One woman against a mighty establishment, the Mamata Banerjee saga

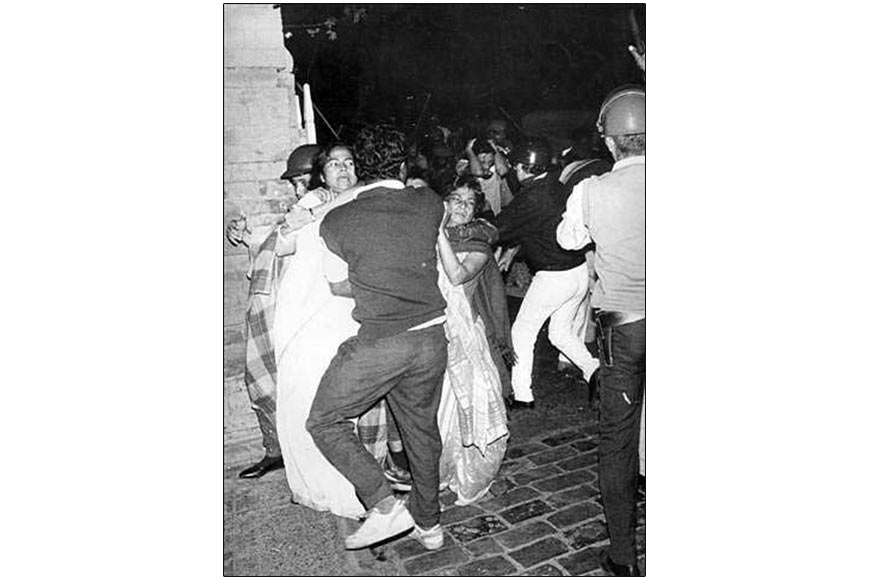

There was a time in West Bengal when public meetings of the Left Front would invariably feature somebody or the other saying: “The red flag will fly in Bengal for as long as the sun shines.” After 35 years, all it took to lower that flag was a single woman, a politician with the instincts and aggression of a street fighter, a woman who many Left-leaning intellectuals in particular often publicly ridiculed as an ‘uneducated slum dweller’.

That woman is, of course, Mamata Bandyopadhyay. On International Women’s Day, the purpose is neither to lionise nor crucify her, but simply to acknowledge her achievements as a lone woman challenging predominantly male bastions. In her signature Dhanekhali taant (cotton) saris and flip-flops, she took on the might of an entire ruling establishment which had been entrenched in the state for over three decades, and ultimately emerged victorious despite a continuous stream of attacks, both physical and verbal. As both industry and agriculture went into a downward spiral during Left rule in Bengal, Mamata’s straightforward messages and forthright manner resonated with urban and rural populations alike.

Schemes such as Kanyashree, Swasthya Saathi, Sabuj Sathi and many others have drawn international recognition and awards. And the cooperatives operated by women in rural Bengal have made the state a forerunner in the country in terms of employment generated by MSMEs, according to Central government data.

Her political career really took off in 1984 when, as a 29-year-old Congress candidate, she handed the seemingly invincible Somnath Chatterjee his only defeat in 11 Lok Sabha elections, a shocking upset which nobody had foreseen, particularly from Calcutta South, that stronghold of the Bengali elite. In those days, it was common to see Mamata scour every lane and by-lane of her constituency on foot, a plump, slightly dishevelled figure, waving to the people who had come out on balconies to watch her pass. Women in particular seemed to love the young, unconventional politician, the elderly among them often calling out their blessings and messages of support from the balconies.

Today, as India’s only serving woman chief minister, she faces what is possibly the toughest electoral test of her career, in the upcoming Vidhan Sabha or state Assembly polls. Over 33 days and 8 phases (the most for any state this time), these elections are shaping up to be an intense battle, and the bottomline seems to be: a bevy of central ministers, including the Prime Minister and Home Minister, at least six chief ministers, and various central agencies, versus one woman in Hawaii chappals. At least, that is how the narrative has played out so far.

Mamata is now past 65, but these elections seem to have brought her old street fighter instincts to the fore once again. On the one hand, she is up against India’s richest political party which is also in power at the Centre, the BJP, and its politics of religion. On the other, there is the Left-Congress-ISF combine. On a third front, she will need to battle the anti-incumbency factor after 10 years of a Trinamool Congress-run administration, particularly the allegations of corruption against party members despite her own clean image.

Many of those party members, including a few prominent ones, have deserted her and switched to the BJP, which the Trinamool’s election campaign has targeted as a party of “outsiders”, seeking to impose an alien culture on Bengal. To counter all of that, Mamata has already embarked on a frenetic series of visits, from Nandigram to Nadia, Kolkata to North Bengal. Her party’s primary tagline of ‘Maa, Maati, Manush’ has now taken on the additional slogan of ‘Bengal wants its own daughter’. While she openly admits that many have let her down, she is telling voters to “look at me and vote”.

Mamata Bandyopadhyay. On International Women’s Day, the purpose is neither to lionise nor crucify her, but simply to acknowledge her achievements as a lone woman challenging predominantly male bastions.

Throughout her life, like many Indian women, she has battled the odds. Her party’s 10-year scorecard, though not spectacular, does include significant achievements in governance, thanks to a series of well-chosen bureaucrats, and frequent business summits with industry leaders in an attempt to woo them back to the state. Along the way, she has had to battle a host of negative perceptions about Bengal that took hold during the Left Front’s tenure, but she has successfully combined shrewd political manoeuvres and administrative intervention to combat some of them.

Schemes such as Kanyashree, Swasthya Saathi, Sabuj Sathi and many others have drawn international recognition and awards. And the cooperatives operated by women in rural Bengal have made the state a forerunner in the country in terms of employment generated by MSMEs, according to Central government data. Today, thanks to initiatives like ‘Biswa Bangla’, Bengal’s handicrafts have found a steady global market. Given that 49 percent of West Bengal’s voters are women, the move to field 50 women Trinamool candidates in the upcoming elections is yet another wise move.

Accusations of minority appeasement notwithstanding, considering 30 percent of the population is Muslim, West Bengal remains one of India’s most peaceful states, communally speaking, other than sporadic incidents like Malda, which were quickly brought under control.

While her artistic and poetic endeavours have come in for their share of ridicule, the fact remains that the state government does run schemes to support impoverished artistes with pensions. And almost every regular visitor to Kolkata agrees that the city has received an aesthetic facelift over the last decade. Whether all of that will translate into enough votes is for the future to decide.