On International Day of Non-violence, remembering ideas of Mahatma

In January 2004, Iranian Nobel laureate Shirin Ebadi had proposed to the United Nations for an International Day of Non-Violence and he suggested October 2, the birthday of Mahatma Gandhi to be declared as The International Day of Non-Violence. Since the UN declaration, Gandhi’s birthday is observed as an occasion to "disseminate the message of non-violence, including through education and public awareness". The resolution reaffirms "the universal relevance of the principle of non-violence" and the desire "to secure a culture of peace, tolerance, understanding and non-violence".

How do we define violence? According to World Health Organization (WHO), violence is the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community, that either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, mal-development or deprivation. The definition encompasses interpersonal violence as well as suicidal behaviour and armed conflict. It also covers a wide range of acts, going beyond physical acts to include threats and intimidation. Besides death and injury, the definition also includes the myriad and often less obvious consequences of violent behaviour such as psychological harm, deprivation and mal-development that compromise the well-being of individuals, families and communities.

But why is there so much of violence? Each year, over 1.6 million people worldwide lose their lives to violence. Violence is among the leading causes of death for people aged 15–44 years worldwide, accounting for 14% of deaths among males and 7% of deaths among females. For every person who dies as a result of violence, many more are injured and suffer from a range of physical, sexual, reproductive and mental health problems. Moreover, violence places a massive burden on national economies, costing countries billions of US dollars each year in health care, law enforcement and lost productivity.

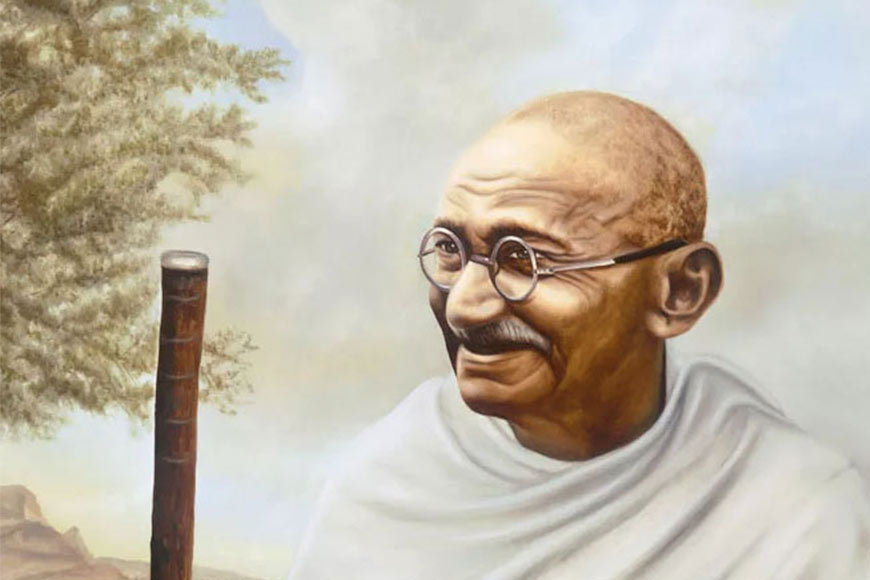

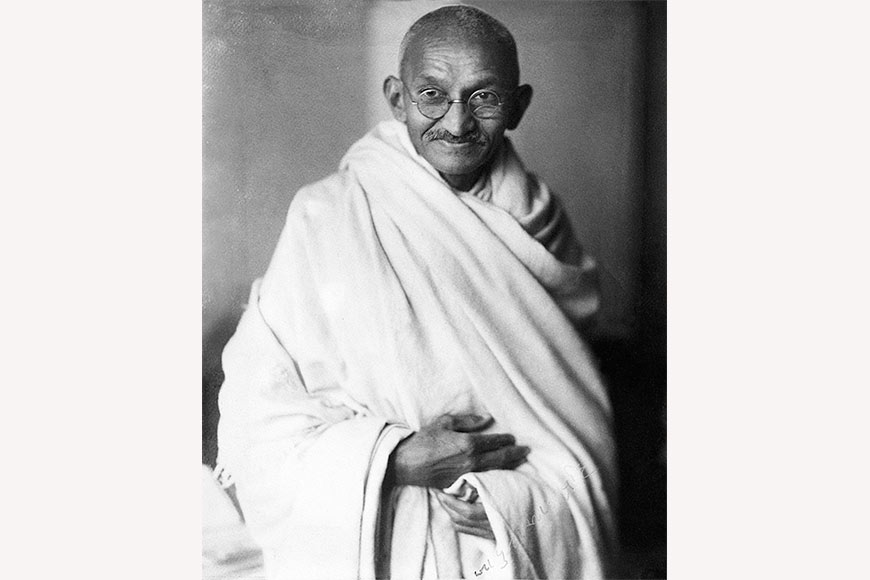

Father of the Nation

Father of the Nation

The modern era is characterised by unprecedented, and well documented, mass killings. While war-related casualties and other human driven violent episodes have experienced a dramatic increase throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, it is the 20th century that has, so far, been the pinnacle of mass slaughter in human history.

The two world wars together with the genocides, revolutions and other mass killings, including the systematic destruction of one’s own populations have resulted in around 200 million deaths worldwide. Furthermore, organizational and ideological developments have made mass killings easier to undertake and legitimize, while technological advancements have quickened this process. For example while Tsarist Russia executed less than 4,000 individuals accused of political crimes during a period of 85 years, the Soviet NKVD killed around 700,000 political prisoners in a few months with an average of 1,000 executions per day.

The speed and scale of mass killings in the Nazi death camps was even more staggering: in Majdanek extermination camp 18,000 Jews were killed on November 3, 1943 in a few hours. No pre-modern state had the organizational and technological means to destroy this many people in such a short period of time.

Although conventional wars and revolutions have recently been replaced with civil wars and insurgencies, there is no sign that violence as such is decreasing. For one thing, the proliferation of nuclear weaponry has made global annihilation an ever-present daily possibility while also making some traditional forms of political violence redundant in this process.

While organized violence has experienced a transformation wherein the relative decline in direct war fatalities is now replaced with the ever increased coerciveness of states and non-state organizations, the expansion of military spending, the development of selective and strategic killing systems, the unprecedented scale of population displacements, staggering incarceration rates, worldwide increase in suicides, the opioid epidemics and the irreparable destruction of the environment leading towards very likely future wars over scarce resources. As the UNHCR documents, there are currently 68.5 million forcibly displaced people in the world, which is the highest number ever recorded

Homicides are becoming more frequent in some parts of the world, while gender-based attacks are increasing globally. The long-term impact on development of inter-personal violence, including violence against children, is also more widely recognized. Separately, technological advances have raised concerns about lethal autonomous weapons and cyber-attacks, the weaponization of bots and drones, and the live streaming of extremist attacks. There has also been a rise in criminal activity involving data hacks and ransomware, for example. Meanwhile, international cooperation is under strain, diminishing global potential for the prevention and resolution of conflict and violence in all forms.

Homicides are becoming more frequent in some parts of the world, while gender-based attacks are increasing globally. The long-term impact on development of inter-personal violence, including violence against children, is also more widely recognized. Separately, technological advances have raised concerns about lethal autonomous weapons and cyber-attacks, the weaponization of bots and drones, and the live streaming of extremist attacks. There has also been a rise in criminal activity involving data hacks and ransomware, for example. Meanwhile, international cooperation is under strain, diminishing global potential for the prevention and resolution of conflict and violence in all forms.

This is the time when the world needs to adopt the Gandhian concept of non-violence (Ahimsa) which is not merely confined to resisting the practice of violence. It involves removal of hatred, animosity and any thought of violence from the mind. Non-violence is an expression of tremendous power of mind and soul over brute force. It is not enough to desist from the practice of violence. One must uproot violence entirely from the heart with all-embracing power of love and universal fraternity, as a matter of uncompromising principle in life. As Gandhi would emphasize, through violent means, both victory and defeat become sterile. The more the weapons of violence, the more misery to humankind. The triumph of violence ends in a carnival of mourning for departed ones.

These words are prophetic and in these unnatural times, the name of Mahatma Gandhi transcends the bounds of race, religion and nation-states, and emerges as the prophetic voice of the 21st century.