Mind matters: How Bengali cinema treats mental health

What do films like Habji Gabji, Hritpindo and Bela Shuru have in common? They all deal with different kinds of mental disorders of which, some are placed with proper research into the issue and the others are just done without much thought but only with entertainment through melodrama for the mass audience in mind.

Bengali cinema has had a good track record in exploring different kinds of mental illness. Yet, one must reconcile to the fact that the borders between who is normal and who is not are rather blurred today because even with modernization, globalization and the women’s movement having made long strides across the world, the social stigma against whatever we consider abnormal, remains and this stigma spills over into Indian cinema of every genre in general and Bengali cinema in particular. Even established directors have either turned the other way in dealing with mental disorders in some characters in their films or have deliberately and with designed intention, abused the said illness and therefore, spread misinformation about mental illness among their audience.

Bengali films dealing with mental illness are generously sprinkled with ignorance about mental illness, abuse of mental illness and even, failure to recognize mental illness when it happens in any character in a given film and suggest an absurd, almost comic solution to the problem to bring the story to its anticipated happy ending. Very few films suggest medical strategies to resolve the mental issue. They use mental illness as (a) a dramatic device, (b) highly emotional melodrama, (c) an additional commercial strategy to add to the entertainment value of the film.

Hritpindo for example, running in the theatre right now, deals with a young, married woman who, as the result of a very bad accident followed by brain surgery, goes back to being 14 years old and forgets the years beyond her 14 years. But she looks, talks and behaves like a girl of seven or eight, talks in almost a lisp and demands attention from her father and husband like an eight-year-old would. She recognises her father because he has been a part of her girlhood. But she cannot reccognise her husband because he came into her life during the ten or twelve years erased from her life and this is when she got married. If it was a brain surgery, why in God’s name the film is called Hritpindo, which means “heart”? Though Arpita Chatterjee as the affected woman acts well, the film, directed by Shieladityo Moulik, falls flat on its face for the misrepresentation of the mental disorder she is suffering from.

Habji Gabji, directed by hotshot director Raj Chakraborty who is an ace at producing commercial hits, this time, has taken on the serious issue of Internet Gaming Addiction Disorder and what it can do to small children who get addicted to the cell phone often given to them by very busy parents who have little time to spend with their children. The child, usually an only one, is lonely and plays with himself at home when his parents are away at work. A large number of adults and teenagers all over the world are highly addicted to gaming. Conventionally, we connect addictions with substances such as alcohol and drugs but with the increased use of technology, our regular routine addictions to the internet, smartphone and gaming are becoming common. Habji Gabji focuses on the impact of the gaming addiction in a mall boy of a nuclear family and how he creates and begins to live in an alternate, fictitious world through his game failing to accept the least parental control

However, what Habji Gabji misses out on is that the problem and its impact takes more space and significance in the film than possible solutions, preventive measures and cures. Pune-based psychiatrist Soumitra Pathare, director of The Centre for Mental Health Law and Policy and one of the authors of the recent Mental Healthcare Act says that the Hindi film industry is “probably three to four decades behind Hollywood” when it comes to scripts dealing with mental health.” (Sachin Kalbag, The Hindu, January 13, 2018.)

Bela Shuru directed by the very successful directorial pair Shiboprosad Mukherjee and Nandita Roy who always include an agenda in their films, this time deals with Alzheimers’ in the wife of an old couple married for 50 years where the wife gradually degenerates completely into loss of memory. But as the film goes along with its leading couple, played by Soumitra Chatterjee and Swatilekha Sengupta, we get to see that the wife gradually degenerates into complete lunacy. She smears her face with vermillion, the grown-up children with problems of their own try their best to help both parents but when everything else fails, they go away leaving their father to play ludo with his wife. The film stays true to the medical truth that Alzheimer’s has absolutely no treatment but the way her loss of memory is depicted has more significant symptoms of lunacy than loss of memory. The film is drawing packed theatres mainly because both the old couple who acted are no more. The film is not only loud but is spilling over with a lot of melodrama which of course, is the signature of Nandita Roy and Shibaprasad Mukherjee’s trademark. And to think that their debut film Icche, brilliantly explored the problems of a boy whose mother is so fixated on him that she almost destroys his life, his love, his aspirations and so on till he gathers courage to walk out of her life.

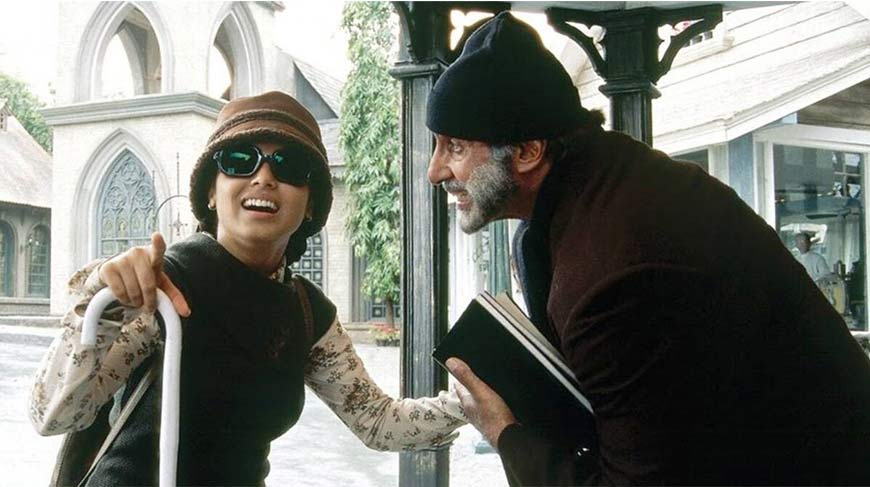

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia. There is no cure for the disease which worsens as it progresses, and eventually leads to death. But in Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Black, the climax hinted that Debraj Sahai (Amitabh Bachchan) who drifted steadily and surely to a severe case of Alzheimers, was on the verge of regaining his power of speech that he had lost. This is medically impossible.

Dr. Van Velsen, who produced the results of her research for World Mental Health Day on October 9, 1998, says: "In a lot of the films there is the underlying message that all the patient really needs is love and affection. There is a tendency in films to try and normalize mental illness by saying that patients don't need treatment, they need love. The audience gets the two extremes and what we are not getting are portrayals of people with chronic illness."

However, Bengali cinema has had its share of very good films dealing with mental illness. One of them is Deep Jele Jai (1959) which is set inside a mental home in Kolkata and the nurse, Radha, trained in England, falls in love with a patient she is entrusted with. Deep Jele Jai has survived the onslaughts of time, technology and evolution to remain one of the best films directed by Asit Sen marking Suchitra Sen in one of her unforgettable performances in a heroine-oriented film.

Hrad (1955) a film based on an excellent novel by Bimal Kar, potrayed Uttam Kumar in a mental asylum where he has forgotten slices of his life and behaves in a way that make people feel he is mad. The doctor however, does not agree and treats him with gentle kindness. However, the novel was better than the film. In Ami Shey O Shokha, a triangular love story, Uttam Kumar, in a double role as the hero’s brother, lands up first in prison and then becomes mad because a student who fell in love with him and was spurned, complained of being molested which made the innocent man labelled as a criminal. But this was just a sub-plot and not the main story.

Prof. Dinesh Bhugra's Mad Tales of Bollywood is an exhaustive study of the representation of mental disorder in Hindi cinema. Among other works are Psychoanalysis and Film and Psychiatry and the Cinema by Prof. Glen Gabbard.

If films and the media can reinforce and perpetuate stereotypes and misinformation about schizophrenia or serious mental illness, then it is the duty of the media to correct this misinformation to facilitate empathy. And people involved with media should be alert to the potential that they have.