda's Sindhu Jyatha, which have been consulted by several other historians, scholars, and aficionados for the city's legacy.

After completing his higher studies in Kolkata, he got a job as a typist—a particularly good one at that—and fondly kept his antique Remington for years. Then he switched to journalism, and his penchant for history landed him a job at the Anthropological Survey. Though the job was a well-paying one, it meant PT had to leave Kolkata, something he never wished to do. By then, he was already in love with this city and had been collecting its historical documents, so he took one of the biggest decisions of his life by quitting a plush job. His love for this city was so potent that he was willing to leave a secure job just to go back to the streets that had adopted him. He was a humble man. He lived in a small rented room filled with thousands of books in a locality in Bhowanipur’s Kansaripara Lane. But his treasure lay in the books he collected over the years; many of them were rare and probably the last editions of books written. He used to buy them from second-hand shops at the Dharamtala-Wellington crossing and College Street. His collection went up to around 3,000 rare and valuable books, which he later sold to the Kolkata Municipal Corporation (KMC) before leaving the city. He collected documents on Job Charnock from Fort St. George in Chennai, which dispelled myths about the man who reputedly founded the city of Kolkata. The books are preserved today in the Town Hall library.

He was so humble that he met everyone who dropped by his house and narrated enjoyable historical tales about the city. One could also find him at the National Library, where he spent a sizeable part of his day reading lost texts that were kept in the lockers, gathering dust. Other than some research scholar or history student who would hunt these texts down for notes, there was hardly anyone like PT Nair who did it just out of a passion for knowledge. The National Library staff knew him very well, almost like one of their own. Those who have been to the National Library know how difficult it is to find a book one is looking for, as it is literally a labyrinth of books and scrolls. But for PT, books on Kolkata were at his fingertips.

Then he began to write because it was the only way he could generate money while still leaving behind documentation about the city. He wrote more than 40 English volumes on the social life and history of Kolkata, with a focus on the city's streets. His notes were written in plain English. He felt quite at ease writing in Malayalam for some of them.

Even after returning to Ernakulam after 63 years in Kolkata, he continued to read books and newspapers and engage in farming activities, his younger son, Manoj Nair, a school teacher, told the press. “In his mission, he was a self-less seeker of truth and a human being who represented a great detachment from the lures of money and position,” says P.A. Sojan, who has been long associated with him.

PT Nair recalls his early days in one of his books: “From the day I came to Calcutta, I started taking an interest in it. Whenever I saw a building or monument, I started collecting material on it—in depth—from other sources. I took the tram from Kalighat to reach my office in Dalhousie Square, which has not changed much in the last 50 years. No new building has come up except for Telephone Bhavan. But the city has changed very much, in the sense that the days of political turmoil are over. There are a few processions, and now I can sleep peacefully. All heritage buildings must be preserved and strengthened. Other buildings that have no heritage status can be demolished. Beautiful buildings should be preserved. If the owner can’t preserve it, the government or the corporation should come forward to preserve it. Old buildings can never be built again.”