National Award for Gumnami reflects a distinct pattern

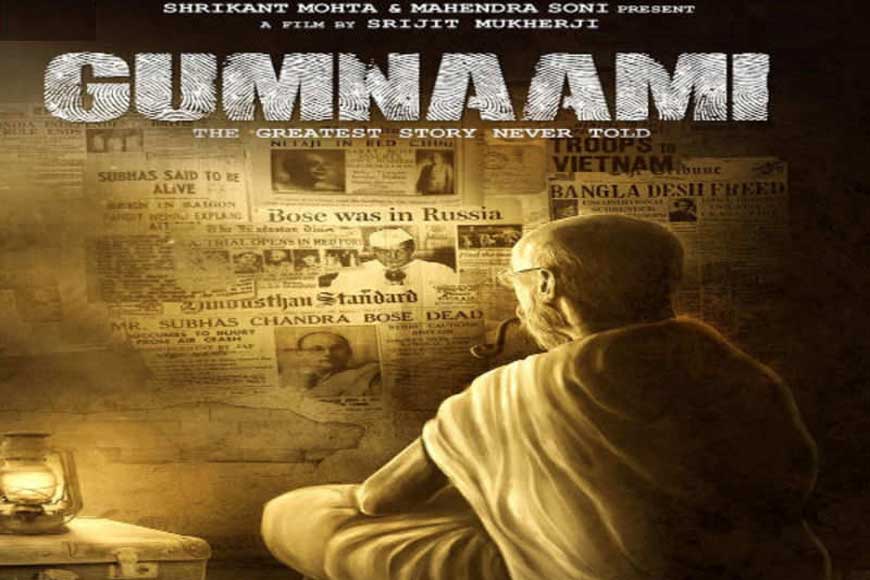

When filmmaker Srijit Mukherjee was scheduled to release his film Gumnami (2019), based on a popular theory that Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose actually survived the plane crash that supposedly killed him, many of Netaji’s descendants were voluble in their protest. In particular, his grand-nephew and eminent historian Sugata Bose called the film “an insult to Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, a travesty of history and a mockery of the arts”.

The first point of difference between awards then and awards now is that, since the lines between mainstream and arthouse cinema have blurred beyond recognition, we have seen the entire concept of National Awards in every language, including Bengali, shifting to mainstream cinema.

Now that the film has won the National Award for Best Bengali Film, Srijit has gone on record to state that his struggle with these very opponents disturbed him a lot, and he felt avenged when the film became a box office hit. Srijit is a good friend, but one does feel like asking – what, then, is more important for the filmmaker, the award or box-office returns? It makes one think.

The first point of difference between awards then and awards now is that, since the lines between mainstream and arthouse cinema have blurred beyond recognition, we have seen the entire concept of National Awards in every language, including Bengali, shifting to mainstream cinema. So what gives? What gives is that today, filmmakers who win awards are thrilled, true, but what thrills them most is the box-office success of the winning films.

The National Film Awards of India were first awarded in 1954, when the government wished to honour excellence in Indian cinema on a national scale. From 1973, the Directorate of Film Festivals began administering the ceremony along with other major events in the country. The first feature film to win the Best Bengali film award was Chhele Kaar (1954) directed by Chitta Bose, a bittersweet film scripted by Jyotirmoy Roy and starring Bikash Roy, Arundhati Devi, Chhabi Biswas and others. Owing to the Covid-19 pandemic, no awards were announced or given away last year, so this year’s awards refer, purportedly, to films censored in 2019.

The Ministry of Information and Broadcasting stipulates that the National Awards aim at encouraging (a) films of aesthetic and technical excellence (b) films with social relevance (c) films that aid the understanding and appreciation of the country’s different cultures and (d) films that abide by the unity and integrity of the nation.

If one were to trace the history of National Awards for Bengali cinema, it would show a list of names which fit perfectly into the first category - films of aesthetic and technical excellence. Were these films, as mentioned in point (b), socially relevant? One is not sure because this was not mentioned in the citations. The opening of windows to every kind of regional cinema fulfilled criterion (c) as winning regional films were viewed first by the jury members and later, when they were screened at the International Film Festival of India in the ‘Indian Panorama’, section, a larger audience could watch them.

Left to Right - Srijit Mukherjee, Kaushik Ganguly, Prabuddha Banerjee, Arjun Gourisaria

Left to Right - Srijit Mukherjee, Kaushik Ganguly, Prabuddha Banerjee, Arjun Gourisaria

Coming back to Bengali cinema, the scenario has changed and so has the definition of ‘aesthetic and technical excellence’. For old-timers who have watched earlier award-winning films, do contemporary Bengali award-winners stand anywhere in comparison to Pather Panchali (1955), Kabuliwala (1957), Sagar Sangamey (1959), Bicharak (1959), Devi (1960), and so on?

Of course, there were ‘hiccups’ then too, such as the year when Asit Sen’s Uttar Phalguni (1963) bagged the Best Bengali Film Award while Tapan Sinha’s brilliant Jatugriha (1964) went with a mere Certificate of Merit. While Khwaja Ahmed Abbas bagged the President’s Gold Medal for Best Film for Shehar Aur Sapna (1963), while Satyajit Ray’s Mahanagar (1963) had to remain content with a Certificate of Merit.

We have observed that there was perhaps a pattern that made itself felt with filmmakers being repeated with award-winning films every year. A friend of mine says that the award for Gumnami is perhaps dictated by political concerns, since it deals with the controversial subject of Netaji’s return in a different avatar. Is the current government at the Centre, purely for electoral reasons, bending backwards to bestow awards on a film that deals with one of its ‘current Bengali heroes’?

Also read : The Kolkata film festival nobody knows about

The focus has certainly shifted more to lavish mounting, location shoots beyond Indian shores, and a blend of actors from theatre, television, and films, while the magic of new technology, the economics of digital filmmaking and the finished, sophisticated ‘look’ of a film redefine ‘excellent aesthetics and technique’. Social agency, too, has taken a backseat to a completely personal take on the narrative such as Anjan Dutt’s Ranjana Ami Aar Ashbona (2011), a personal take by the director on the struggles of a modern, new-age singer, which landed a National Award for Best Feature Film.

Personally, I feel Gumnami as a film began well but ended in great melodrama, not justified by what went before. Towards the end, the script and actor Anirban Bhattacharya who plays the angry journalist Chandrachur go completely haywire when Chandranchur hears that though the Mukherjee Commission has accepted his theory, the government has rejected it.

Just before that, after a night with his ex-wife, he suddenly wakes up and walks around in his underwear while the ‘ghost’ of Netaji as Gumnami speaks to him. Both the surrealism of the scene and the walking about in his underwear are embarrassing and completely out of tune with the rest of the film. And yet Srijit has also bagged the award for Best (Adapted) Screenplay.

Kaushik Ganguly is not a hot favourite with this writer because he is quite inconsistent as a director, though brilliant as an actor. But his film Jyeshthoputro bagged both the Best Screenplay (Original) and the Best Background Music awards, which goes to the very low-key but brilliant music composer Prabuddha Banerjee. Banerjee’s music, played at the procession for the dead father, not to leave out the Tagore song, makes the crowds go berserk when Indrajit begins to sing. Not to forget lines sung from the Internationale as a tribute to the strong and ardent Communist, which the father was, is touching and very appropriate. Banerjee’s award is an extremely deserving one.

If you ask me, though Srijit is a very good friend, I would have chosen Jyeshthoputro over Gumnami because, except the opening frames, the film begins and ends smoothly minus any jerks, narrative-wise and technically as well. Besides, unlike Gumnami, the film conveys an understated social message that underlines the shift in rituals depending on which of the two sons, older or younger, is truly entitled to perform the last rites of a dead father.

Ganguly’s film faced problems with another director accusing him of ‘borrowing’ a script which he (this journalist-turned director) had worked on with the late Rituparno Ghosh. The intelligent Ganguly offered a politically correct answer by calling the film ‘a tribute to Rituparno Ghosh’!

If you ask me, though Srijit is a very good friend, I would have chosen Jyeshthoputro over Gumnami because, except the opening frames, the film begins and ends smoothly minus any jerks, narrative-wise and technically as well. Besides, unlike Gumnami, the film conveys an understated social message that underlines the shift in rituals depending on which of the two sons, older or younger, is truly entitled to perform the last rites of a dead father. The award to Gumnami is perhaps a reflection of the political ideology of the ruling party, which appears hell-bent on reviving historical figures, hence the award to Kangana Ranaut for her performance in Manikarnika.

One must not forget the other awards. One of them is the Best Editing Award to Arjun Gourisaria for Shut Up Sona (Hindi/English) in the non-feature films section and Farha Khatun, who bagged the Best Film on Social Issues award in the non-feature film section for her brilliant film Holy Rights, which portrays a group of Muslim women doing courses on the Quran so that Muslim religious leaders cannot tell them otherwise on rules regarding talaq. She shares her award with another film Ladli (Hindi).

What truly surprises me is that two wonderful films such as Kia and Cosmos directed by Sudipto Roy and Kedara, which marks the directorial debut of composer Indraadip Dasgupta, both released in 2019, do not find even a mention in the awards list, though I have been informed that Kedara did win a Special Jury Award. But neither Robibar nor Bini Sutoye, both directed by Atanu Ghosh, found even a mention in the awards list, though they were highly praised at several film fests.

Perhaps, the very definition of aesthetics in cinema has changed over time and technical brilliance is overshadowed by gizmos and magic, who knows? Change, as the saying goes, is the only thing that remains constant.