New English translation pays homage to iconic Thakumar Jhuli

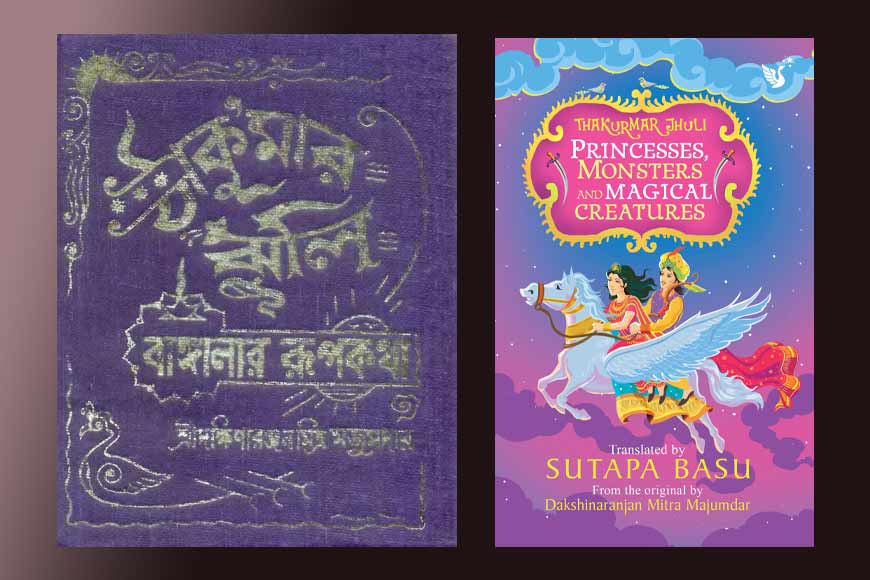

In 1907, Dakshinaranjan Mitra Majumdar (1877-1956) compiled a number of Bengali folk tales and fairy tales he had been listening to since childhood, into a book he called ‘Thakumar Jhuli’ (also referred to as Thakurmar Jhuli). It was quite possibly the first time that the oral storytelling tradition of Bengal was being given written representation for the mass market, and yet, Dakshinaranjan had to struggle to find a publisher, to the point where he decided to self-publish. It was only thanks to the intervention of renowned educationist, folklore researcher, and writer Rai Bahadur Dinesh Chandra Sen that publishers Bhattacharya & Sons agreed to publish Dakshinaranjan’s work. And sold 3,000 copies in the first week of publication.

Sutapa Basu

Sutapa Basu

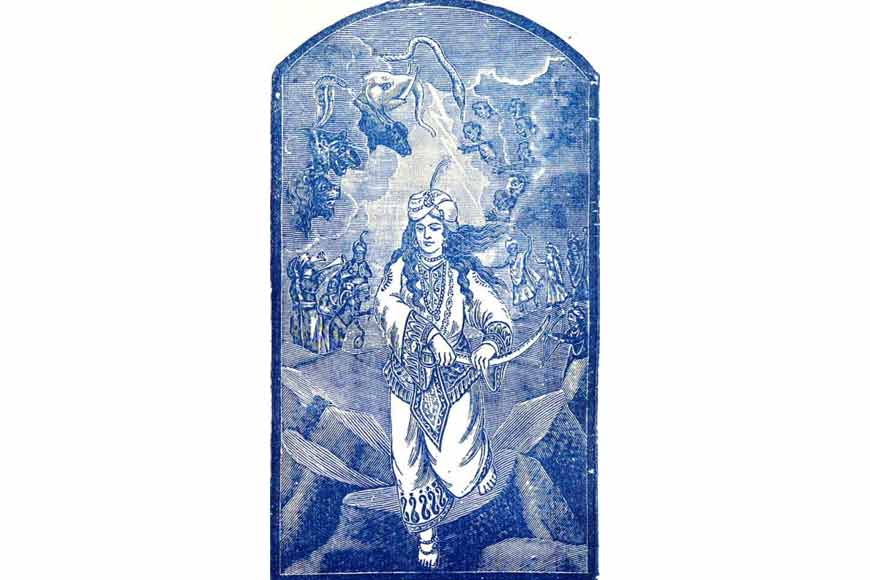

It has simply kept on selling since, though the original publishers are long gone. The book is now copyright-free, which has encouraged many small publishers to come forward with new editions, quite different from the original with its signature blue font and beautiful lithographs. All these editions, however, have been in Bengali, until now. This year, Delhi-based author, translator, and poet Sutapa Basu has published ‘Princesses, Monsters, and Magical Creatures’, an English translation of ‘Thakumar Jhuli’, which she hopes will “make this legacy and heritage available to all”.

More than a century ago, the stupendous success of Thakumar Jhuli not merely vindicated Dakshinaranjan’s belief that there was a market for simple folk tales reproduced faithfully in writing to capture as much of the oral flavour as possible. It also paved the way for generations of Bengali children to revel in the world of Lalkamal-Nilkamal, Buddhu-Bhutum, or Arun-Barun-Kiranmala. The importance that Dakshinaranjan’s contemporaries attached to the book is evident from the fact that no less a personage than Rabindranath Tagore agreed to write a foreword for it.

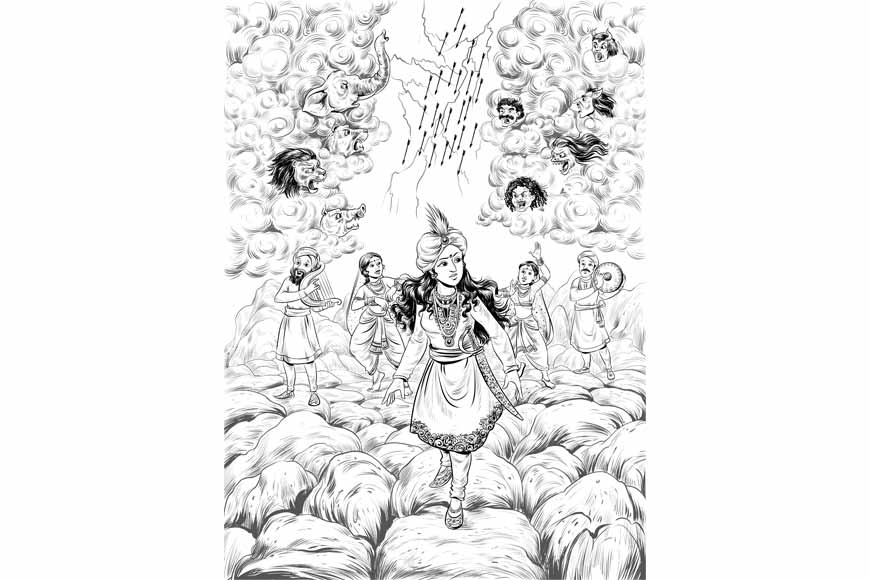

Kiranmala

Kiranmala

Typically going beyond what others saw, Tagore noted that there was an urgent need to revive Bengal’s folk literature if the influence of European fairy tales and their translations was to be countered. Indeed, he declared that these tales would imbibe in children a sense of nationalism at a time when India was struggling to shape its national and cultural identity after two centuries of British rule, that indigenous folk literature would remind people of their rich native oral traditions.

As far as Basu is concerned, that need still exists. “There was an earlier English translation of Thakumar Jhuli (‘Tales My Grandmother Told Me’ by Rina Pritish Nandy in 2005), but it is no longer readily available, and I thought there was a vacuum that needed filling,” she says. “This is not merely a book, it is a piece of our literary legacy which needs to spread far beyond the borders of Bengal, particularly at a time when even many Bengali-speaking children are not entirely comfortable reading in their mother tongue.”

Kiranmala old

Kiranmala old

Regrettable as that may sound, it is indeed a fact that plenty of Bengali children (and quite a few adults too), do not read Bengali easily, for reasons geographical or cultural. Which ought not to mean that they should be deprived of the superb richness of Dakshinaranjan’s timeless anthology. And since Basu has remained faithful to both the narrative structure and voice of the original, her translation ought to go a long way in filling the gap that she speaks of.

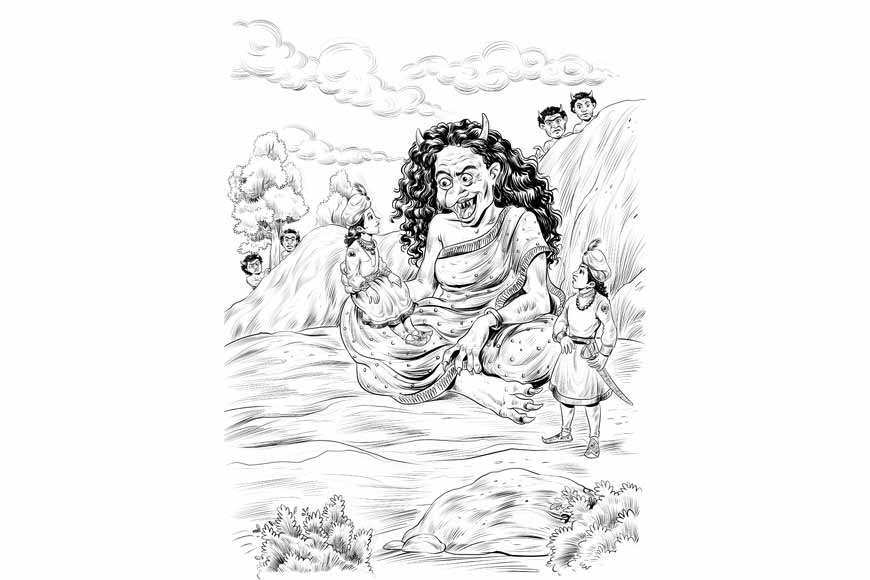

Lalkamal Nilkamal

Lalkamal Nilkamal

Understandably, she has made a few modifications relevant to our times. In her own words, “Often, we are offended by social mores and values without placing them in their proper context. What we see as offensive now would not have been so 100 years ago. For example, my translation attempts to make the misogyny (of the original) palatable by subtly tweaking the text. But the idea of a man having more than one wife, for instance, was prevalent in Indian society as recently as the 1950s.”

With a target group of five to 10-year-olds, Basu feels that the values espoused by the original ‘Thakumar Jhuli’, such as “victory to the righteous and deserving, filial duty, the wisdom and strength of women despite their lower social position, punishment for the wicked, and the fact that wealth alone is not a measure of success or position”, are important to drive home. The feedback she has received from her own grandchildren for ‘Princesses and Monsters…’ convinces her that she is on the right track. “I have tried to spread awareness about how people lived in the past. And heighten the geographical diversity of Bengal by deliberately using various settings for the stories,” she adds.

Sukhu Dukhu

Sukhu Dukhu

The Bengali flavour comes through in words like ‘rakhosh’ (man-eating demon), which Basu has retained instead of the Sanskritised ‘rakshas’, and ‘khokosh’ (a sort of mini rakhosh), as well as ‘byangoma’ and ‘byangomi’, the wise talking birds who often advise and guide the human characters. As she puts it, “In an age when our children are so familiar with the demons and ghosts of the Harry Potter books, for example, I just wanted to show them that all of it has existed in our culture as well, for centuries. All we need to do is rediscover them.”