Notir Puja: Rabindranath Tagore’s Only Film Nears Century

Few outside West Bengal, or even inside the state, are aware that Rabindranath Tagore directed a film based on Notir Puja, a dramatized version of his long poem Pujarini, written in 1899. Notir Puja or its original long poem offer different perspectives on death in its varied manifestations. In its essence, Pujarini is the 2,500-year-old story of a ‘noti’ or, in its Sanskritised form, ‘nati’ (danseuse), who sacrifices herself for her faith in the Buddha and Buddhism.

Pujarini was recast in dramatic form as Notir Puja in 1926. While on the one hand it indicated Tagore’s continuous interest in, and reverence for Buddhism, on the other, the change in form – from poetic to dramatic – brings into sharper focus the dramatic elements in the story. There is a shift in emphasis from the martyr to martyrdom. At the core of the story, one can discern the omnipresence of the spirit of Buddha, which Tagore falls back on repeatedly in his poems, plays and songs.

However, though Tagore took the story from the Buddhist series in Abadan Shatak (some say it is from the Pali sacred book), he deviated from the source. Srimati, a court dancer, becomes a follower of Buddhism, which is forbidden in the kingdom. However, so deep is her attachment to the Buddha that she is not afraid to die, a sentiment which her king treats with deep sarcasm and anger. Her inner strength and moral courage seem to instil a sense of diffidence and inferiority among the majority, who used to look down on her as a court dancer. They accuse her of being egoistic and insolent, which she is not. In fact, Tagore wipes out any hint of insolence in his play.

Srimati’s glory lies in her ability to rise above her social status by drawing sustenance from the soul and in dedicating herself to the will of the Buddha. Tagore’s deviation from his source marks out his way of investing the conventional concept of martyrdom with a completely new dimension. This raises Srimati from her marginal space of an outcaste within the royal framework. Not consciously or by design, but purely through her devotion to the Buddha.

Notir Puja is not a dance drama, but Srimati’s final dance recital defines its dramatic essence. The drama turns out to be a build up to Srimati’s final dance, not to appease royalty, but as a spontaneous expression of her complete devotion to the Buddha. The dance ends with the death of Srimati, which redefines the very concept and ideology of martyrdom.

Tagore’s daughter-in-law Pratima Devi had expressed her desire to stage an all-woman play in 1926 following the Bengali New Year celebrations. She requested Tagore to dramatize Pujarini, and thus was born Notir Puja, staged for the first time in celebration of Tagore’s birthday on the 25th day of Baisakh that year. The venue was Uttarayan, Tagore’s residence at Konark, Santiniketan. Gauri, daughter of noted painter Nandalal Bose, created history with her performance in the title role of Noti.

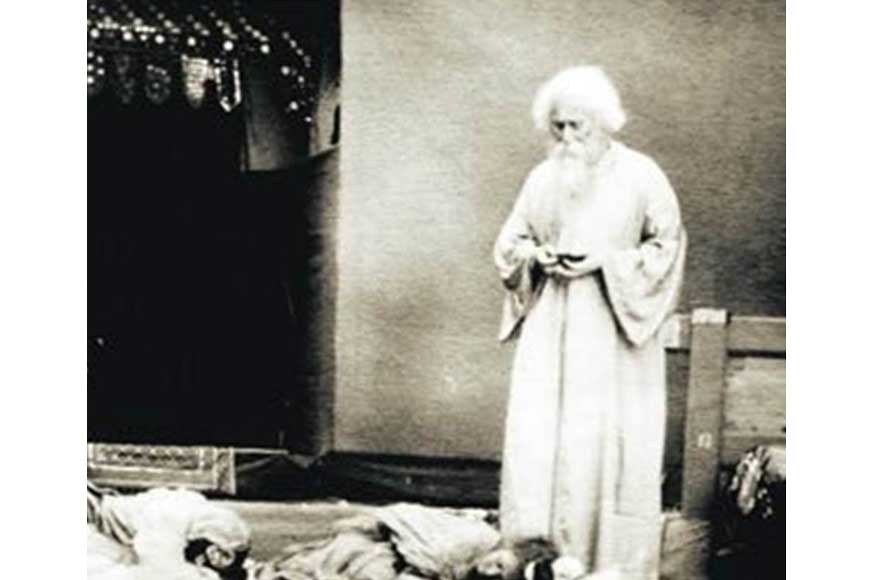

This was followed by another performance at the poet’s Jorasanko residence in Calcutta in order to raise funds for Visva Bharati. This time, Tagore himself played the role of Upala, the play’s sole male character, introduced after the debut performance. The character was created by Tagore because it was felt that young women from Santiniketan performing on a public platform might raise the hackles of the then feudal Bengali society of Calcutta.

The play was again staged at New Empire, Calcutta, in celebration of the poet’s 70th birthday. An impressed B.N. Sircar, founder-proprietor of New Theatres, invited Tagore to direct a film version under the New Theatres banner. The New Theatres Studio played host to Tagore in 1931, and the set was packed with crowds assembled to have a glimpse of the great poet. Tagore directed the film, shot on NT Studio’s Floor Number One. He played the same role and assembled his cast from Santiniketan. The costumes, the jewellery, and the postures harked back to theatre, but that was by Tagore’s personal design.

The shooting of the film also led to the creation of the Gol Ghar within the studio complex, which has a history of its own. The story goes that Sircar, who founded and owned New Theatres, built it overnight before Tagore began shooting Notir Pooja in 1931. “Sircar knew that Tagore would find the studio floor too hot, so he created this cool corner, which later became his own little island of sunshine,” the late filmmaker Arabinda Mukherjee once said.

“Gol Ghar hosted some of the greatest figures in Indian history. Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan, Tagore himself, Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay, Shyamaprasad Mukherjee, and Sarat Chandra Bose are just a few of the personalities who graced New Theatres. From international cinema, the likes of Frank Capra, Jean Renoir and (Vsevolod) Pudovkin graced the studio. Sircar also constructed a theatre called Chitra (later Mitra) as an outlet for films produced by New Theatres,” Mukherjee had said.

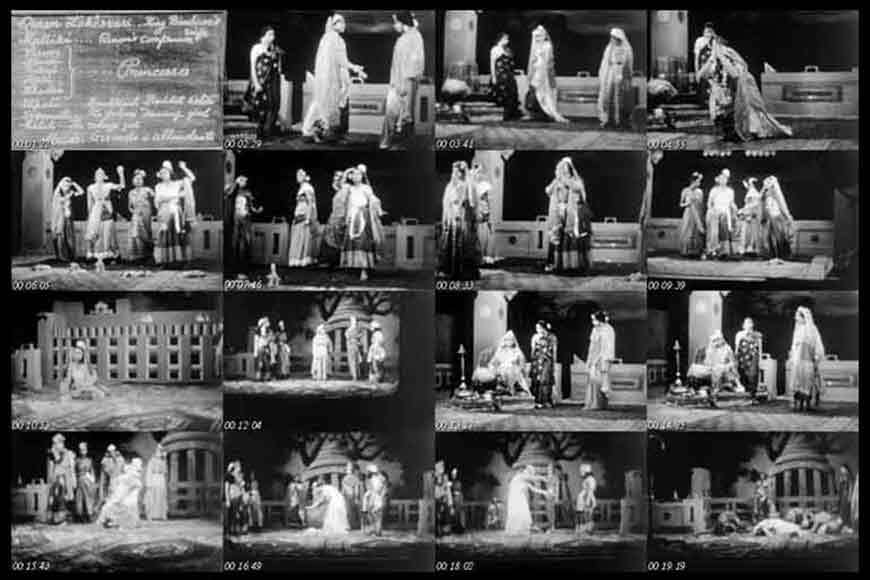

Nitin Bose cinematographed the film and Subodh Mitra edited it. Breaking conventional rules of cinema, Notir Puja was filmed like a stage play. After editing, the footage measured 10,577 feet, and the film was released at Chitra Talkies on March 14, 1932. Sadly, the prints were reportedly destroyed in one of the two devastating fires of 1940 and 1942 at New Theatres.

In Notir Puja, Tagore dramatised the conflict between two faiths – Brahminical Hinduism and Buddhism - and two sets of incompatible values. It is an important milestone in Indian cinema, as it is the only time when Tagore - a writer, poet, musician and painter - interacted closely and directly with another medium. The screenplay was written under his guidance by his nephew Dinendranath Tagore.

Though now lost, portions from the film were found and used in a documentary by NFDC without the original soundtrack, but with a different, newly recorded soundtrack comprising Tagore songs by Hemanta Mukhopadhyay and Suchitra Mitra. The clips now seem grindingly slow, grainy, and hazy. But when one considers the lack of technical infrastructure in cinema at the time, and the fact that these have been restored from the ashes of what remained after many years, one’s perspective changes.