Modern Masterpieces: Pratham Pratishruti, Ashapurna Devi’s immortal warrior woman saga

In our times of militant feminism, terms such as battle, war, and fight for equality have become just so much loose change. The world is perhaps no longer willing to remember a small Bengal woman with her quiet smile, whose pen shaped a deeply feminist narrative when the term ‘feminism’ was practically unknown in the land of her birth, beyond a few elite circles.

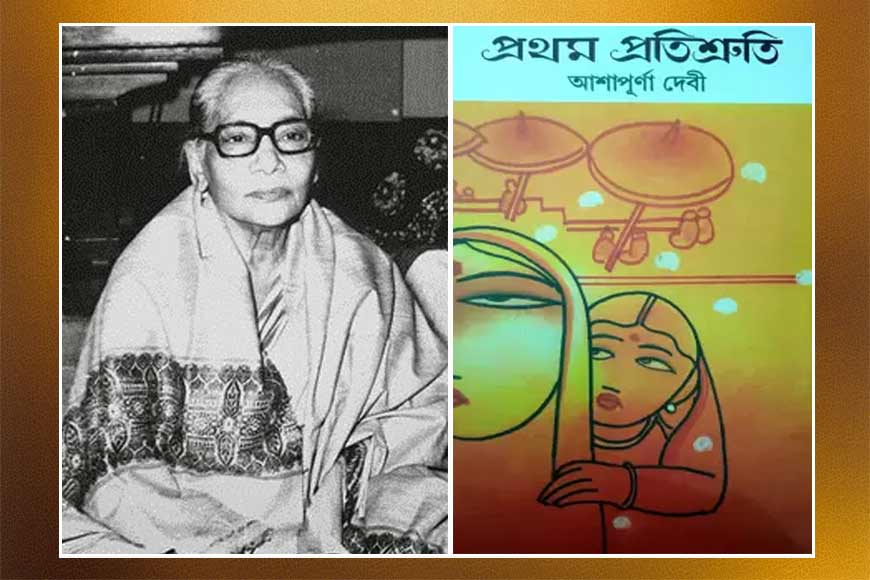

Born in 1909 into a deeply conservative Bengali family, Ashapurna Gupta grew up in an ultra orthodox setting which denied even basic literacy to female members of the household. That a young girl brought up under those circumstances would defy all odds and go on to become one of Bengal’s foremost writers is a triumphal feminist narrative in itself.

Ashapurna was gradually beginning to see around her. As more and more ordinary, middle class women stepped out of the home to study and work, they also became mothers to a more enlightened generation of men. Therefore, the scope of the novel is as sweeping as it is focused, seemingly an impossible combination, and one which resonated with every reader.

Large parts of that journey are reflected in Pratham Pratishruti, arguably Ashapurna’s most celebrated work, the first part of a trilogy which also includes Subarnalata and Bakul Katha. For those who don’t read Bengali, Pratham Pratishruti was translated into English as The First Promise (2004) by Indira Chowdhury, and adapted as a popular 1987 Hindi TV series starring Rameshwari as the protagonist, which some viewers may remember.

Published in 1964, Ashapurna’s magnum opus tells the story of the free-spirited, intelligent, fiercely independent Satyabati, given away in marriage at the age of eight according to prevailing social norms. The plot centres around Satyabati’s lifelong daily struggle against familial control, mental and physical oppression, and quest for answers about the patriarchal society she sees around her, and the toxic family politics that repression can cause.

There is nothing strident or flashy about Ashapurna Devi’s feminism. Even at her most outspoken and rebellious, the young Satyabati is largely unaware that she is challenging centuries-old customs and practices, and much like Ashapurna herself, spends most of her life as a quietly dedicated housewife and mother who wants the best for her children and husband. But every time she steps out of her restrictive circle, she becomes an unstoppable force for change.

Her father, the legendary and wealthy kaviraj (Ayurvedic physician) Ramkali Chatterjee, shapes much of her early thinking and behaviour, indulging her feisty, outgoing character much to the outrage of several widowed relatives in the household, and even his wife. However, Ramkali’s towering personality and imposing physical presence make him an object of fear and reverence among most of his family, with the notable exception of his equally strong-willed daughter.

Satyabati’s freedom of choice and movement before her marriage are starkly juxtaposed against the extremely repressed existence of the other women in the family, single, married or widowed. And against her own post-marriage, when her refusal to toe the societal line leads to furious clashes with her cruel, domineering mother-in-law. Matters come to a head when her husband Nabakumar, who can’t help caring about Satyabati despite his disapproval of her unconventional behaviour, writes to Ramkali asking him to take Satyabati away because he fears for her life.

To everyone’s shock, Satyabati refuses to leave her matrimonial home, because running away from battle is not in her character. Instead, she stays and fights on, finally persuading Nabakumar to move to Calcutta with their two young sons. It is there that she gives birth to her only daughter Subarnalata, who she hopes will carry on her legacy.

The modern education she had dreamed of for her children in Calcutta fails to protect her sons from inheriting the patriarchal mindset, nor does it stop her husband from marrying off Subarnalata at the first possible opportunity. The widening rift between Satyabati and Nabakumar, thanks to her determination to help those whom society sees as ‘fallen’ and his opposition to it, is cemented when he stands by and lets his mother give away his young daughter in marriage. Heartbroken and in mourning, Satyabati leaves her husband and sons to join her father in Benaras.

Satyabati’s freedom of choice and movement before her marriage are starkly juxtaposed against the extremely repressed existence of the other women in the family, single, married or widowed. And against her own post-marriage, when her refusal to toe the societal line leads to furious clashes with her cruel, domineering mother-in-law.

Ashapurna herself was married at 15, though her husband turned out to be as supportive as he could be within the confines of propriety. She knew inside out the agony of growing up as a woman in Bengal of the early 20th century. Pratham Pratishruti is thus as much a social critique as a feminist narrative, as much a story of a blindly superstitious and narrow-minded society as of one individual. It is a society in which women turn against women in order to secure their own positions, where acts of horrifying mental and physical cruelty are perpetrated in the name of culture and conformity.

Satyabati thus becomes a figurehead for all women rebelling against such conformity, which Ashapurna was gradually beginning to see around her. As more and more ordinary, middle class women stepped out of the home to study and work, they also became mothers to a more enlightened generation of men. Therefore, the scope of the novel is as sweeping as it is focused, seemingly an impossible combination, and one which resonated with every reader. It was this worldview that led to a Rabindra Puraskar (1965) and Jnanpith Award (1976) for Ashapurna, though awards held little meaning for her.

Today, she remains one of the bestselling authors in Bengali literature, proving the timelessness and universality of her creations.